Jewish settlers in the West Bank occupy a central, contentious role in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and Israel’s broader strategy in the Middle East. While they make up a minority of Israel’s population, their presence in the occupied territories has profound implications for diplomacy, security, and the future of any negotiated peace.

The West Bank, including East Jerusalem, has been under Israeli occupation since the 1967 Six-Day War. Though Israel withdrew from Gaza in 2005, it has maintained military control over the West Bank. The area is referred to by many Israelis as Judea and Samaria, reflecting its biblical significance. However, under international law, including the Geneva Conventions, the West Bank is considered occupied territory, and the settlements are regarded as illegal by most of the international community.

In 2023, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) opened proceedings to assess the legality of Israel’s prolonged occupation. Israel disputes the classification of the territory as occupied and claims historical and religious rights to the land, citing continuous Jewish presence throughout history.

There are now more than 700,000 Israeli settlers living in the West Bank and East Jerusalem. Settlements range from small outposts to fully developed towns and cities with infrastructure often inaccessible to Palestinians.

Since the Hamas-led attack on Israel on October 7, 2023, and the subsequent Gaza War, tensions have escalated dramatically in the West Bank. Reports by human rights organizations such as B’Tselem, as well as investigations by Al Jazeera, document a sharp rise in settler violence. Between October 7, 2023, and early 2025, more than 1,800 settler attacks were reported, targeting Palestinian homes, farms, and communities.

This violence, often carried out with limited intervention by the Israeli military, has contributed to displacement, fear, and further instability. Human rights groups argue that the growing impunity of settlers reflects a broader policy of de facto annexation aimed at eroding Palestinian presence in strategic areas.

Moreover, the Israeli human rights group Yesh Din and others argue that settler violence is not just individual lawlessness but an extension of state policy. These incidents often occur in areas where new settlements or outposts are being established, leading to accusations of coordinated displacement of Palestinian communities.

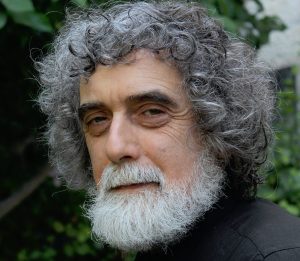

To gain a better understanding of the Israeli settlers phenomenon, Wyoming Star spoke with Gershom Gorenberg, an American-born Israeli journalist and historian specializing in Middle Eastern politics and the interaction of religion and politics. Gorenberg has written a number of books on the subject, such as “The Unmaking of Israel,” “The Accidental Empire: Israel and the Birth of the Settlements, 1967-1977,” and “The End of Days: Fundamentalism and the Struggle for the Temple Mount.”

Wyoming Star: I want to begin with the historic outlook. Let’s establish a timeline of the settlement creation. When were the first settlements created, and what was their purpose?

Gershom Gorenberg: What’s normally referred to as the settlement enterprise began in 1967 after what’s known as the Six-Day War in June 1967, when Israel conquered the West Bank, the Gaza Strip, the Sinai Peninsula, and the Golan Heights. The line between Israel and the occupied territories is normally known as the Green Line because that’s the color in which the armistice line of 1949 was marked on maps. So when we’re referring to the occupied territories, we often refer to what’s beyond the Green Line.

The first settlement beyond the Green Line was established in the Golan Heights in July of 1967, that is to say, a little more than a month after the end of the war. The first settlement in the West Bank was established at the end of September 1967 at a place known as Kfar Etzion.

Kfar Etzion had been a Jewish kibbutz before the 1948 Israeli War of Independence. The area was conquered in May of 1948 by Arab forces, and the settlement ceased to exist. Most of the defenders were killed. There was a push to reestablish a kibbutz in that spot. That was the first settlement established in the West Bank at the beginning of the settlement enterprise. Subsequently, settlements were also established in the Gaza Strip and in the Sinai Peninsula. The ones in the Sinai Peninsula were evacuated as part of the 1979 peace treaty with Egypt, and the ones in the Gaza Strip were evacuated in 2005 under then Prime Minister Ariel Sharon’s disengagement plan, in which Israel withdrew its military forces and ended settlements in the Gaza Strip. The settlement enterprise in the West Bank, on the other hand, has continued to grow since then.

