EXCLUSIVE: Iran, Armenia, Azerbaijan—and a Corridor That Could Rewire the Caucasus

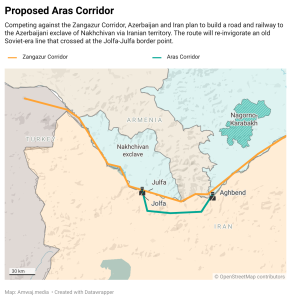

Once again, peace talks, power struggles, and strategic anxiety intersect in the South Caucasus. Armenia and Azerbaijan, after decades of bloody conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh, signed a US-brokered agreement on August 8, 2025. The deal replaces the long-debated “Zangezur Corridor” idea with a US-branded initiative, the Trump Route for International Peace and Prosperity (TRIPP).

For Baku, the project promises long-sought direct connectivity between Azerbaijan and its Nakhchivan exclave. For Yerevan, it offers a path to peace and investment—if sovereignty is preserved. For Tehran, however, it raises alarms about isolation, NATO expansion, and losing its lifeline to Armenia.

Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian rushed to Yerevan on August 18–19 seeking guarantees that Armenia would maintain sovereignty over any new routes. Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan publicly assured him that “any road will be under the exclusive jurisdiction of Armenia,” with Armenian security—not foreign forces—responsible.

Iran has been blunt about why this matters.

“Iran has voiced strong opposition to the proposed Zangezur Corridor, a route linking Azerbaijan to its Nakhchivan exclave through Armenia’s Syunik province. Tehran views the project as more than a trade initiative, casting it instead as a geopolitical maneuver backed by the United States and Israel to diminish Iran’s influence in the South Caucasus,” says Alex Vatanka, Senior Fellow at the Middle East Institute, Senior Fellow in Middle East Studies at the US Air Force Special Operations School (USAFSOS) at Hurlburt Field, Adjunct Professor at DISAS at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, and the author of “Battle of the Ayatollahs,” a book on Iranian foreign policy since 1979. “Officials, including Ali Akbar Velayati, warn that the corridor would cut Iran off from Armenia, undermine its access to vital transit routes, and increase its isolation in regional trade and diplomacy. The plan, they argue, could reconfigure borders and alliances in ways that sideline Iran and bolster Western influence near its borders. Iran also fears the corridor would open the door for NATO to entrench itself between Iran and Russia, a scenario it has called unacceptable. Tehran is especially wary of Turkey’s role, given its NATO membership and growing presence in the Caucasus, and points to Israel’s expanding military and strategic ties with Azerbaijan as evidence of a broader effort to encircle and weaken Iran. While Iran hopes Moscow will share its concerns, it remains uncertain about Russia’s willingness to confront the project outright, leaving Tehran anxious about being squeezed out of a rapidly shifting regional order.”

This fear resonates across Tehran’s policy circles: NATO encroachment, Turkey’s growing regional role, and Israel’s tight security ties with Azerbaijan all paint a picture of Iran being strategically surrounded.

Dr. Mostafa Ghaderi Hajat, Associate Professor at the Faculty of Humanities, Tarbiat Modares University, underscores the stakes:

“The Zangezur Corridor… holds significant geopolitical and geostrategic implications that long predate the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. While Iran welcomed the return of Karabakh to Azerbaijani control, it has consistently opposed the establishment of this corridor, primarily due to concerns over regional balance and sovereignty. Iranian leadership, including the Supreme Leader, has explicitly stated that Iran will not tolerate any attempt to sever its historic border with Armenia. This stance is rooted in the belief that such a corridor would shift the regional power dynamics by increasing Turkish and Azerbaijani influence while simultaneously reducing Iran’s strategic access to the Caucasus. From a broader perspective, the creation of the Zangezur Corridor could isolate Iran by cutting its direct land route to Armenia, making it more reliant on Azerbaijan for regional connectivity. This would not only weaken Iran’s economic and energy transit capabilities but also risk empowering military and intelligence alliances — particularly between Azerbaijan, Turkey, and Israel — in ways that could heighten ethnonational tensions and security threats within Iran.”

