EXCLUSIVE: Lessons of the Past. Political Violence in America, from the 1960s to the 2020s.

A memorial for Charlie Kirk is seen at Utah Valley University in Orem, Utah on Sept. 13 (Chet Strange / Getty Images)

Political violence has always lurked beneath the American experiment. At moments of upheaval, it bursts into the open—assassinations, riots, bombings, and now live-streamed attacks by men radicalized online. From the 1960s to the 2020s, the cast changes, the media changes, but the core themes keep returning: backlash to social change, racial and cultural fear, and the idea that violence can send a political message when words seem to fail. Lining up today’s headlines against the tragedies of the past, the echoes — and the differences — are instructive.

On September 10, 2025, conservative activist Charlie Kirk was shot and killed during an outdoor event at Utah Valley University in Orem. Utah’s Republican governor Spencer Cox called it “a political assassination.” Within 48 hours, police arrested a 22-year-old suspect; authorities said he held “deep disdain” for Kirk’s views and had indicated responsibility to a family member. UVU launched an independent review of campus security. Candles, vigils, and wall-to-wall conservative media tributes followed.

David J. Garrow, Pulitzer Prize-winning author of ‘Bearing the Cross’ and ‘Rising Star,’ the definitive pre-presidential biography of Barack Obama, called the killing “phenomenally astonishing,” adding:

“The scale of reaction to his assassination is greater than anything we’ve seen in this country with any individual killing since the George Floyd murder in Minneapolis. The reaction to this, though, has been much more affirmative… I’m very fearful… that this sort of politically calculated assassination may well lead to others going forward. We were very fortunate, 14-15 months ago, that Donald Trump was not killed…up in Butler, PA. We’ve seen attacks on other federal and state legislators and their families, families of federal judges, and Supreme Court Justice Kavanaugh. So there is a constant drumbeat of these killings and attempted killings, and I’m somewhat pessimistic about the short-term future.”

The fear is not abstract. Ryan Routh, charged with the 2024 golf-course attempt on Trump, was found guilty in a federal trial in Florida. Routh will be sentenced on December 18 by Judge Aileen Cannon. He faces the possibility of life in prison. House task-force deemed the earlier Butler, Pennsylvania, attack “preventable,” citing security failures.

The politics reacted in real time. Reuters and NPR tallied a sharp rise in incidents since 2020, warning about “a vicious spiral.” And in the days after Kirk’s murder, the White House moved to label “antifa” a domestic terrorist organization—a step legal scholars say the US has no clear statutory mechanism to enforce, underscoring how symbolism now collides with law.

In an interview with Wyoming Star Rick Perlstein, historian, writer, and journalist, argued we’re living through “stochastic terrorism”—violence incubated by rhetoric, not orders:

“When the guy shot up the Walmart in El Paso. He shot Mexicans. You can say he was reacting in a political way to what he had heard from Donald Trump and Fox News, that Mexicans were invading America. When the mass shooter shot the Tree of Life synagogue, he was responding to a political story that he would have heard from allies of the president and Fox News, which is that Jews were exercising the Great Replacement.”

Perlstein also pointed to an asymmetry of attention:

“The killing of Charlie Kirk has reverberated all throughout the society. The fact that the killing of politicians in Minnesota by a Trump supporter didn’t get as much attention, and it isn’t seen as the same level of terror. Melissa Hortman is barely remembered. There’s this long tradition of kind of downplaying violence from the right in America, and I think it’s very disturbing.”

Whatever the partisan framing, the civic texture is undeniable: armed men at rallies, families of judges and legislators targeted, and death threats flooding inboxes. As Perlstein put it:

“It’s like nuclear deterrence… You don’t have to use nuclear weapons. It’s just the threat of using them that gets things done.”

Was it different in the 1960s? Short answer: yes and no. The 1960s were drenched in violence, but the cast of characters and state response looked different.

