As President Donald Trump’s administration approaches a key self-imposed deadline to finalize a wave of trade deals, tariffs have once again taken center stage in US economic policy, CNN reports.

With the possibility of higher duties on dozens of countries beginning as soon as August, questions are resurfacing about the broader goals behind Trump’s tariff agenda.

Since returning to office, Trump has employed tariffs not only as a trade enforcement tool but as a cornerstone of his administration’s efforts to reshape the global economic order. The motivations behind these actions, while varied, generally align with four main objectives:

Revitalize US manufacturing

Raise government revenue

Correct trade imbalances

Exert leverage in international negotiations

While tariffs have delivered some immediate outcomes—ranging from trade concessions to company investment announcements—the long-term effectiveness of the strategy remains subject to debate.

A key argument behind the use of tariffs is that they incentivize companies to manufacture products domestically by making imports more expensive. Trump has framed this approach as a way to reopen factories, restore blue-collar jobs, and revive the American industrial base.

In support of that vision, some companies—including Apple, GE Appliances, and General Motors—have announced large US investments. However, many of these projects were planned independently of tariff policy and often take years to implement. Complicating the goal is a labor shortage in the manufacturing sector: as of May, there were over 400,000 unfilled manufacturing jobs in the US.

At the same time, manufacturing employment has declined in recent months. Despite early job gains, the net number of manufacturing jobs under Trump’s current term has slipped, calling into question the sustainability of the strategy as a job creation engine.

Trump has repeatedly claimed that tariffs could generate enough revenue to lower—or even eliminate—federal income taxes. In reality, economists estimate this would require extremely high tariff rates on all imports, likely between 100% and 200%, which could significantly disrupt both prices and demand.

Currently, the US imports about $3 trillion in goods annually, and the Treasury has reported under $100 billion in total tariff revenue since Trump took office. Some of the most aggressive tariffs are also intended to be temporary—such as those on Canada, Mexico, and China related to drug enforcement efforts—further limiting their long-term revenue potential.

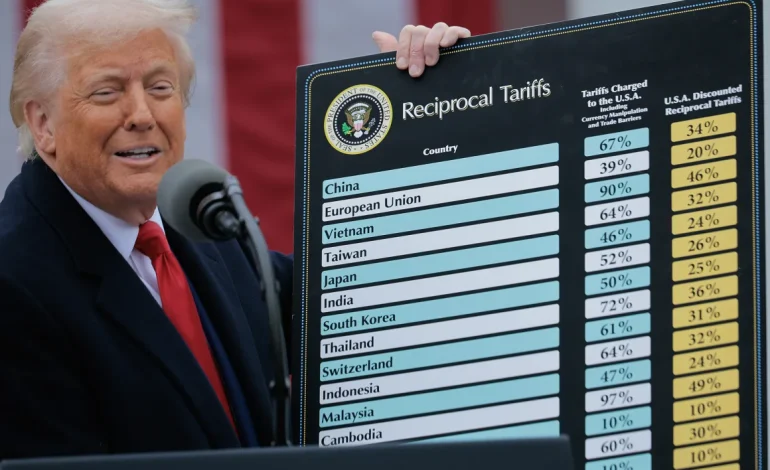

Trump has frequently described trade deficits as evidence of unfairness, arguing that reciprocal tariffs are necessary to balance economic relationships. In April, his administration introduced new “reciprocal tariffs” based on the size of US trade deficits with individual countries.

Early data showed a sharp drop in the goods trade deficit—from about $130 billion in April to roughly $60 billion in May—largely due to a decline in imports following steep tariffs. However, the gap widened again the following month, reflecting volatility rather than a lasting trend.

Economists caution that trade deficits are not necessarily signs of economic weakness and can even signal strong domestic consumption. Moreover, many imported goods are not easily replaced by American-made alternatives.

Perhaps the most immediate impact of Trump’s tariff policy has been its use as leverage in global negotiations. Threats of higher tariffs have, in some cases, prompted countries to alter policy—such as Canada recently shelving a proposed digital services tax after pressure from Washington.

Still, not all targets have responded as expected. Tariffs have not curbed the flow of fentanyl into the US, nor have they led to major shifts in Apple’s manufacturing footprint or major repatriation of US auto production.

And when countries do comply, the tariffs often need to be lifted, which undermines the administration’s revenue goals.

Trump’s tariff strategy has yielded several early wins, but critics argue that its goals often work at cross-purposes. A single policy tool cannot simultaneously maximize revenue, reduce trade deficits, incentivize domestic production, and compel foreign governments to act—all without economic trade-offs.

For example:

If companies manufacture in the US, they are exempt from tariffs—meaning no revenue is collected.

If tariffs are removed after negotiations succeed, they no longer help reduce trade imbalances.

If prices rise too sharply, it can strain US consumers and reduce demand for American goods.

Nonetheless, Trump continues to view tariffs as a flexible and powerful mechanism for shaping global trade in America’s favor.

“If you don’t make your product in America… you will pay a tariff,” Trump said in March.

The latest news in your social feeds

Subscribe to our social media platforms to stay tuned