A new study suggests that microscopic plastic particles may play a role in the development of cardiovascular disease, after researchers found significantly elevated levels of microplastics and nanoplastics in the arterial plaque of individuals who had experienced strokes or vision loss, Business Insider reports.

The research, presented this week at the American Heart Association’s meeting in Baltimore, examined the carotid arteries of 48 individuals, a major blood vessel that supplies the brain with oxygen-rich blood. The findings revealed that plaques from patients who had experienced strokes or other symptoms contained up to 51 times more plastic than those from asymptomatic individuals.

“There is some microplastic present in healthy arteries,” said Dr. Ross Clark, a vascular surgeon at the University of New Mexico and the study’s lead researcher. “But the amount that’s there when they become diseased — and become diseased with symptoms — is really, really different.”

While microplastics and nanoplastics — tiny fragments shed from plastic products — have previously been found in organs like the lungs and liver, their presence in blood vessels and potential connection to vascular disease is a relatively new area of inquiry.

The study builds on earlier research that linked microplastics in arterial plaque to an increased risk of heart attacks, strokes, and even death. This latest work suggests that these plastics may not only be present in diseased arteries but could also influence how those diseases progress.

Cells in plastic-rich plaques displayed unusual patterns of gene activity. Specifically, immune cells in these plaques had turned off a gene involved in controlling inflammation. Other changes were found in stem cells associated with stabilizing plaque and preventing cardiovascular events. These genetic shifts raise questions about whether plastic exposure could contribute to disease by disrupting the body’s immune response or healing mechanisms.

“Could it be that microplastics are somehow altering their gene expression?” Clark asked. “It gives us a hint as to where to look, but we need much more research.”

Experts in the field agree that the findings are intriguing.

“It’s very shocking to see 51 times higher [plastic levels],” said Dr. Jaime Ross, a neuroscientist at the University of Rhode Island who was not involved in the study. “In my work, three times is considered a strong signal. This is very striking.”

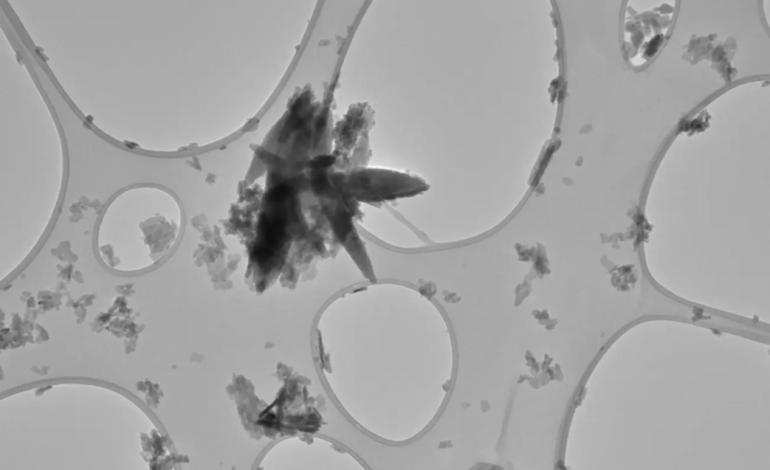

However, the study has not yet been peer-reviewed, and Clark acknowledges its limitations. One challenge is accurately measuring plastic levels in human tissue. To isolate microplastics, the researchers vaporized plaque samples at high temperatures and analyzed the resulting organic molecules — a method that must carefully distinguish plastics from naturally occurring compounds like lipids.

Clark emphasized that his team took steps to control for potential contamination and improve accuracy, but he acknowledges that the technology is still evolving. He plans to replicate the findings and submit the study for peer-reviewed publication later this year.

This research adds to a growing body of evidence that tiny plastic particles are not just widespread in the environment but are accumulating in the human body in ways scientists are only beginning to understand.

“Almost all of what we know about microplastics in the human body, no matter where you look, can be summed up as: It’s there, and we need to study further as to what it’s doing, if anything,” Clark said.

The latest news in your social feeds

Subscribe to our social media platforms to stay tuned