In an era where fast internet speeds are essential for daily activities, a new study highlights just how much slower human brains are in processing information compared to the internet, the New York Times reports.

While many people are familiar with the frustration of a slow web connection, a team of researchers has now quantified the speed at which the human brain processes data. Their findings show that, when it comes to information flow, the human brain operates at a mere 10 bits per second (bps), a rate far behind the data speeds of modern technology.

The study, titled “The Unbearable Slowness of Being”, was published in the journal Neuron this month and offers an interesting perspective on the complexities of the human brain. Markus Meister, a neuroscientist at the California Institute of Technology and one of the study’s authors, explained that the findings serve as a counterbalance to the often exaggerated claims about the brain’s extraordinary processing capabilities.

“If you actually try to put numbers to it, we are incredibly slow,” he remarked.

Dr. Meister’s interest in this topic began while teaching an introductory neuroscience class. He realized that while much was known about the brain’s structure and function, no one had yet quantified the speed at which information flows through it. To estimate this flow, Dr. Meister and his graduate student, Jieyu Zheng, analyzed common tasks like typing and gaming, both of which require quick processing and coordination between the brain and body.

For example, typing speeds can give insights into how much information is processed by the brain. In a 2018 study, researchers found that the average person types 51 words per minute, with some skilled typists reaching speeds of up to 120 words per minute. By applying information theory, Dr. Meister and Ms. Zheng calculated that typing at this speed requires an information flow of about 10 bps. Despite the rapid finger movements of gamers, they too exhibited the same rate of 10 bps, as they have fewer options to choose from than typists.

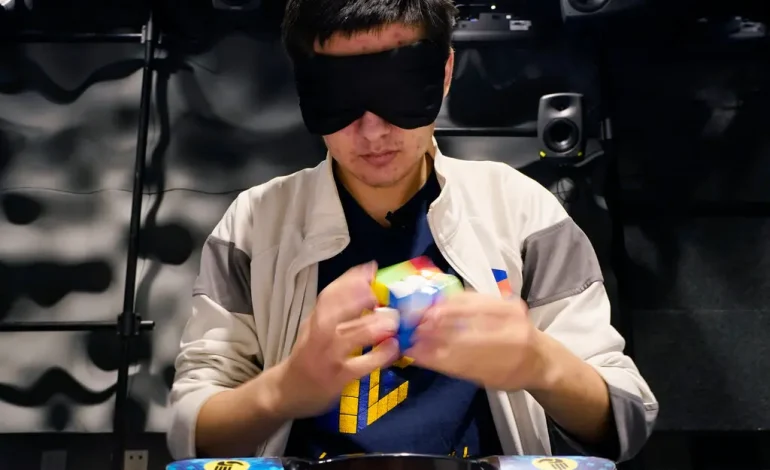

The researchers also looked at more complex mental tasks that do not rely on physical movement. For example, they examined “blind speedcubing,” where participants solve a Rubik’s Cube while blindfolded. In a 2023 competition, American speedcuber Tommy Cherry spent just 5.5 seconds inspecting the cube before solving it. Dr. Meister and Ms. Zheng calculated that Cherry’s information flow during the inspection phase was only 11.8 bps. Similarly, in a memory sport known as the “5 Minute Binary,” players memorize long strings of binary numbers, and the world record holder, Munkhshur Narmandakh, was estimated to have processed just 4.9 bps while memorizing thousands of numbers.

In contrast to the slow processing speed of the human brain, sensory information enters the body at an incredibly high rate. For instance, the millions of photoreceptor cells in a single human eye transmit approximately 1.6 billion bits per second, which means that the brain only processes a tiny fraction of the information it receives from the senses.

Dr. Meister and Ms. Zheng suggest that this disparity—between the massive amount of data our senses receive and the limited amount we process—poses an intriguing question for psychological science. They argue that further research is needed to explore why the brain only processes such a small fraction of the information it encounters.

While some experts, such as Britton Sauerbrei, a neuroscientist at Case Western Reserve University, have raised concerns that the study may not account for unconscious signals—such as those involved in standing, walking, or maintaining balance—Dr. Sauerbrei also agreed with the study’s conclusions about conscious tasks.

“I think their argument is pretty airtight,” he said.

The findings also encourage researchers to consider how the information flow in the human brain compares to other species. Dr. Martin Wiener, a neuroscientist at George Mason University, noted that such comparisons might reveal significant differences in the information processing capabilities of various animals, particularly those with faster reflexes or sensory responses, such as flying insects.

The latest news in your social feeds

Subscribe to our social media platforms to stay tuned