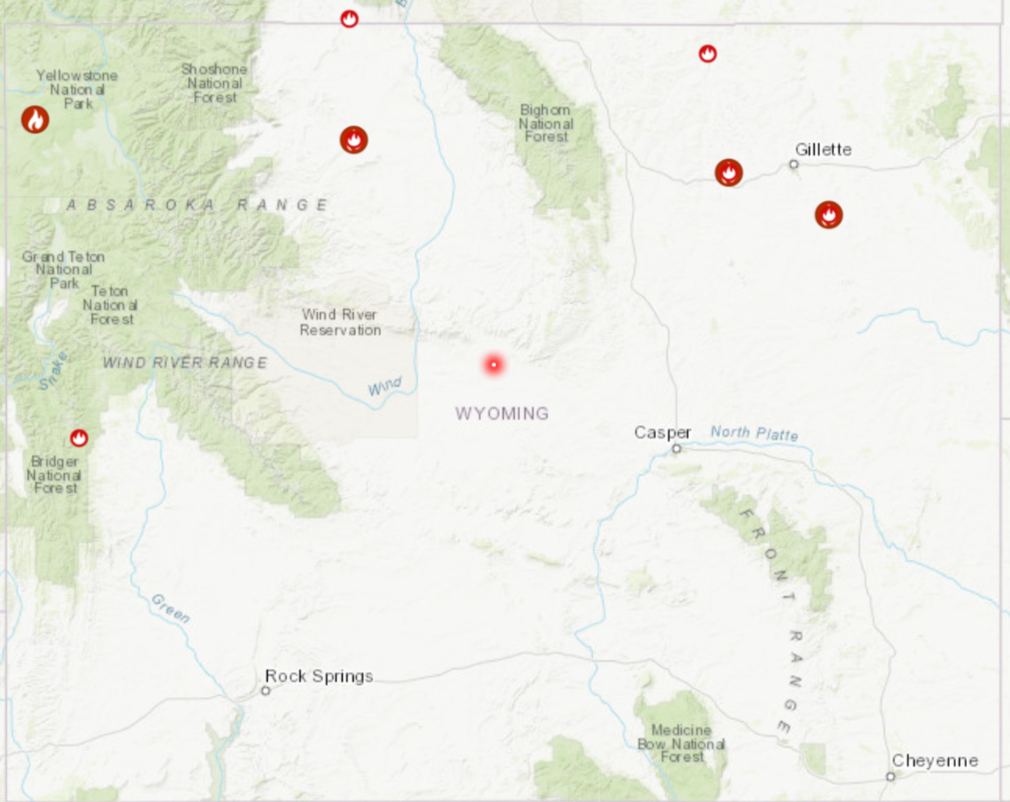

As the 2025 wildfire season continues, communities, scientists, and land managers across Wyoming and out of state are watching conditions closely. The season, typically active from June to September, has already seen significant fire activity fueled by unusually dry and warm weather patterns.

According to forecasts from the National Interagency Fire Center and Climate Prediction Center, above-normal fire potential was predicted for southwestern Wyoming in June and July, shifting to northeastern parts of the state by late summer. Long-term weather trends, including persistent above-average temperatures and reduced precipitation, have left fuels—grasses, shrubs, and timber—especially dry and easily combustible.

The 2025 season’s first major blaze, the Horse Fire, was ignited by lightning on June 13 in Sublette County’s Bridger-Teton National Forest. The fire spread rapidly due to heavy fuels and erratic winds, reaching over 2,300 acres by late June. More than 230 personnel were deployed to combat the flames, which prompted several road and trail closures.

A series of dry lightning storms in early July triggered additional fires across central and northern Wyoming, challenging containment efforts. Real-time tracking by platforms like Frontline Wildfire Defense and the Fire Weather & Avalanche Center has been crucial in keeping communities informed.

The environmental cost of intense wildfires remains a growing concern. The 2024 season burned approximately 840,000 acres—the most since the 1988 Yellowstone fires—setting a high-stakes backdrop for 2025.