Wyoming Star: What is the political and economic purpose of these settlements?

Gershom Gorenberg: The difficulty I have in answering some of these questions is that after covering this subject for 40 years and writing two books on the subject, boiling this down into a few sentences is very difficult. We can see a variety of reasons for why the settlements have been established. One set of reasons has to do with security claims. The claim that the settlements would change Israel’s borders in any future peace agreement, and the claim that was made by the proponents and continues to be made by its proponents that the pre-1967 borders were too vulnerable and that by establishing settlements in occupied territory, Israel was indicating that there was land that it would not give up in a peace agreement and therefore would establish more secure borders. There were what could be called historical nationalist claims, which are that the territory involved, particularly speaking of the West Bank, was part of the historic Jewish homeland and that Israel had a right to hold that land in the future. I’m stressing here that you’re asking me what the arguments of the advocates of settlement were. I’m not speaking here of my personal views, quite the contrary, I’m explaining to you as a historian and as a journalist what the arguments were that were made.

Wyoming Star: Is this the idea of Greater Israel?

Gershom Gorenberg: Well, yeah, the expression that they use is not Greater Israel; it’s “the whole land of Israel.” It’s what’s known in wider political context beyond Israel. But on a global level it’s known as irredentism: “This is part of our historic homeland, and therefore it should be part of our state.” You can see political conflicts all over the world that are based on these claims. And then there is also a religious nationalist claim, which for a significant part of the settlers is a very basic claim that this is part of the homeland, which not only on a national level but on a theological level belongs to the Jewish people, and that settling this land is an expression of a way of carrying out this religious belief. Now all of those factors figured in various ways in settlement policy to varying degrees depending on what government was in power.

The religious national settlement movement has been particularly influential but is certainly not the only strand of the settlement effort. I will stress that throughout this project, from the beginning, there have been opponents to it within Israel. That opposition has grown over the years.

A strong political stream in Israel says that in order for Israel to remain a democratic state and a state with a Jewish majority and to reach peace with its neighbors, it needs to give up some or all the territories occupied since 1967 and regards the settlements as the impediment to reaching or one of the major impediments to reaching a peace agreement. The point at which that perspective had the strongest influence on policy was clearly in the peace agreement with Egypt, in which Israel in fact gave up the territory that it conquered in 1967 and reached a full peace agreement with Egypt, and in order to do so had to evacuate the settlements that it had established in the Sinai.

Wyoming Star: What is the economic point of the settlements existing?

Gershom Gorenberg: The settlements are not a profitable enterprise for Israel. In fact, they have to be subsidized greatly by the government. To what extent is very difficult to say because there’s never been a single settlement budget in the Israeli budget. The subsidies and incentives that the Israeli government has provided for the settlements are scattered through the budgets of various ministries. So efforts have been made over the years to pinpoint what the overall cost in any given year or in total is. How much has Israel spent on subsidizing this effort? I don’t know of any single figure for a particular year or, more so, in total, but it’s been a very expensive business. It also imposes a price through the defense budget because part of what the Israeli military does is it provides security for the settlements and occupied territory. But in a shifting pattern over the years, there have been all sorts of other ways in which settlements are essentially subsidized by the government. And that’s been an ongoing point of controversy within Israeli politics. This is not colonization for economic purposes. It’s not a profit-making enterprise for the state of Israel. In the view of its advocates, it serves the other purposes to which I’ve already spoken. And in order to make that workable, the government has subsidized it. For instance, housing to various extents and at various times has been cheaper in settlements in the occupied territories than in Israel proper, which created an incentive for Israelis to move to settlements in order to get better housing conditions. And that has been a product of government incentives.

Wyoming Star: So the settlements have been unsustainable from the very beginning? But what’s the incentive for a person to become a settler? The cheaper housing, and that’s it?

Gershom Gorenberg: It depends on the person that you’re speaking of, and the motives can be multiple. My general assumption in dealing with people is that they usually have more than one motivation for what they do. So one has to be careful in analyzing this. But there are certainly people who move to settlements for ideological reasons, whether they see it in secular nationalist terms as part of the Jewish homeland and they want to make sure that Israel holds on to that land or for religious nationalist reasons or, potentially, because they agree with the security argument and they believe that they’re contributing to Israeli security or a combination of all those things. In addition to that, the largest settlements, in fact, are closest to the Green Line, to the pre-1967 border, and have essentially been built as suburbs of Israeli cities, but ones in which housing is less expensive than it is in Israel proper. And many people have moved to those settlements in pursuit of what’s known as quality of life, and these settlements are also often known as “quality of life settlements.”

