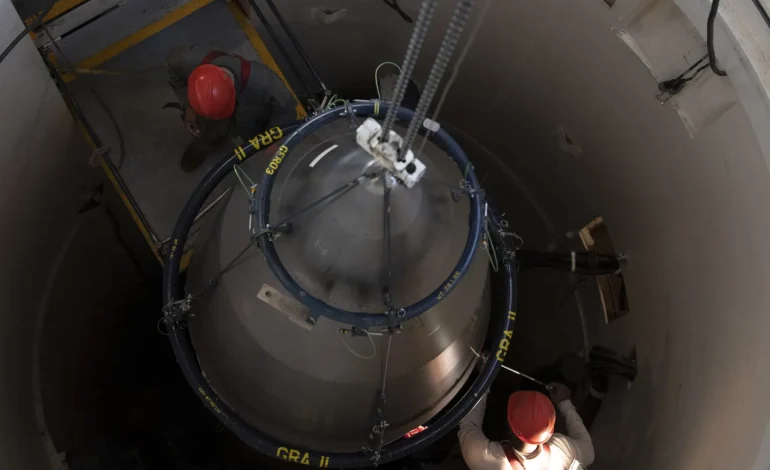

Wyoming is about to be the test bed for the biggest overhaul of America’s land-based nuclear force in decades. F.E. Warren Air Force Base in Cheyenne, which commands 150 missile silos spread across the region, is slated to go first as the US swaps out aging Minuteman III missiles for the new Sentinel system. Think new comm towers, fresh fiber-optic runs, and a wave of construction on and off base. Also think delays, blown budgets and a lot of disruption for ranchers, towns and taxpayers.

This is the part where the Pentagon’s timeline meets reality. The plan had been to start replacing Cold War-era Minutemen in Colorado, Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota and Wyoming in time to be finished by 2029. Now the first Sentinel fields may not be ready until 2033. Matt Korda of the Federation of American Scientists calls Wyoming the “guinea pig” — the first place the Air Force will learn hard lessons it hopes to apply later in Montana and North Dakota. In the meantime, the Minutemen’s lives are being extended because the new missiles aren’t ready.

The money is slipping, too. The program’s acquisition cost has jumped roughly 81% from an estimated $77 billion in 2020 to around $140 billion, triggering a Nunn-McCurdy breach — Washington-speak for “you’ve gone so far over budget Congress and the Pentagon must re-justify the whole thing.” Korda’s bottom line is blunt: those overruns ultimately show up in the lives of people who live near the silos and in the tax bills of people who don’t.

Part of the problem is the infrastructure. The Air Force initially hoped to reuse a lot of the 1970s silo network to save time and cash. That turns out to be largely impossible. New cabling corridors have to be dug. New easements have to be acquired. That means real farmers and ranchers sitting across the table from federal land agents. The service says it will offer fair market value, but history suggests many owners will have little practical choice if their parcel is where the conduit needs to go.

The construction footprint will be enormous. Expect new facilities on base in Cheyenne and a swarm of off-base projects to support the missile fields. A major workforce hub is planned for nearby Kimball, Nebraska, bringing an estimated 2,500 to 3,000 workers. The Air Force’s own environmental impact statement doesn’t sugarcoat the ripple effects: tighter housing and higher rents, pressure on schools and services, more noise and traffic, and ecological impacts — all of it landing over a three-to-five-year buildout that’s already beginning.

How much say do locals have? Some, but not much. There are hotlines and town halls, and the Air Force has started sending letters to landowners around F.E. Warren about new easements. But this is a “too big to fail” program with decades of momentum behind it. In the 1960s, communities learned that missiles got sited where the Air Force needed them, even if that meant plunking a silo within sight of a family home. Officials say they’ve learned from that era; residents will soon see what that means in practice.

All of this is happening as every nuclear-armed country is modernizing. The US still relies on its triad of submarines, bombers and land-based ICBMs, and Wyoming sits at the heart of that last leg. If the Sentinel program stays on course, those buried launch sites will be part of America’s arsenal for another half-century. Supporters argue that visible, dispersed ICBMs deter adversaries and limit damage in a doomsday scenario. Critics counter that the price tag is staggering, the timelines are optimistic, and living among missile fields makes communities a target whether they like it or not.

For now, the takeaway is simple. Wyoming goes first. The schedule is slipping. The bill is rising. And the “lessons learned” here will shape what happens next in Montana and North Dakota — along with what everyday life looks like across the High Plains while America rebuilds its nuclear backbone.

The original story by

The latest news in your social feeds

Subscribe to our social media platforms to stay tuned