In a lab tucked inside the University of Wyoming’s Agriculture Building, a group of molecular microbiologists may have found a sweet new ally in the fight against tooth decay: maple.

Professor Mark Gomelsky of UW’s Department of Molecular Biology says the finding came out of years of work on Listeria, a dangerous food-borne pathogen.

“It was one of those lucky situations where you think, this is how it’s going to work—and it works just like that,” he told Wyoming News Now.

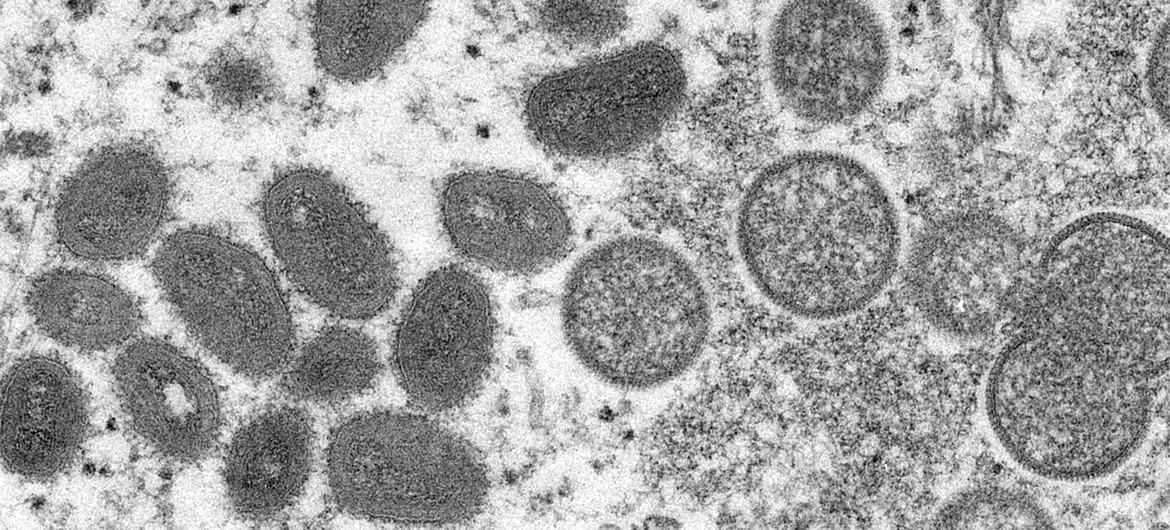

Here’s the gist. The cavity-causing bacterium Streptococcus mutans sticks to your teeth by using an enzyme called sortase A—that’s the glue that helps it build stubborn biofilms (plaque). According to a UW press release, polyphenols found in maple (and also in green tea) jam that enzyme, making it far harder for S. mutans to latch on in the first place.

“It’s not that nobody’s ever looked at sortase before,” Gomelsky said. “What’s distinct here is the compounds we found are benign—they’re edible.”

The research, published in August in Microbiology Spectrum under the title “Maple polyphenols inhibit Sortase and drastically reduce Streptococcus mutans biofilms,” turns a lab insight into something that could soon show up in your medicine cabinet. Gomelsky says the team is already working on practical uses.

“It’s not very often that discoveries made in research labs have almost immediate applications,” he said.

Think mouthwash, toothpaste—or even kid-friendly lollipops formulated to be tough on plaque and gentle on everything else. A new company—“May Pall,” as Gomelsky described it—has been formed to help move the science from petri dish to product.

A quick reality check: the results so far come from controlled lab studies, not clinical trials. But for now, Wyoming’s latest export might be more than horses and high plains—the state could add maple-powered smiles to the list.

The original story by for Wyoming News Now.

The latest news in your social feeds

Subscribe to our social media platforms to stay tuned