In principle somebody who ideologically opposes the existence of the settlement is not going to move there for better housing. But the reality is that not everybody is intensely political. I can’t possibly give you a breakdown, but many people have moved to such settlements really out of personal economic reasons. “We can afford an apartment in the settlement of Ma’ale Adumim, and we can’t afford an apartment in the big city of Jerusalem, so we moved to the suburb, which just happens to be a settlement.”

The reality is that normally once somebody does that, obviously they’re going to be an advocate of keeping the settlements, so they’re going to be more likely to vote for those political parties that are in favor of holding on to the settlements than ones that would advocate giving up the settlements for a peace agreement. But in that case, what you’re seeing is the personal economic motives preceding and shaping the political ones. That’s very complicated. When you speak to an individual, it can be a mix of all these things, and it’s hard to determine which came first. The chicken or the egg issue.

Wyoming Star: You’ve mentioned the political opposition to the settlements, but what’s the public perception of them by the Israeli society as a whole?

Gershom Gorenberg: I have often been confronted with the question of what the Israelis think about something, and I’ve never met the Israelis; I’ve only met Israelis. The political perceptions of the settlements depend on where people stand across the extremely wide Israeli political spectrum. There are people who live inside of Israel proper but are avid advocates of the settlement enterprise and see the people living there as patriots doing the best thing for Israel, and there are people who see the settlements as a wasteful, destructive standing in the way of peace who see the pro-settlement parties as damaging to Israel. Since 1967 the future of the occupied territories has become the central dividing issue in Israeli politics. Largely what’s defined as left and right. In other words, if you had come to Israel in 1965, left and right would have been defined pretty much as they were in Europe at the time. On the left side of the spectrum, you would’ve found the socialists and the social democrats, and on the right side of the spectrum, the economic liberals and free marketeers all the way to the hardline nationalists. After 1967, in a gradual process, the political map realigned itself very much around the issue of “Are you in favor of giving up territory for peace, or are you in favor of holding on to the territories?” So where you stand on that spectrum obviously will also indicate where you stand on the settlements.

Wyoming Star: In the current political climate, what’s the most realistic decision for the settlements? Will Israel keep them, or is it willing to give them away?

Gershom Gorenberg: I have another very basic journalistic rule or historian’s rule, which is that I never report the future. It’s difficult enough to report the present and the past. And I will add that all of the important events that I have seen happen in Israel, as in the rest of the world, the really decisive events have defied the expectations of all experts. I would just tell you on a world scale to go look for experts that predicted the collapse of the Soviet Union; the number probably is less than the number of people participating in this conversation right now. But that shaped the entire world that we live in. I remember the night that it was announced on the radio that the President of Egypt, Muhammad Anwar es-Sadat, was going to come to Israel in two days to talk about peace. And I can only tell you that Orson Welles’ broadcast in which he announced that Martians were landing was probably less surprising than the announcement that Anwar Sadat was coming to Israel. And on the negative side of it, as you are, I’m sure, well aware, Israel was taken completely by surprise by the Hamas attack, invasion, and atrocities of October 7th. And all of those things are part of the fabric of events that affect what the future of the settlements will be. So it would be foolish of me to make any predictions about their future.

Wyoming Star: I wanted to touch a little bit on the settler violence. It’s been all over the news, especially since October 7th. With the last high-profile case being an attack on Hamdan Ballal, the co-director of “No Other Land,” an Oscar-winning documentary.