In short, Iran sees the corridor not as a road, but as a shift in the balance of power. Further, Dr. Hajat’s analysis on the issue of the Zangezur Corridor can be found in his latest papers for the University of Tehran and the Iranian Association of Geopolitics (in Persian).

Dr. Ahmad Kazemi, Professor of International Law in Tehran and Senior Researcher on Eurasian Issues and senior author and researcher in the field of the Caucasus and Eurasia, frames the issue in legal and sovereignty terms:

“Iran welcomes the peace agreement between Armenia and Azerbaijan, because signing the peace treaty means recognizing the international borders of the two countries. This can curb the ethnic and territorial expansionist intentions of the Republic of Azerbaijan to dominate southern Armenia, which is carried out by applying the fake term “Western Azerbaijan” to Armenia. Iran is not against the opening of communication lines and normal roads between the Republic of Azerbaijan and Armenia. Tehran is against any extraterritorial corridor that violates the sovereignty and territorial integrity of the host country, Armenia, and causes geopolitical changes… There is no legal basis for the request of the Republic of Azerbaijan for a corridor based on the 2020 ceasefire agreement in Moscow. Also, according to international law, the existence of an “extremist zone” (exclave) in Nakhchivan does not give Baku the right to request a corridor.”

Dr. Kazemi argues alternatives already exist, pointing to the Iran-backed Aras Corridor, which Baku can use for road, rail, and energy connections to Nakhchivan. He also stresses that Azerbaijan’s insistence on the term Zangezur signals territorial claims over Armenia’s Syunik province, which he calls a violation of Article 2 of the UN Charter.

At times, Iran’s rhetoric has been combative.

Dr. Arman Grigoryan, an associate professor international relations at Lehigh University, most recently the author of articles about the Second Karabakh War (“Revolutionary Governments, Recklessness, and War: The Case of the Second Karabakh War,” Security Studies, Vol. 33, No. 3 (Autumn 2024), pp. 372-406), and Armenia’s efforts change its strategic orientation (“Armenia’s Misguided Pivot to the West,” National Interest, July 17, 2024) explains:

“Iran has always considered a corridor through Southern Armenia a threat to its vital interests. Such a corridor, if it were to compromise Armenian sovereignty over the region, could potentially deprive Iran of its border with Armenia, which in turn would mean total Azerbaijani control of its access to the north. It would also create an overland link between Turkey and Azerbaijan, which would affect the strategic picture in the region in ways not favorable to Iran. For these reasons, Iran has always been unequivocal and vehement in its opposition to any such projects. On numerous occasions they have even stated that they would be prepared to use force to thwart such ideas. The initial reactions from Iran after the agreement in Washington was reached on August 8, were in line with that posture. In particular, Velayeti made a statement threatening to turn the corridor envisioned in that agreement into a graveyard. Later, however, the president and the foreign minister of Iran, made more conciliatory statements, and reassured their audiences that they have been in contact with their Armenian counterparts and their concerns have been taken into account.”

Dr. Grigoryan notes that the discrepancy reflects internal debates between Iranian moderates and hardliners, as well as uncertainty over Russia’s willingness to back Tehran’s stance.

During Pezeshkian’s visit, Armenia and Iran announced plans to lift ties to the level of a strategic partnership, signing multiple agreements on politics, economy, and culture.

Tehran Times reported Pashinyan’s vow that Armenia would “make no major decision without consulting Iran.” This reassures Iranian audiences while Armenia simultaneously seeks Western investment and closer security ties.

JAMnews noted that Yerevan pitched benefits for Iran, including potential access to the Black Sea through future transit links, while emphasizing “no third-party control” on its soil.

For Baku, the TRIPP deal achieves what it has wanted since the 2020 war: a direct legal link to Nakhchivan and thus to Turkey. Washington’s framing avoids the term “corridor” while still fulfilling Azerbaijan’s core aim.

