EXCLUSIVE: Legal Outlook on the Houthi “Blockade” of Israeli Shipping

Since late 2023, Yemen’s Houthi movement—officially known as Ansar Allah—has engaged in an aggressive maritime campaign targeting Israeli-linked shipping in the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden. The Houthis publicly describe their actions as a “maritime blockade” against Israeli interests, particularly in response to Israel’s military operations in Gaza. For almost 2 years the Houthis have been launching missile and drone attacks on commercial ships with ties to Israel, citing support for Palestinians in Gaza as their justification.

Despite the rhetorical use of the word “blockade,” international legal experts have questioned whether the Houthi campaign meets the definition of a blockade under international law. Wyoming Star dove deeper into the legal status of the Houthi actions, the nature of blockades in both international and non-international armed conflicts, and the implications for state and non-state actors under the laws of war.

According to the San Remo Manual on International Law Applicable to Armed Conflicts at Sea and customary international humanitarian law (IHL), a blockade is a method of warfare in which a belligerent seeks to prevent all maritime traffic to and from enemy ports. The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) clarifies that for a blockade to be lawful, it must:

- Be declared and notified to all belligerents and neutral parties;

- Be effective—meaning it must be capable of preventing ingress or egress;

- Be non-discriminatory, applying equally to all neutral ships, regardless of flag;

- Comply with the principles of proportionality and distinction.

According to experts such as Dr. Laurie R. Blank (Clinical Professor of Law and Director of the International Humanitarian Law Clinic at Emory University School of Law), the Houthi actions do not meet the legal definition of a blockade. Instead, they are more accurately characterized as selective attacks on commercial shipping, often linked (or purportedly linked) to Israel or Israeli allies.

As Dr. Blank puts it:

“A blockade is an operation by which a belligerent in an armed conflict completely prevents movement by sea to or from a port or coast belonging to an enemy belligerent in that conflict. In order to be a legal blockade, it has to be complete—meaning against all shipping—but the Houthis are not blocking all shipping. They are attacking specific commercial shipping linked to Israel—and attacking civilians or civilian vessels for a political purpose, which is international terrorism.”

Thus, while the Houthis may politically label their activities as a “blockade,” they fail to satisfy the requirements of effectiveness, impartiality, and scope necessary under international law. Targeting only Israeli-flagged or Israeli-affiliated ships is inherently discriminatory and insufficient to establish a valid blockade.

Under international humanitarian law, the classification of a conflict is critical to determining the legality of methods used. In an interview with Wyoming Star, Dr. Allen S. Weiner, Senior Lecturer in Law and Director of the Stanford Program in International and Comparative Law at Stanford Law School, stated:

“The conflict involving Yemen is what we call a non-international armed conflict in the sense that it’s not a conflict between two countries or between two states. So the Houthis are a non-state armed group. They’re not the recognized government of Yemen—they are an opposition group. The matter is not entirely free from doubt, but I would say that the general view is that it’s only permissible to use blockades in an international armed conflict. I think we would say that the Houthis don’t have the authority under international law to impose a blockade against a state.”

Even if one accepted the rare view that a blockade might be legal in a non-international armed conflict, the Houthi actions still fail to meet essential conditions:

“A blockade is supposed to be effective. In other words, it’s supposed to be able to prevent vessels from traveling to the belligerent state that is being blockaded. A simple paper blockade that is selective, which interferes with some efforts to engage in shipping and in commerce with the blockaded state, is impermissible. I think the Houthis are using the word “blockade” in a political sense. They’re not really talking about a real blockade, which would require them to deploy warships that would prevent vessels from being able to travel in and out of Israeli ports or at least would be subject to boarding and inspection by warships. And the threat of bombing vessels doesn’t meet the requirement of effectiveness. It’s also supposed to be impartial—a blockade is supposed to apply to any shipping from any neutral vessel. As I’ve seen, the Houthis have been talking about targeting only Israeli flag vessels. So there are a lot of issues.”

As Dr. Weiner puts it:

“The concept of an act of terror doesn’t actually really have much legal force, at least as an international law matter. We don’t really have a definition of what terrorism is under international law. There are about 19 different multilateral treaties that apply to discreet kinds of actions that are considered to be counterterrorism treaties. Killing of internationally protected persons, aircraft sabotage, etc. The answer is most states, when they’re engaged in armed conflict with a non-state armed group, call the non-state armed group a terrorist organization. But international law recognizes the status of what we call non-international armed conflicts—conflicts between a state and a non-state armed group. An act of terror is a political concept. I don’t think it actually does much work in terms of understanding the legal status. So I think that the blockade is an illegal use of force by the Houthis against Israel.”

