EXCLUSIVE: Screwworm Resurgence in Mexico Raises Alarm — What to Expect

A parasitic fly that was once considered eradicated from the United States has re-emerged as a pressing threat. The New World Screwworm (NWS), infamous for its flesh-eating larvae, is spreading northward in Mexico — prompting the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) to suspend live cattle, horse, and bison imports across the southern border.

“This cannot happen again,” warned USDA Secretary Brooke Rollins in a recent statement on X, referencing the decades-long economic damage from the last screwworm outbreak, which ended in 1966 after an extensive eradication effort.

To better understand the science, risks, and containment strategies surrounding this alarming development, Wyoming Star (WS) spoke with Maxwell Scott, Professor in the Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology at North Carolina State University, whose research has touched on cutting-edge control methods for screwworm and its close relatives.

WS: What are the main factors contributing to the recent resurgence of the New World Screwworm in Mexico, particularly its northward spread?

It is not clear why the barrier failed after so many years of successfully keeping screwworm out of Panama. Perhaps the strain used (called Jamaica 06) was losing effectiveness in the field, although it was passing QC [quality control] tests in the plant. The program has now replaced the J06 strain with a new strain that is derived from outbreak flies. The program has replaced the strain used many times over the past 60+ years.

The illegal movement of people across the border with Colombia may have contributed… if infested animals were being moved with the people.

WS: To what extent has illegal cattle trafficking influenced the spread of the screwworm, and what measures could mitigate this issue?

From a talk I heard at the ESA meeting last November, it is clear that movement of infested livestock within Central America contributed to the rapid spread. Very unlikely the fly could have made the large jumps that were observed by itself. It was a talk by someone from APHIS.

WS: How effective are current containment efforts, such as the release of sterile flies, in preventing the spread of the screwworm into the United States?

The sterile flies are effective. In the eradication campaign in Mexico in the past, the plant produced 500 million sterile screwworms per week. The plant in Panama is about 100–120 million per week.

Hopefully, that will be enough to contain the fly in Mexico.

WS: What is the likelihood of the screwworm establishing itself in U.S. livestock populations, and what would be the potential economic and ecological impacts?

Hard to know at this time. Hopefully the fly can be stopped in southern Mexico. The IAEA estimates losses in South America are about $3.6 billion annually. The estimate of annual cost to the USA would be about $900 million.

WS:: What long-term strategies would you recommend to prevent future outbreaks and ensure the screwworm remains eradicated in the U.S.?

There are potentially more efficient genetic control strategies that could be used to control screwworm than releasing sterile males and sterile females, as has been done since the 1950s. With USDA-ARS scientists, we have made strains that produce only males. Releasing sterile males is more effective, as females don’t contribute to genetic suppression, and sterile males that mate with the co-released sterile females do not contribute to suppression. There are various fertile male release strategies that could be developed. Perhaps the most exciting is CRISPR/Cas9 gene drive, as is being developed to control mosquito malaria vectors in Africa. We are collaborating with scientists in Uruguay to develop gene drive.

There is also a need for more effective traps, which is underpinned by basic research on chemosensory proteins female flies are using to detect hosts. I currently don’t have funding to work on screwworm. We have some funding from NSF to work on chemosensory genes in blow flies (close relatives of screwworm). But that is ending very soon. A small part of a grant from the NIFA BRAG program is on gene drive in secondary screwworm… the closest relative of screwworm that is native to NC.

There is no opportunity to apply for funding at this time.

A Renewed Threat, A Race Against Time

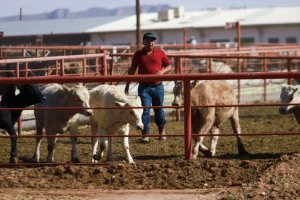

Source: Anadolu via Getty Images

The New World Screwworm, known scientifically as Cochliomyia hominivorax, once caused widespread devastation in the U.S., costing livestock producers millions in losses each year. Eradicated in 1966 through the landmark Sterile Insect Technique (SIT), it reappeared briefly in Florida in 2016 but was quickly contained.

Now, with infested livestock moving across Central America and a reduction in sterile fly production capacity, the risk of a new U.S. outbreak is growing.

The stakes are high: besides animal suffering and economic loss, humans are also at risk, especially in rural border areas. Open wounds, even as small as a tick bite, can invite infestation.

It is increasingly evident that stopping the screwworm from reentering U.S. territory will require renewed innovation, strengthened cross-border cooperation, and sustained funding — all critical to preserving decades of progress in public health and agriculture.

The latest news in your social feeds

Subscribe to our social media platforms to stay tuned