Northwest Wyoming Elk Hunting Faces Uncertain Future as Disease Threatens Herds

For decades, elk hunting in northwest Wyoming has been a hallmark of the region’s outdoor culture, drawing thousands of hunters each year to pursue some of the healthiest elk herds in the country, WyoFile reports.

But that golden era may be approaching an inevitable, if unfortunate, end.

On June 19, Wyoming residents will log onto the Wyoming Game and Fish Department’s website, hoping to secure tags for cow and calf elk in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. These hunts, particularly in the Jackson, Fall Creek, Afton, Piney, Pinedale, and Upper Green River herds, have long offered bountiful opportunities on public land.

However, wildlife experts warn that the future of elk hunting in these areas is at serious risk due to the spread of chronic wasting disease (CWD) — a fatal, transmissible neurological illness that is slowly infiltrating northwest Wyoming’s feedground-dependent herds.

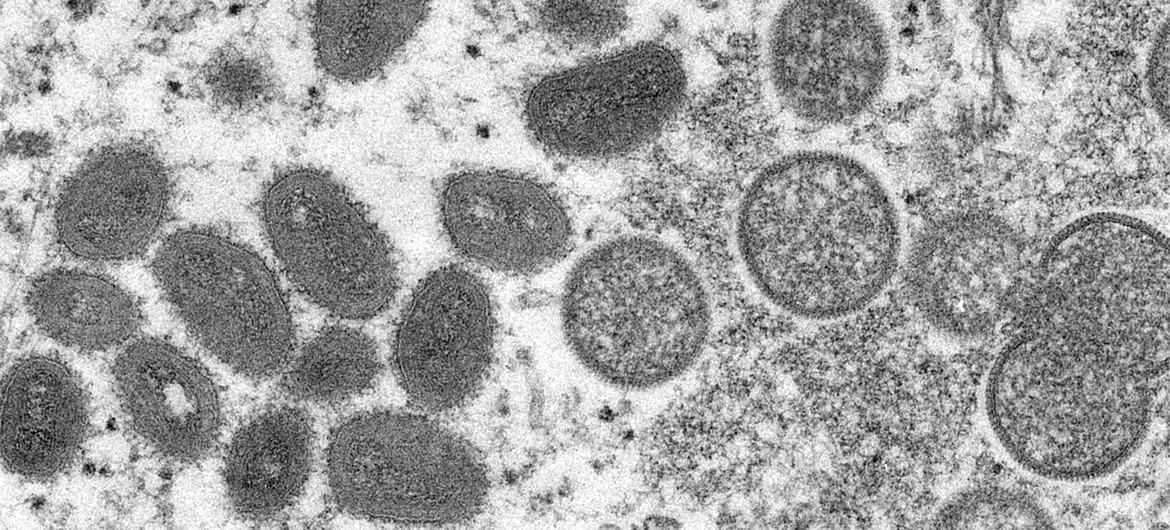

CWD is caused by abnormal prions that can persist in the environment for years. Once contracted, it dramatically shortens an elk’s lifespan. Although some herds in other parts of Wyoming have lived with low levels of CWD for years, the feedgrounds of northwest Wyoming — where thousands of elk congregate in tight quarters over winter — present conditions ripe for rapid disease spread.

Experts predict that, within a decade, hunting cow elk in six major herds could be discontinued. Not because of conservation successes, but because CWD may reduce herd sizes below management thresholds, eliminating the need — or ethical justification — for harvesting female elk.

In anticipation of this shift, some wildlife managers have called for increased hunting now, particularly of cow elk, to proactively reduce herd sizes and dependency on feedgrounds. Others fear that such actions are too little, too late.

At the heart of the issue are Wyoming’s feedgrounds, a century-old system used to support elk populations through winter by providing hay and alfalfa. While these feedgrounds protect elk from starvation and reduce conflicts with ranchers, they also facilitate close contact and high disease transmission rates.

Scientists and wildlife managers are increasingly concerned that if feedgrounds remain operational, CWD prevalence could soar. Projections from the US Geological Survey suggest CWD rates could reach 42% in fed herds over the next 20 years — a dramatic increase from current highs around 10%.

Among the hunting community, the response has been mixed. While some call for aggressive population control and herd restructuring to curb CWD’s spread, many remain skeptical or dismissive of the scientific forecasts. Retired wildlife health expert Hank Edwards expressed concern that public awareness remains low despite the looming threat.

“There’s this attitude of: ‘I’ll hunt for 10 more years and then I’ll be too old to care,'” Edwards said.

Outfitters, who depend on robust elk populations for their businesses, have been especially wary. Some have denied the severity of CWD altogether, suggesting that concerns are overstated or driven by internal agendas. Others acknowledge the problem but resist drastic changes like feedground closures, which could disrupt hunting traditions and local economies.

The Wyoming Game and Fish Department is constrained by legislation passed in 2021 that gives feedground closure authority to the governor and requires consultation with the Wyoming Livestock Board. The department’s long-term feedground management plan relies on building consensus — a slow and politically delicate process.

The coming years may serve as a “real-life test case,” said wildlife biologist Justin Binfet, as northwest Wyoming becomes the frontline for observing how CWD spreads through highly concentrated elk populations.

According to projections, herd sizes may decline by over 50% in some areas. If that happens, the risk to hunters grows too. There’s no confirmed case of CWD infecting humans, but agencies like the CDC and WHO advise against eating meat from infected animals. As prevalence rises, nearly half of all bull elk harvested in certain areas could end up in dumpsters rather than freezers.

Despite the warnings, broad public or political action has yet to materialize. Experts fear that by the time the effects of CWD are widely felt, it may be too late to reverse them.

“From all that we know about prion diseases,” said Edwards, “the populations are not going to recover.”

The latest news in your social feeds

Subscribe to our social media platforms to stay tuned