“Fire is a critical process that many plant and animal species rely on… Hence, fire serves a key role in maintaining diverse and healthy ecosystems in the western US,” said Dr. Dave McWethy, Associate Professor of Earth Sciences at Montana State University. “More intense and large fires can have a longer legacy impact on ecosystems that the plant and animal species may not be as well adapted to. This is perhaps one of the concerns of a trend in larger, hotter fires burning more frequently in some western US states. We find that in drier settings, post-fire tree establishment is low because soils are drier and temperatures are warmer. The result is these typically lower elevation, dry settings are not returning to forest after fire—mostly grasses and shrubs.”

Dr. McWethy adds that this change isn’t inherently negative but does represent a transformation in landscape identity and function.

Species like elk and mule deer, already impacted by previous burns such as the Elk Fire in the Bighorn National Forest, face altered migration paths and forage availability. Recovery of these areas is ongoing, with trail and access restrictions in place to minimize further disturbance.

Fire prevention agencies continue to encourage personal responsibility and community readiness. Guidance includes limiting campfire use, preparing defensible spaces around properties, and planning evacuation routes—especially during the peak danger window of July to September.

At a state level, Wyoming Game & Fish and forestry departments are focusing on habitat restoration, trail repair, and fuel reduction projects. Restoration grants and community wildfire mitigation funds have been made available to support these efforts.

University of Utah School of Biological Sciences Professor Dr. William Anderegg highlights the importance of scaling up local interventions:

“Because climate change is driving around half of the wildfire area burned, reducing the speed of climate change is crucial. For local to regional action, proactive forest management, including fuel treatments and prescribed fires, can reduce risk in many ecosystems and places. We need more capacity, funding, planning, and science to be able to scale up the amount of area treated by these techniques to reduce risk to communities and ecosystems. Finally, at individual levels, being especially careful during dry conditions to avoid activities that could ignite fires (e.g., unattended campfires, car chains and sparks, cigarettes, etc.) is crucial.”

The interplay of natural and human-caused ignitions complicates fire management in a warming world. While lightning remains the dominant natural cause, human-related ignitions—like campfires, equipment sparks, or powerline faults—are increasingly influential.

(Clearmont Fire Department)

“In general, natural causes are dominated by lightning strikes, while human causes include a wide range of activities, usually associated with carelessness or aging infrastructure (power lines),” noted Dr. Paul Brooks, a University of Utah professor in geosciences. “The human activities are ones we can control. The other part of the issue is environmental susceptibility to fire of our forests resulting from climate and historical management.”

Dr. Brooks emphasized that cost and complexity limit the widespread use of preventative forest management:

“All methods are seldom used, primarily because of the costs associated with management. The timber itself, especially in the densest, most at-risk forests, is usually not valuable enough to pay for logging. In the few places it is, we don’t have the mills to process the timber, and transportation costs make it harder to justify. Not to mention that these forests serve other functions for society beyond the timber, including water supply, recreation, habitat, etc.”

In case a solution to the financing hurdle is found, Dr. Brooks proposes the next logical step: creating site-specific forest management plans that incorporate feedback between forest structure and local hydroclimate (sun, shading, wind, snow accumulation and melt, etc.).

“Rather than individual trees, there is growing evidence that a mixture of forest stands and meadows can keep the system wetter and possibly more fire resistant.”

He pointed to collaborative models like Blue Forest, which engage utilities, governments, insurers, and health sectors to collectively fund forest management as a shared-risk investment.

Wyoming residents are turning to online tools like the Frontline Wildfire app and the Fire Weather Avalanche Center’s interactive map to stay updated on active fires, smoke plumes, and weather alerts. Meanwhile, the WYWRAP program assists communities in identifying high-risk areas and planning site-specific mitigation strategies.

With forecasts indicating continued elevated fire risk into late summer, land managers and scientists stress the importance of vigilance, ecological awareness, and resource allocation.

As Dr. Brooks concluded, “If we want to protect forests, water supply, and human structures from forest fire, we need to increase the pace of active management to mitigate the growing threat.”

The latest news in your social feeds

Subscribe to our social media platforms to stay tuned