Dr. Mehran Kamrava, a Professor of Government at Georgetown University Qatar, the Iranian Studies Unit Director at the Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies, situates the corridor in strategic context:

“…For Iran and Armenia, it’s their only land connection, which is important for trade and commerce, whereas for Azerbaijan it is the only link with Nakhchivan. Iran has long been concerned about losing its land access to Armenia and has therefore sought to ensure that the Zangezur Corridor remains accessible. From the Iranian perspective, complete Azerbaijani control over the Corridor would not only make it more difficult to maintain ties with Armenia but further encircle it by countries that are or potentially can be hostile to it. Iran and Azerbaijan have long maintained cordial but uneasy relations with one another. Over the last several decades Azerbaijan has drawn itself to both Turkey, another potential rival to Iran, and to Israel… Iran’s relations with Armenia have long been instrumental. They have not necessarily been commercial and certainly not ideological. Given Tehran’s uneasy relations with Baku and Azerbaijan’s conflict with Armenia, Iran and Armenia have maintained friendly relations. Transactional relationships of this sort are often subject to extraneous developments and are therefore by nature impermanent. One is to watch whether Iran’s close relations with Armenia continue as they have been now that Armenia and Azerbaijan appear to be moving closer to one another.”

Dr. Kamrava notes that despite Aliyev’s reassurances, debate continues in Iran about whether the US-brokered deal leaves Iran—and Russia—as the real losers.

Dr. Kazemi outlines the Iranian position:

“From Tehran’s perspective, Baku and Ankara’s insistence on creating an extraterritorial corridor is in line with NATO’s grand plan, which aims to create a NATO highway from the Mediterranean Sea and Turkey to the Caucasus, the Caspian Sea, and Central Asia. The main goal of creating this corridor is to exclude Iran, Russia, and China from the energy and transit equations of the region and to remove rare and valuable metals from both sides of the Caspian. It seems that one of the goals of creating this corridor is to implement England’s historical plan to create a Turanian world. The Turanian world is supposed to activate ethnic faults in Iran, Russia, and China and transform the original Azerbaijani identity, which is a Shiite and Iranian identity, into a Turkish identity. Changing the title of the fake Zangezur corridor to “Trump’s Route to International Peace and Prosperity” does not change the nature and goals of this plan. Iran, having common borders, is a neighbor of Armenia and the Republic of Azerbaijan and is interested in expanding relations with both countries. Both countries have been part of historical Iran. Iran believes that a regional security system in the Caucasus should be formed based on the 3+3 formula, meaning the participation of the three Caucasus countries and their neighbors (Iran, Russia, and Turkey), a model that I proposed in my 2005 book titled ‘Security in the South Caucasus.’“

But risks remain. Reuters has reported spikes in border clashes around Syunik, underscoring that even as deals are signed, local dynamics could derail progress.

The region now has three possible paths going forward:

- Managed connectivity under Armenian control: Routes operate under Armenian sovereignty with regional oversight, easing trade while keeping Iran engaged.

- Jurisdiction creep: If foreign management expands, Iran could double down on alternatives like the Aras Corridor and harden its stance.

- Spoiler dynamics: Renewed clashes or domestic politics in any capital derail progress, deepening mistrust.

For Azerbaijan, the corridor is a strategic victory. For Armenia, it’s a sovereignty test. For Iran, it’s a red line with existential undertones. As Vatanka put it, this is “more than a trade initiative” — it’s about who sets the rules of the new Caucasus order.

The outcome will depend less on maps than on enforcement: who builds, who guards, and who profits. Armenia is trying to balance sovereignty with growth, Azerbaijan is pressing its advantage, and Iran is maneuvering to avoid being boxed out. The corridor may promise peace on paper, but in practice it’s a litmus test of whether the South Caucasus can remain governed by its own states — or reshaped by the geopolitics of outsiders.

The latest news in your social feeds

Subscribe to our social media platforms to stay tuned