EXCLUSIVE: Armenia’s constitution rewrite. Fast-track to Peace with Azerbaijan—or a Political Booby Trap?

Armenia and Azerbaijan are, on paper, closer to a peace deal than at any point since the early 1990s. The two sides initialed a treaty text in Washington on August 8, and both Washington and Brussels have been cheering them on. But one last, loaded question sits between the draft and the signatures: Should Armenia change its Constitution to remove any possible claim over Nagorno-Karabakh?

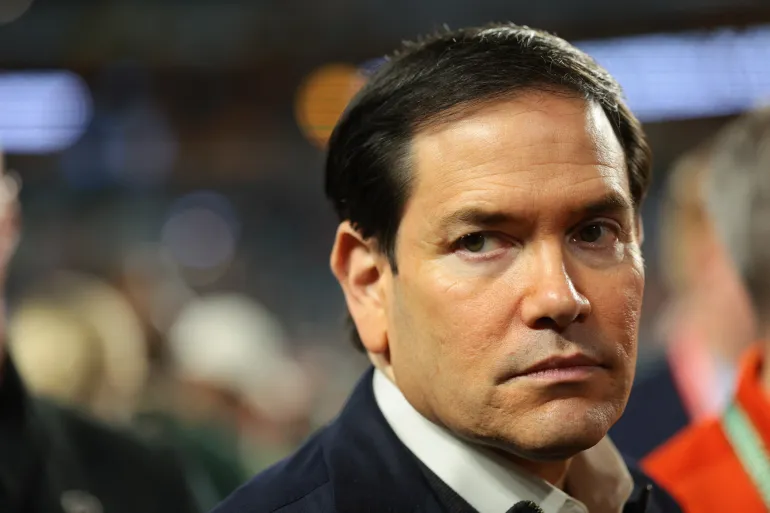

Former US ambassador Matthew Bryza, Managing Director for Straife, Board Member of the Jamestown Foundation, Former Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for Europe and Eurasia, — who’s watched this file for decades — puts it bluntly:

“Azerbaijan’s demand that Armenia amend its Constitution to eliminate any ambiguity that Nagorno-Karabakh and its seven surrounding Azerbaijani regions (now termed collectively by Azerbaijan as ‘Karabakh and East Zangezur’) constitute Azerbaijani territory is the final major obstacle to Azerbaijan and Armenia finalizing their peace treaty.”

He also notes that Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan has already floated the idea in public:

“The two countries’ foreign ministers initiated the text of that treaty under US President Donald Trump’s supervision in the White House in Washington on August 8. The two countries had finalized that text in March of this year. Prime Minister of Armenia Nikol Pashinyan has publicly called for Armenia’s Parliament to accept and ratify such a constitutional amendment, suggesting he does not view this Azerbaijani demand as unacceptable or unreasonable.”

So why is this so contentious—and why now?

This isn’t a fight over a single word; it’s about Armenia’s founding documents. The preamble of Armenia’s 2015 Constitution references the 1990 Declaration of Independence. Baku reads passages in (and around) that historic declaration as implying a reunification with Nagorno-Karabakh—i.e., a territorial claim on internationally recognized Azerbaijani land.

Dr. Vahram Ter-Matevosyan, Professor of History at the American University of Armenia, lays out the core of the dispute:

“The essence of the issue is as follows: the Declaration of Independence of the Republic of Armenia, adopted on August 23, 1990, is considered the birth certificate of Armenia’s Third Republic. In essence, Azerbaijan’s problem is not about specific chapters or articles in Armenia’s Constitution, adopted on July 5, 1995, then amended in 2005 and 2015, but its preamble, which refers to the Declaration of Independence as a document that enshrines “the fundamental principles of the Armenian Statehood and the nationwide objectives.” According to Azerbaijan’s interpretation, the preamble of the 1990 Declaration proclaims the reunification of the Armenian SSR and Nagorno-Karabakh. Hence, Baku reads it as an explicit territorial claim against it, which is present in the preamble of Armenia’s constitution. In fact, that provision of the Declaration, unlike the other objectives, was never realized, as Nagorno-Karabakh declared its independence on September 2, 1991.”

From Baku’s vantage point, deleting that ambiguity would close a chapter; from Yerevan’s perspective, who asks for the edit matters almost as much as what is edited.

“The people of Armenia oppose changing the Constitution at Azerbaijan’s demand because they see it as humiliating and perceive it as another concession to Azerbaijan’s long list of preconditions—concessions for which Armenia receives nothing essential in return, while Azerbaijan gains everything and continues to impose new demands. Azerbaijan’s rhetoric does not inspire trust and confidence among the Armenian public and political opposition.”

Ambassador Bryza adds a dose of political reality about why it’s hard to pass—even if leaders want the peace:

“Amending Armenia’s Constitution is proving politically difficult, as many in Armenia still hold out hope for reversal of the outcome of the Second Karabakh War and Azerbaijan’s September 2023 operation, which resulted in the disbanding of the ethnic Armenian separatist authority and the unfortunate flight of over 100,000 ethnic Armenians from Khankendy/Stepanakert.”