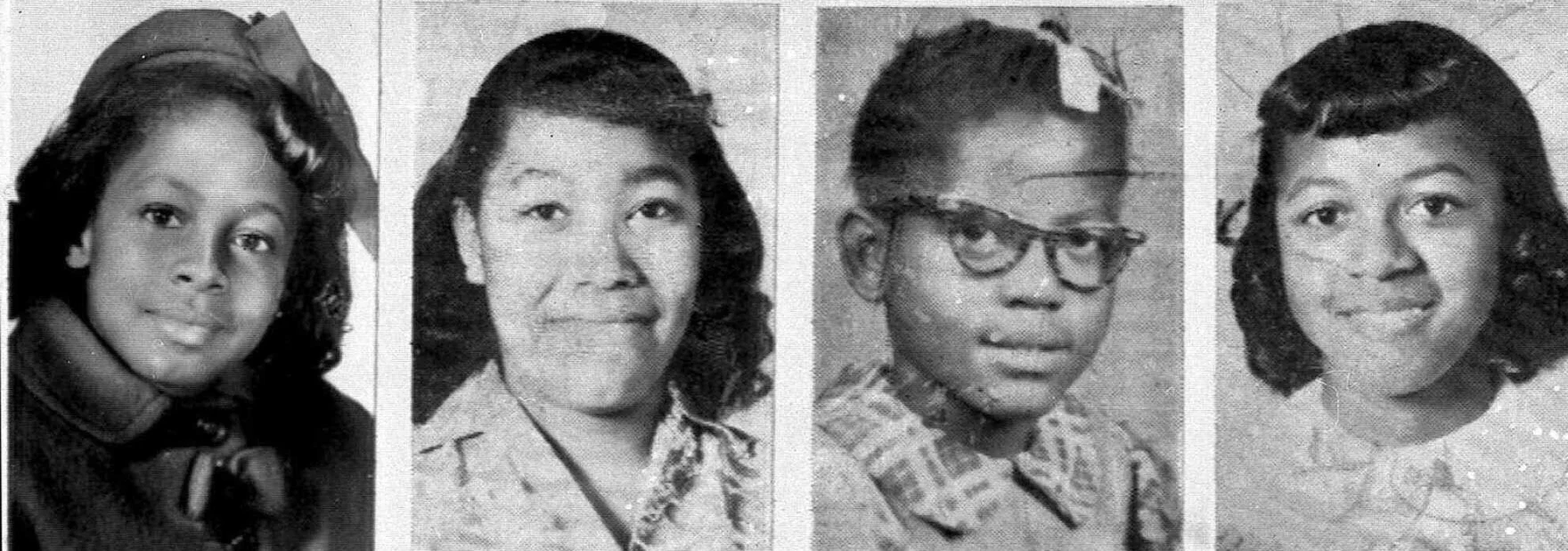

On the right, segregationist terror scarred the South. Birmingham was nicknamed “Bombingham.” The 16th Street Baptist Church bombing on September 15, 1963 — dynamite planted by Ku Klux Klan members — killed four girls and shocked the nation. Survivors and families still mark the anniversary as a turning point that helped galvanize the Civil Rights Act.

From left, Denise McNair, 11; Carole Robertson, 14; Addie Mae Collins, 14; and Cynthia Wesley, 14, were killed in the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church, in Birmingham, Ala., on Sept. 15, 1963 (AP)

Garrow emphasized how law enforcement complicity enabled much of this terror:

“In those years you had a repeated pattern of Southern law enforcement complicity in some of the killings, most notoriously in Mississippi. While there was always tension, whether within the Birmingham Police Department or the Alabama State Troopers, similarly, in Georgia, between honest cops and Klan cops.”

Perlstein added:

“The accountability was systematically occluded by the institutions of justice. Things like jury nullification — the jury not convincing people, even if the evidence was against them. In the murders of the civil rights workers, the Klan had been tipped off by the county sheriff.”

Beyond the Klan, paramilitary militias emerged. The Minutemen, a 1960s anti-communist organization led by Robert DePugh, stockpiled weapons and trained for a coming internal war; they later featured heavily in FBI files and academic studies of the “paramilitary right.”

On the left, violence also flared. The Weather Underground, a splinter from Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), carried out symbolic bombings of government sites. The Black Panthers practiced armed self-defense; by the early 1970s the Black Liberation Army carried out targeted attacks on police. Garrow’s summary:

“As we move into the 1967-68 period, both some veterans of the Southern Black Freedom Struggle and more folks from the urban north lose patience with nonviolence. Stokely Carmichael, who came out of SNCC and then left SNCC, is an especially tragic representative of that. Someone who had immense potential and charisma and really sort of spun out from 1968 onward. Rather than potentially becoming a greatly influential voice, he ends up as an utterly marginalized exile living in a West African military dictatorship. It’s similarly sad what happened to dozens of the white student radicals, who came out of SDS and then went into these different manifestations of the Weather… and ended up… blowing themselves up with bombs they were trying to make, doing symbolic or attempted bombings in toilets at the Pentagon or the Capitol. It was dangerous. Some people were killed. But the political pointlessness of it, the fundamentally self-destructive nature of it, is what, to my mind, ends up most distinguishing all of that.”