Whether these acts are best characterized as unlawful uses of force, armed attacks, or acts of terror depends in part on the forum and the actor making the judgment.

The situation looked rather different in the past. According to Dr. Weiner:

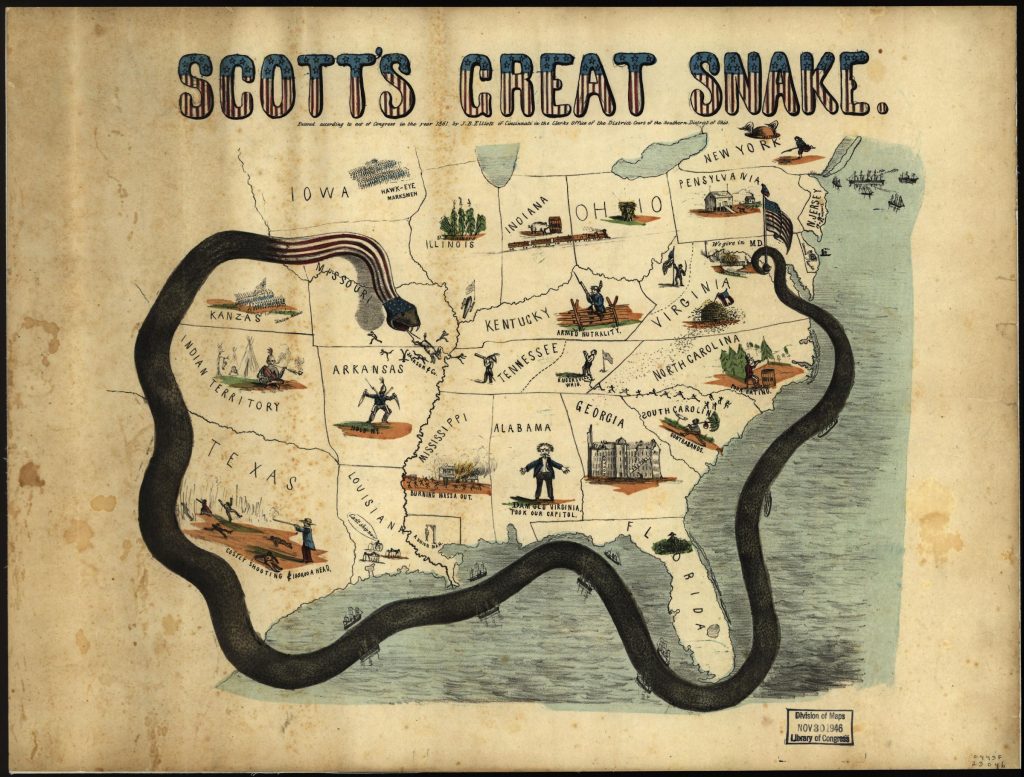

“In the old days before the UN Charter, there used to be a notion that if a rebel group gained enough control over territory, even if it had not been recognized as an independent country, it would acquire the status of being a belligerent. There used to be recognized circumstances of belligerency. And in those cases it was permissible to impose a blockade against the non-state group that was belligerent. I mean, one of the most famous examples is the US Civil War. The union, the north, imposed a blockade on the Confederacy. We didn’t recognize the Confederacy as an independent country, and today it would not be seen as a war between two countries. It would not be seen as an international armed conflict. But under the law that applied at the time the Confederacy had gained enough control, it had an organized fighting military force, and so it qualified as a belligerency. One of the first things that President Lincoln did was impose a blockade on the Confederacy, and there are some early cases from the Supreme Court, the so-called Prize Cases, in which the Supreme Court was asked whether it was lawful for the president to impose a blockade on the Confederacy. Another more contemporary example that we might be familiar with is the blockade of Cuba during the Cuban missile crisis. This was a blockade imposed largely by the United States. We argued that it had been authorized by the Organization of American States and this was to basically prevent vessels from reaching Cuba. It was not an effort to choke off all trade with Cuba, but we were trying to make sure that no weapons were being allowed to enter Cuba. So we established a search practice.”