Under Armenia’s 2015 basic law, changes to constitutional architecture (and anything touching the preamble and foundational principles) require super-majorities in Parliament and often trigger a national referendum. In plain terms: even if Pashinyan’s ruling party can pass the first gate, the public likely gets a say—raising the stakes and the temperature.

Dr. Ter-Matevosyan’s political forecast is straightforward:

“If Prime Minister Pashinyan succeeds in concluding and signing the peace treaty before June 2026, when the next parliamentary elections are scheduled, his party will face no obstacles in ratifying it, as it holds the necessary parliamentary majority.”

A ratification vote on a treaty and a popular vote on a constitutional edit, however, are not the same. Recent polling suggests the ground is rocky: a survey by GALLUP International’s Armenia office puts support for constitutional change as low as 12%. Even if that number moves upward in a campaign, it shows how steep the hill is.

Pashinyan argues publicly that the case for a new constitution isn’t about bowing to Baku but about legitimacy—refreshing a text that Armenians “own.” Many voters, though, hear something else: a neighbor dictating their basic law. That’s a hard sell in any democracy, let alone one emerging from a traumatic war.

The Armenian Apostolic Church is another powerful variable. It doesn’t oppose “peace” as a concept; it warns about the conditions for peace.

“The Armenian Apostolic Church remains one of the most trusted institutions in the country. With more than 1,700 years of continuous existence, it is a cornerstone of Armenian identity… Importantly, the Church does not directly oppose Pashinyan’s peace initiatives; rather, it has been vocal about the conditions under which peace should be pursued—a crucial distinction. The fall of Artsakh, with the loss of around 400 churches, dealt a profound blow to the Church’s historical and spiritual presence,” says Dr. Ter-Matevosyan.

Government–Church tensions (including arrests of senior clergy and public spats with the Catholicos) have polarized the landscape further, creating a rallying point for conservative and nationalist critics who view any constitutional edit as capitulation.

Opposition parties, meanwhile, brand the edit as the start of a slippery slope: today the preamble, tomorrow borders, then transit corridors. As Dr. Ter-Matevosyan sums up the sentiment:

“For critics, Azerbaijan’s list of demands is excessively large and endless. With every concession, Azerbaijan feels encouraged and emboldened to ask for more.”

If Baku’s demand truly is the “final major obstacle,” then clearing it could tip the process from initialed to signed, allowing border delimitation, transit links, and investment to follow. The U.S. and EU have both telegraphed real economic and political upside once the deal is sealed.

Leaving a disputed clause in a founding document is like storing a legal grenade in your basement. Precise language reduces future pretexts for crisis.

Yerevan would gain leverage with Western partners by fixing an issue many in Europe and the US quietly view as a stumbling block. That can translate into money, security assistance, and—critically—guarantees that reduce the risk of renewed conflict.

Constitutions are not bargaining chips. Editing yours because a counterpart demands it looks—and feels—like coercion, which undermines the domestic legitimacy any peace deal needs.

If the public believes the price of quiet with Baku is an open-ended series of constitutional, legal, and policy “tweaks,” support will crumble fast. That’s the core of the trust deficit.

A referendum could become a proxy war over identity, church–state relations, and the government’s overall record—rather than a cool-headed vote on a preamble clause. Lose that referendum, and you don’t just slow the peace train; you derail it.

International reaction has been mixed. The European Parliament has explicitly called for accelerating normalization and talks up more financial/technical support to harden peace and counter interference. Brussels wants legally clean borders and fewer ambiguities before opening the bigger taps. Washington welcomed the August 8 step and has cast the pending treaty as a “historic” chance to close a violent chapter. The message between the lines: remove obstacles—legal and political—fast.

Turkey has been publicly supportive of normalization but is still slow-rolling the full opening of the land border and diplomatic ties—creating skepticism in Yerevan about promised regional dividends.

Persistent questions about the terms/status of any transit route linking Azerbaijan proper with Nakhchivan keep Tehran wary of a deal that shifts regional trade corridors. Russia feels marginalized—with frayed ties to both Baku and Yerevan. That doesn’t necessarily mean Moscow will blow up the process; it does mean it has fewer incentives to help it along and more opportunities to meddle if things wobble. Dr. Ter-Matevosyan says:

“Armenia’s ruling party is striving to advance its agenda of peace, yet not all regional actors are engaging in good faith… For Armenia, the path forward remains long and uncertain. Many elements of the current arrangements lack clarity and are not openly discussed — an open invitation for many stakeholders to spoil or undermine the path to peace. This ambiguity is critical, as past experience demonstrates that significant agreements often remained incomplete or unimplemented precisely because essential details were overlooked.”

Constitutional edits are never just about words; they’re about identity, security, and power. Armenia can probably carry a tightly scoped change if it’s paired with visible reciprocity, tangible benefits, and external guarantees that feel real to ordinary voters. But if the change looks like a one-way street—“you amend, we wait”—expect a backlash that could set the entire peace track back years.

The latest news in your social feeds

Subscribe to our social media platforms to stay tuned