Perlstein insists right-wing violence is chronically minimized in memory. Exhibit A: the Hard Hat Riot (New York City, May 8, 1970), where construction workers and office clerks beat anti-war protesters after Kent State — and then Nixon invited the union leaders to the White House and posed with a gifted Commander-in-Chief hard hat.

“This idea is very different from left-wing violence, which never really had any sanction from public officials. You had this kind of winking, assertion of complicity on the part of the highest levels of the government sometimes,” said Perstein.

Meanwhile, the FBI saturated both Klan klaverns and left groups with informants. The bureau penetrated white supremacist outfits comparatively effectively; it struggled more with decentralized violent leftists. Later, the Church Committee exposed abuses, including selective dirty tricks under the COINTELPRO banner — but the larger machine mostly churned out paperwork and penetrations, not omnipotent conspiracies. Garrow explained the nuance of the FBI’s position:

“The FBI was basically an information-collecting organization. An agency that really majored in the production of paperwork… Aside from a modest number of purposefully harmful attempts to manipulate or hamstring groups, the FBI was 99% a reactive organization. The single worst thing the FBI did, to use the intelligence term, was “snitch jacketing” — which means falsely painting a totally loyal organization member… as an informant, i.e., a ‘snitch’, in an attempt to protect and deflect attention from the real informants… COINTELPRO was run by one single supervisor, a man named David Ryan. So it was not a large-scale operation. It was episodic… It was definitely harmful in a number of instances. But it’s also, at bottom, pretty Mickey Mouse. The FBI’s mindset was to perceive anything on the activist left or anything on the activist right as a threat to government control of the social order… Almost everything that the FBI did was known to and at the behest of successive US presidents… Senator Church, half a century ago, used the phrase “rogue elephant” to discuss the intelligence community, the CIA in particular. But with both the CIA and, even more so, the FBI, the bad things they were doing were not secret, not rogue. They were known by the President of the United States.”

The decade’s violence was punctuated by assassinations that rewired the national psyche:

- John F. Kennedy (1963) — murdered by Lee Harvey Oswald, a troubled loner.

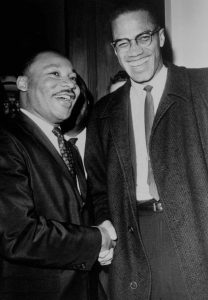

- Malcolm X (1965) — killed by members of his former organization, the Nation of Islam.

- Martin Luther King Jr. (1968) — assassinated by James Earl Ray, a racist hoping for reward money.

- Robert F. Kennedy (1968) — shot by Sirhan Sirhan during the presidential campaign.

Garrow stayed cautious in his assessment:

“The 1960s assassinations don’t really create a pattern. JFK is killed by one oddly imbalanced individual, Oswald. Malcolm X, who should be ranked of the same importance as Dr. King, was killed at the orders of his own former organization, the Nation of Islam. Dr. King was killed by a white racist who thought he might be financially rewarded for it through what he’d heard from his family members in St. Louis. And then RFK, lastly, like his brother, is killed by a somewhat imbalanced loser.”

Perlstein focused on the psychological blast radius:

(Henry Griffin / AP)

“The fact of the assassination increased polarization, paranoia, and inter-community distrust. The JFK assassination… really was… ‘a loss of innocence’… Things like settling political issues due to violence were not seen as an American thing… Where did this violence come from?… The investigations were deeply distrusted and created this culture of paranoia and suspicion and conspiracy… In the case of Martin Luther King… it made it very hard for Black people and white people to work together for justice… It really discredited King’s doctrine of nonviolence, nonviolent civil disobedience… In the case of the Malcolm X assassination, it caused just an enormous amount of distrust between different factions in the Black movement… All these assassinations really did reverberate and created a fundamental sense that the norms of society were breaking down, and that, of course, licenses the breaking of norms. So left-wing movements become enormously more militant. The idea that working peacefully through the system doesn’t work… The vision of Martin Luther King, which was, “Bear the blows of the enemy in a spirit of loving-kindness, and put his cruelty on display, and appeal to people’s conscience,” was replaced by a doctrine of Black power, which talked about armed self-defense, and there was a semiotics of violence.”

His concrete example: Stax Records, a soul record label in Memphis — once a proud interracial enterprise — fell apart after King’s death as mistrust consumed the workplace.

