Blood types—such as A positive, O negative, and AB positive—are more than just classifications for transfusions; they represent genetic adaptations shaped by ancient human encounters with pathogens, Science reports.

A recent study published in Scientific Reports explores the evolution of these blood groups in early modern humans and Neanderthals, revealing how migration and interbreeding influenced their development.

Blood groups, determined by immune proteins on red blood cells, reflect evolutionary responses to diseases encountered by ancient populations. For instance, individuals with type O blood are more susceptible to severe cholera but show resistance to malaria. While humans possess 47 known blood groups, many of their origins remain unclear.

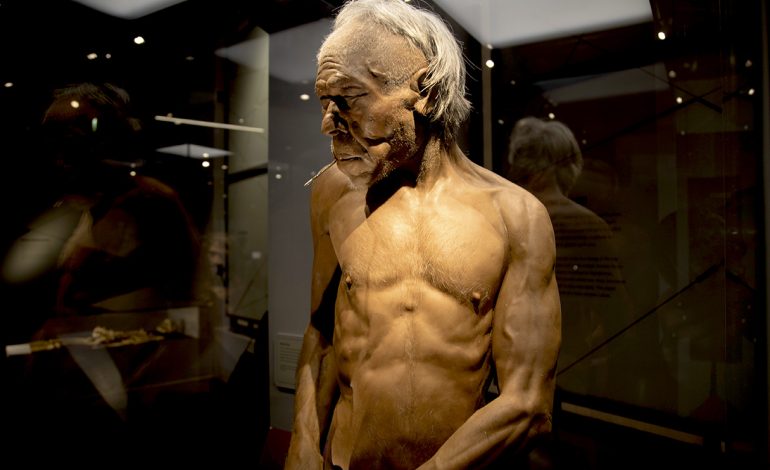

To shed light on this, Stéphane Mazières, a genetic anthropologist at Aix-Marseille University, analyzed ancient genomes from 22 Homo sapiens individuals who lived between 46,000 and 16,500 years ago, 14 Neanderthals who existed 120,000 to 40,000 years ago, and a hybrid individual from about 98,000 years ago. These samples came from sites across Eurasia, including modern-day Germany, Siberia, and China.

The findings reveal stark differences between the genetic histories of Neanderthals and modern humans. Neanderthal blood groups showed minimal variation over 80,000 years, likely reflecting their small, genetically homogenous populations. In contrast, Homo sapiens exhibited rapid genetic changes after leaving Africa approximately 70,000–45,000 years ago.

During their migration, early humans paused for about 15,000 years on the Persian Plateau, a period that likely acted as a “genetic incubator,” allowing new blood type variants to emerge. As populations moved into Eurasia, exposure to diverse pathogens drove the selection of region-specific blood group adaptations.

The study also highlights interbreeding between Homo sapiens and Neanderthals, which introduced a rare blood group variant known as RHD DIII type 4. This variant, now found in some modern populations, may have provided survival advantages in new environments. However, it also has modern medical implications, such as its association with life-threatening conditions in newborns if their blood type is incompatible with their mother’s.

Interestingly, some ancient blood group variants have vanished entirely. For example, the genome of a 45,000-year-old Siberian individual, known as Ust’-Ishim, contained three variants no longer found in humans today. These findings suggest that certain lineages, including Ust’-Ishim’s, were evolutionary “dead ends.”

The latest news in your social feeds

Subscribe to our social media platforms to stay tuned