How the 1925 Gros Ventre Landslide Shaped Modern Approaches to Flood Prevention in Yellowstone Region

As the centennial of the 1925 Gros Ventre Slide approaches, geologists and hazard researchers are reflecting on how the event not only transformed a Wyoming valley, but also provided critical lessons that helped avert disaster decades later during the 1959 Hebgen Lake earthquake, Billings Gazette reports.

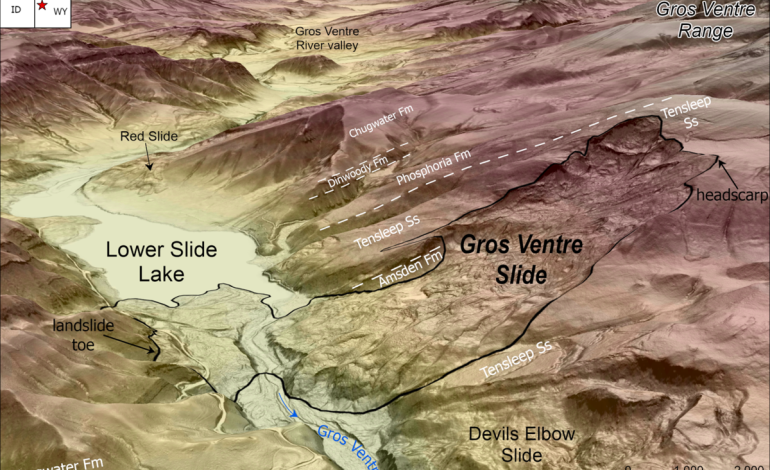

On June 23, 1925, around 4 p.m., roughly 50 million cubic yards of rock and debris cascaded down Sheep Mountain, northeast of Jackson, Wyoming, burying the Gros Ventre River valley and damming the river to form Lower Slide Lake. While no lives were lost during the slide itself, the event set the stage for a devastating flood two years later. In May 1927, the dam created by the landslide was breached by snowmelt-swollen waters, causing a catastrophic flood that destroyed the town of Kelly and killed six people.

According to James Mauch, a geologist with the Wyoming State Geological Survey, the event remains one of the most significant landslides in the Greater Yellowstone region. The geological conditions that contributed to the slide—a combination of steep slopes, permeable sandstone, saturated soils, and possibly seismic activity—are still present in the region today.

The landslide was triggered by a unique combination of hydrological and geological factors. Beneath the surface, water-permeable Tensleep Sandstone overlays less-permeable Amsden Formation shale, creating a zone where groundwater accumulates. Saturated weak layers within this interface likely gave way after weeks of unseasonably wet weather, possibly compounded by a moderate earthquake just 20 hours before the collapse.

Researchers believe that a similar chain of events—liquefaction of saturated layers followed by mass slope failure—caused the dramatic transformation of the landscape. Today, the scar of the landslide and the remains of the debris field remain highly visible.

The insights gained from the Gros Ventre event proved crucial decades later. After the 1959 Madison Slide, which was triggered by a magnitude 7.3 earthquake near Hebgen Lake, engineers acted quickly to prevent another flood disaster. Drawing from the experience at Kelly, they constructed a spillway to manage water buildup behind the newly formed landslide dam, successfully avoiding a repeat catastrophe.

This proactive response, informed by past experience, underscores how historical geologic events continue to inform present-day hazard mitigation strategies in the Yellowstone area and beyond.

While geologic conditions in the Yellowstone region remain conducive to landslides, scientists now benefit from advanced tools such as lidar mapping and landslide susceptibility models. These technologies help researchers and local officials better understand where future slides may occur and how best to prepare.

The Yellowstone Volcano Observatory, along with state and federal partners, continues to study geologic hazards like landslides, earthquakes, and volcanic activity. Their work builds on the lessons of events like the Gros Ventre Slide, helping communities stay informed and resilient.

Although 100 years have passed since the Gros Ventre Slide, the risk it highlighted remains real. The Greater Yellowstone region is a geologically active landscape, and its history of landslides serves as both a warning and a guide.

As Mauch notes, “The legacy of the Gros Ventre Slide is not just the altered terrain, but the knowledge gained—knowledge that has saved lives and continues to shape how we manage natural hazards today.”

The latest news in your social feeds

Subscribe to our social media platforms to stay tuned