Garrow explained the depths of the damage to nonviolent action:

“Dr. King was deeply, totally committed to nonviolence because of his own deep grounding in religious faith. People may read that King was influenced by Mohandas Gandhi and other earlier advocates and practitioners of nonviolence. But those were add-ons for Dr. King’s grounding in a Christian Baptist church-based faith. That’s what created who he was… That faith in nonviolence was taught and practiced all across the Southern Movement, from 1955 up through at least 1965. Malcolm… came out of a totally different northern urban background and environment. Once he split away from the Nation of Islam, you saw Malcolm moving beyond a narrow Black nationalism to a strong pro-Black perspective… Malcolm’s killing in February of 1965 was terribly tragic, because he had his best years all ahead of him. By the time that Dr. King was killed in April of 1968, Dr. King was a very tired, emotionally almost wasted person, because his life over the preceding 12-13 years had been so endlessly demanding and draining and exhausting. So I regret the loss of Malcolm’s potential, especially.”

The lesson: assassinations don’t just remove leaders; they decimate coalitions and shift strategy.

What truly distinguishes the 2020s is the atomized perpetrator — often an ideological grab bag, nursing grievances in online subcultures, and performing for an audience that platform algorithms help assemble.

Garrow sees a bleak digital accelerant:

“I view smartphone and social media addiction as something that’s having an extremely deleterious effect and leads to people spinning out in potentially dangerous, deadly ways… People who had some sort of conspiratorial fantasy about the CIA or any number of things had to actually write it out and get a stamp to express themselves. I still have hate mail letters that I received in the 1990s from one of James Ray’s brothers, the assassin of Dr. King… The internet and social media allow people who are emotionally disturbed to have a potential listenership that is thousands-fold larger than was possible any time prior to these last 25 years. The Kirk assassin seems to have lived a significant portion of his recent life in these sorts of gamer channels. This is not something I’m at all knowledgeable about. But there’s a lot of self-inflicted damage going on out there among younger people. That’s my sad conclusion.”

Perlstein points the finger at engagement economics:

“Conflict glues more eyeballs to screens than cooperation… Writing programs that privilege conflict over cooperation — ‘Hate over love,’ if you will — has had a terrible underlying role in activating the centers in people’s brains that make them fearful and hateful. And, more likely to commit violence.”

Research on digital subcultures and aestheticized violence backs this up: online milieus merge nihilism, irony, and spectacle, encouraging imitative behavior among isolated men. Investigations by Reuters describe a new “grab-bag extremism”; academic work traces the shift from coherent organizations to meme-driven, self-styled shooters; and GNET scholars warn how “ideological nihilism” mingles with internet aesthetics to produce action for action’s sake.

That helps explain why post-2020 violence can feel less negotiable than in the 1960s. You could infiltrate a Klan klavern or flip a Weather operative; you can’t bargain with a broadcast-seeking loner whose only demand is to be seen.

Violence is cyclical when identity and status feel threatened. In the 1960s, civil-rights breakthroughs, desegregation, and anti-war protests collided with white backlash and Cold War panic; in the 2020s, demographic change, gender and racial politics, and post-truth media form a similarly volatile brew. Comparative studies and polling show small minorities of partisans deem threats — or even violence — acceptable; that minority is still enough to keep society on edge.

State signals matter. The Hard Hat Riot moment — rioters feted in the Oval Office — illustrates how elite winks and nods can legitimize violent actors. Today’s legally dubious “terrorist” labels for decentralized domestic movements send their own signals, even when courts and statutes don’t support them.

Assassinations destabilize more than movements. From King to Kirk, killing leaders doesn’t just silence a voice; it shifts norms and strategies, deepens paranoia, and tempts imitators. After Kirk’s murder, experts warned of a copycat effect; after King’s, even biracial cultural spaces unraveled.

Technology changes radicalization. The 1960s had mimeographs, newsletters, and clandestine meetings; 2020s attackers are incubated by feeds, livestreams, and algorithmic amplification. That doesn’t create violence by itself, but it speeds it, scales it, and helps script it.

Nonviolence still works. The civil-rights movement’s disciplined nonviolence won durable legitimacy; the Weather Underground’s bombs alienated would-be allies. That tradeoff hasn’t changed. As Garrow put it of King, the commitment wasn’t tactical alone — it was moral and religious, and therefore sustainable.

The hardest truth is also the simplest: America has never been free of political violence. What changes is its form — from church bombings to viral videos, from hard hats to hashtags. The question for the 2020s isn’t whether violence exists; it’s whether we normalize it — or recommit to a politics sturdy enough to contain it.

The latest news in your social feeds

Subscribe to our social media platforms to stay tuned