If an impartial blockade is questionable legally, what does a lawful response to a rogue state look like? Dr. Weiner gave the following answer:

“Let’s assume that what Israel is doing or some aspects of what Israel is doing in Gaza are illegal. I think it is generally accepted that states are allowed to engage in responsive measures. They’re allowed to take what are known as countermeasures in order to respond to illegality. For instance, states can certainly say, “Well, I’m no longer going to provide you with assistance; I’m no longer going to ship you weapons; I’m no longer going to provide you with economic aid because I object to what you’re doing; I think what you’re doing is illegal, and I want to try to dissuade you from doing that.” It might also be that if what Israel is doing is illegal, other states might be able to violate legal obligations that they otherwise owe to Israel as a countermeasure. Let’s say there’s a bilateral aviation agreement between Israel and, say, France. And France says, “I think what you’re doing is illegal, and so I’m now going to suspend flights under our aviation agreement.” Again, it’s a kind of sanction that states are taking. Countermeasures of this kind are generally permissible if a state is violating its international legal obligations. However, it’s not permissible to use force by way of countermeasures, and I think what the Houthis are doing to the extent they’re lobbing missiles at Israel clearly is a use of armed force. The stated blockade involves the threat to target warships, and it’s not permissible for me. If I think another country is violating its obligations, I can only use force against that country if I have been the victim of an armed attack and I’m exercising self-defense or if I am engaged in self-defense of another state that has been the victim of an armed attack.”

Under Article 51 of the UN Charter, a state has the right to use force in self-defense if it suffers an armed attack. The Houthi attacks, which have involved missiles and drones launched at commercial and potentially military vessels, likely constitute armed attacks, thereby triggering Israel’s right to defend itself.

Dr. James Kraska, Charles H. Stockton Professor of International Maritime Law and Chair of the Stockton Center for International Law at the US Naval War College and Visiting Professor of Law and John Harvey Gregory Lecturer on World Organization at Harvard Law School, wrote in a statement to Wyoming Star:

“Blockade is an act of war and regarded in customary law as unlawful aggression. Consequently, Israel has a right of self-defense against these threats, and it may collaborate with other states, such as the United States and the United Kingdom, in collective self-defense. Strikes against Houthi forces may be conducted to eliminate the ongoing threat, using such force as is necessary to stop the threat. The attacks by Western nations may continue so long as the threat persists. Because the government of Yemen is unable to stop the attacks by Houthi forces. Western states may strike the Houthi missile complex and supply chains in Yemen or in international waters.”

Dr. Weiner further clarifies the extent to which Israel, the US, and their allies can respond to armed attacks:

“There is basically a question of whether you have a right to use force and then a question about the means by which you carry out the use of force. And the key principles governing the use of force are the principles of distinction, which is to say you may only attack military objects, not civilian objects, and then there’s also a principle of proportionality, which provides that if you do direct your military operations against a military objective but you foresee that there might be unintended civilian harm, you can’t launch the attack if the civilian harm will outweigh the military advantage. So those are the fundamental principles of the conduct of the use of force. Also, the principle of precaution, which says that you have to take all feasible measures to try to minimize civilian casualties.”

Western forces have already conducted military operations to neutralize Houthi threats in the Red Sea. These are framed as operations to preserve the freedom of navigation, a cornerstone of international maritime law. The latest US campaign ended up unsuccessful, with the US striking a deal with the Houthis.

The UN Security Council has previously passed resolutions concerning Yemen, including the designation of the Houthis as a destabilizing force (e.g., UNSC Resolution 2624). However, enforcement against non-state actors like the Houthis remains difficult. As Dr. Weiner notes,

“Unlike in our domestic legal system, in international law there’s not necessarily a compulsory means of bringing states before an international court, and there’s no world government that is in a position to enforce international law. Most of international law is enforced horizontally; that is to say, it’s enforced through self-help. We don’t necessarily have an assured mechanism of bringing parties before an international court and having an international police force that will enforce the law, especially when we’re dealing with a non-state group like the Houthis. Some years ago there was a blockade imposed by the Saudis and other Gulf states against the Houthis. The Saudis and the Emirates waged war for several years against the Houthis, so this would be how international law tends to be enforced.”

The Houthi maritime campaign is not a legal blockade. It lacks the necessary legal structure, impartiality, and enforcement mechanisms and is carried out by a non-state actor in the context of a non-international armed conflict. Rather than a lawful act of war, it is better understood as a series of armed attacks and acts of asymmetric warfare.

Calling the Houthi operations in the Red Sea a blockade or a terrorist act is largely a political statement and holds little weight in the legal discussion on the matter.

As Dr. Weiner puts it:

“There are lots of things out there that might be good or bad ideas. That’s not to say that they’re legal or illegal. I often refer to the concept of policies that are lawful but awful. Not everything that’s a bad idea is illegal, and not everything that’s a good idea is legal. We have to understand what the role of law is. Understanding the difference between policy questions and legal questions is something that we always have to be mindful of.”

Learn more about the economic side of the Houthi blockade here.

The latest news in your social feeds

Subscribe to our social media platforms to stay tuned