Vietnam has officially ended its decades-old two-child policy in an effort to counter a declining birthrate and reduce the long-term economic and social pressures of an ageing population.

According to Vietnamese media reports, the government lifted all restrictions on family size this week, giving couples the freedom to have as many children as they choose.

Health Minister Dao Hong Lan said the move was necessary to support Vietnam’s future, warning that a shrinking population could undermine sustainable development, national security, and economic progress.

“Population decline poses a threat to our long-term stability,” she said, as reported by the Hanoi Times.

Between 1999 and 2022, Vietnam maintained a relatively stable birthrate of around 2.1 children per woman—the replacement level needed to sustain a population. However, the rate has since dipped. In 2024, it hit a record low of 1.91, raising alarms among policymakers.

Like many of its regional neighbors—including Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and Singapore—Vietnam is confronting the social and economic effects of falling fertility. Unlike those more developed economies, however, Vietnam’s demographic challenge comes before it has fully industrialized or achieved high-income status, prompting fears of “growing old before getting rich.”

According to the World Bank, the country’s working-age population is expected to peak by 2040, making population policy a key issue for the government’s long-term planning.

Vietnam first introduced the two-child limit in 1988, during its transition from a centrally planned economy to a market-oriented one. At the time, the policy aimed to ensure enough resources for development and post-war recovery. While the rule was especially strict for Communist Party members, families with more than two children often faced cuts to government benefits and social services.

Now, the policy reversal marks a dramatic shift. Authorities are not only encouraging births but also addressing deepening demographic imbalances, including a skewed sex ratio and regional disparities in population growth.

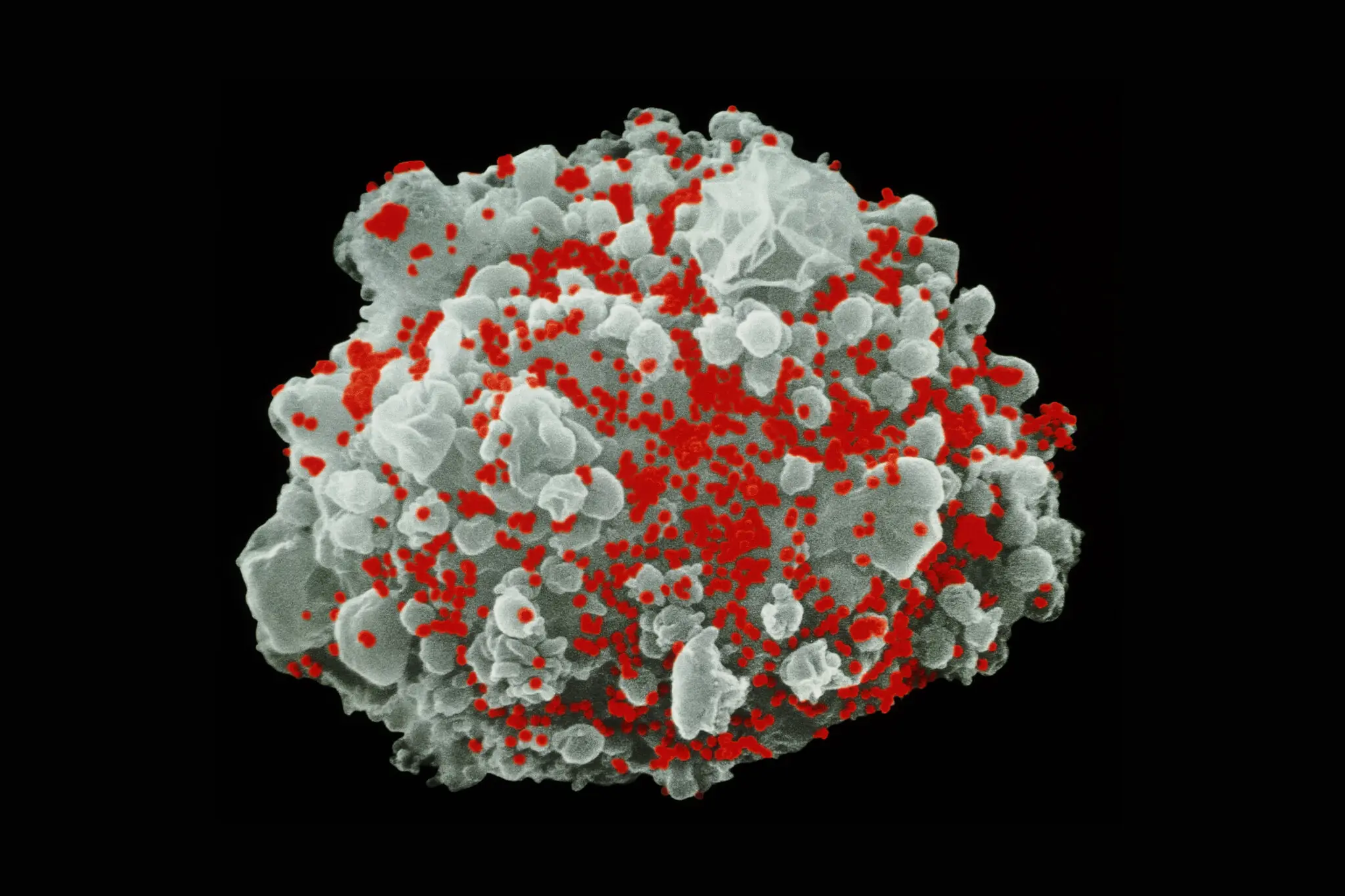

The Ministry of Health highlighted significant regional and gender-based disparities. In 2024, Vietnam’s sex ratio at birth stood at 111 boys for every 100 girls—well above the natural average. The imbalance is most acute in the northern regions, such as the Red River Delta and Northern Midlands, and least severe in the Central Highlands and Mekong Delta.

Although Vietnam prohibits doctors from disclosing the sex of a fetus to prevent sex-selective abortions, reports suggest some medical practitioners continue to circumvent the rules using coded language.

The General Statistics Office has warned that, without intervention, Vietnam could face a surplus of 1.5 million men aged 15–49 by 2039, rising to 2.5 million by 2059.

To combat this, the Ministry of Health has proposed tripling penalties for illegal fetal sex selection, with fines potentially reaching $3,800.

Vietnam’s lowest birthrates are concentrated in major cities like Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City, where high living costs, housing challenges, and work-life pressures make large families less feasible. Officials say reversing the trend will require not just policy changes, but broader support for parenting, childcare, and economic stability.