Gershom Gorenberg: There is a serious problem that portions of the settlement population, particularly the ideological extremists among them, have been engaged in continued violence against the Palestinian population. Which is criminal behavior in itself and inflames the situation. It increases the conflict and overall is a major threat to the security of both Palestinians and Israelis because by inflaming the conflict, you’re also threatening Israeli security. A responsible government would be doing everything it could to prevent this and to bring the perpetrators to justice. Unfortunately, the current Israeli government is not behaving in any responsible fashion in that regard. That is in part a product of a longstanding problem—a problem that goes back decades of insufficient law enforcement against the settlers, in part because of an ongoing problem of who is responsible for doing that. Is it the army, which is officially sovereign in occupied territory, or is it Israeli police? There’s a sort of passing-the-buck process that’s been going on there for many, many years. But there’s been an escalation in that problem or a much greater evasion of responsibility on the issue of preventing settler violence under the current government. Because in the current political constellation, this is certainly the most right-wing government Israel has had. Usually coalition governments in Israel span more of the political spectrum; that’s the nature of multi-party systems. Because Prime Minister Netanyahu is such a polarizing figure not just on big political issues but also because he’s under indictment and, in fact, on trial for corruption, he has been able to form a coalition only by relying on the far right, and his own party has become more extreme under his personal influence. And in particular, under this government, the ministry in the Israeli government that is responsible for the police is under the control of the most far-right party in the government, what’s known as the “Jewish Power” party (Otzma Yehudit). The police appear to be doing virtually nothing to stop settler violence, and this has increased drastically because it was an existing problem before that but has increased significantly, especially during the war, and it is just one more sign of the security failures of Netanyahu’s government.

Wyoming Star: So is there any chance for changing the policies, or is it going to be worse?

Gershom Gorenberg: First of all, I’m going to say to you again, I don’t report the future. I would say that the best hope of exchanging policy would be the fall of a government and the establishment of a new government that had different policies. The maximum term of the current government is through next fall (the next Knesset election is set to Autumn 2026.) Of course, in the parliamentary system, a government can fall and elections can be held before it completes its term. In a coalition government system, you’re constantly reading about coalition crises and the potential fall of government, and then one day you wake up and find out it actually happened. And then you have elections in which there are multiple parties, and you really don’t have any idea until the election actually takes place. No, that’s not true; even when the election takes place, you don’t know yet, usually, who is going to make up the next government, as is common in multi-party systems. They have to put together a coalition. Who will be included in the coalition? Who will be ruled out as being part of the coalition? The Americans say, “It’s not over till the fat lady sings.” Until all the votes are counted, you don’t know who’s going to be in power, but in a multi-party system, you don’t know who’s going to be in power even after all the votes are counted; it can take weeks or months to find out. So a different government could obviously take a very different policy toward this problem, and inside of Israel, I’m going to stress this because I think that this is something that is incredibly underreported in foreign news coverage of Israel:

There’s immense opposition to the government. It’s a very unpopular government; polling shows that the parties making up the current coalition would be extremely unlikely to win a majority in a new election. There are constant large-scale protests against the government.

Those protests focus, among other things, on the government’s attempts to change the political system in an undemocratic way and on its failure to reach a hostage agreement and end the war, but additional issues that are constantly part of the anti-government protests are the demand for a commission of inquiry into who is responsible for the disaster of October 7th and the constant call for new elections to replace the government. So that is the roiling Israeli political scene. And how that will play out is, once again, something I would be foolish to predict.

Wyoming Star: In your assessment, are the settlements a net positive or a net negative for Israel overall at the moment as they are functioning right now?

Gershom Gorenberg: Today and in the past, as I have argued at length in my books and in my reporting, the settlements are damaging to Israel in innumerable ways. They are, as I said, a major impediment to reaching a peace agreement with the Palestinians. They’re not the only impediment; there’s obviously also the issue of Palestinian positions and Palestinian willingness to make an agreement. But from the Israeli point of view, the settlements are a tremendous barrier to reaching a peace agreement, which is essential for Israel’s future. The settlements are damaging to Israel’s democracy in multiple ways. The settlements are a huge economic burden on Israel. The settlements are a huge military burden on Israel. The settlement project is, in my view, an ongoing disastrous policy mistake by successive Israeli governments. And I would stress that I say that from the point of view of somebody who is an Israeli and deeply concerned about my country’s future and committed to my country’s future. My critique of the settlements is based on, most basically, the damage that they do to the state of Israel and the danger that they pose to Israel’s future.

The latest news in your social feeds

Subscribe to our social media platforms to stay tuned