Armenia and Azerbaijan: A “Newborn Peace” With Old Questions

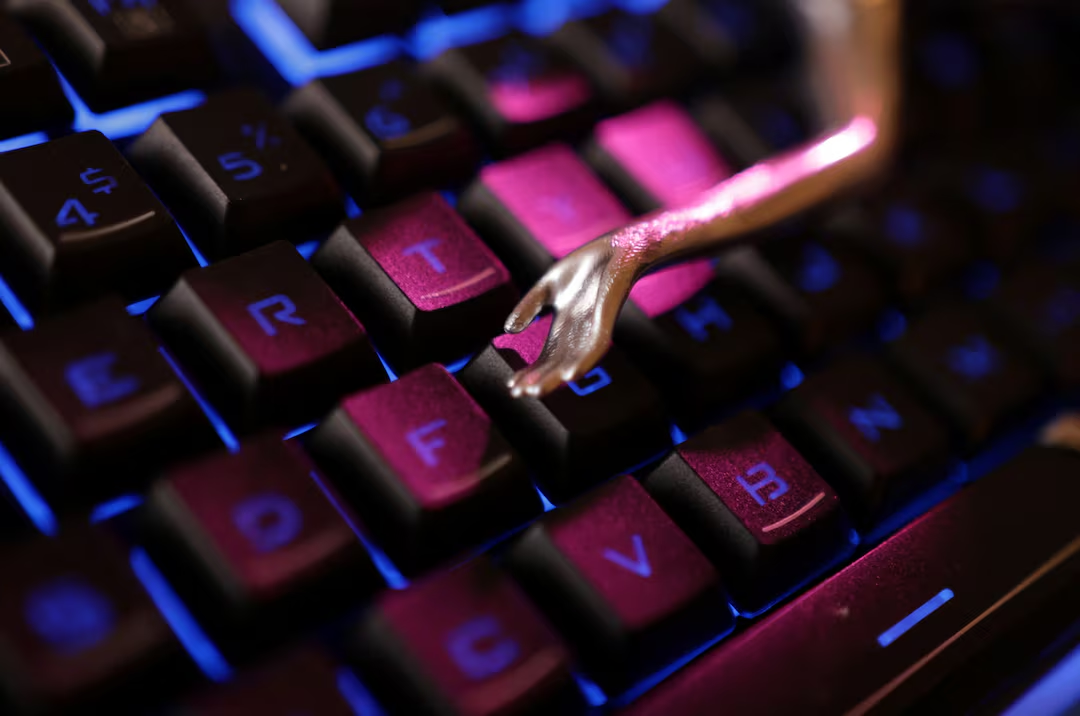

Armenia and Azerbaijan are, at least on paper, in a very different place than they were just a year ago. In August, Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan and President Ilham Aliyev stood in Washington with Donald Trump and signed a declaration affirming that peace between their countries was not only possible but underway. Pashinyan has leaned heavily into the metaphor since: peace as a “newborn” that must be cared for daily if it is to survive.

It sounds hopeful. But scratch beneath the surface, and the picture is far more complicated — full of constitutional disputes, geopolitical jockeying, and the looming question of what exactly a so-called “Trump Route” across southern Armenia might mean.

At the Council of Europe in Strasbourg, Pashinyan positioned Armenia as a committed member of the democratic club. He called the Council of Europe “our home” and argued that the institution isn’t foreign to Armenia but an extension of its statehood. He framed democracy, human rights, and judicial reform not as boxes to tick for Brussels but as existential tools for a fragile peace.

European officials welcomed this message, while Washington has been quick to brand the August declaration as proof that Trump personally unlocked a historic breakthrough. Pashinyan himself has publicly credited Trump for the momentum, insisting the White House meeting was the decisive push. That framing, though, puts the US squarely in the driver’s seat of a process that has plenty of other stakeholders—including Russia, still watching from the wings.

One of Baku’s favorite pressure points has been Armenia’s Constitution, which, according to Azerbaijani officials, contains veiled territorial claims. Pashinyan is now pushing back hard. He reminded PACE that Armenia’s Constitutional Court already ruled last year that the bilateral border delimitation documents don’t contradict the Constitution. He also pointed out that both the draft treaty and earlier European-brokered declarations commit both sides to respect the 1991 Alma-Ata Declaration—the Soviet breakup treaty that locked borders in place.

In practice, that means the treaty itself would override any ambiguity in Armenian domestic law, since once ratified it carries “higher legal force.” Pashinyan’s bottom line: there is no legal obstacle to peace. The bigger issue, he argued, is political trust. Armenians don’t fully believe in their Constitution because of decades of rigged referendums and manipulated amendments. That, he says, is why Armenia eventually needs a new Constitution — but not to satisfy Azerbaijan, rather to restore legitimacy at home.

Then there’s the murky business of regional connectivity. Russia’s ambassador to Yerevan recently confirmed Moscow is open to consultations about the so-called “Trump Route” — a transport corridor across southern Armenia meant to link Azerbaijan to its exclave of Nakhchivan and beyond to Turkey and Iran.

Right now, the project is little more than an idea. As Russia’s envoy Sergei Kopyrkin put it, details about cargo regimes, passenger rights, and security guarantees “still need to be agreed upon.” But the fact that Moscow is talking openly about it suggests the corridor is already part of the bargaining mix. The catch? Armenia’s borders are still guarded in places by Russian troops, and the country is a member of the Moscow-backed Eurasian Economic Union. That means every mile of the “Trump Route” will be as much about geopolitics as about asphalt and rail.

For all the lofty talk, the hard realities of the Armenia-Azerbaijan conflict remain. There are still missing persons from past fighting, prisoners on both sides, and communities deeply scarred by decades of mistrust. Pashinyan has been clear that these humanitarian issues need answers if peace is to take root.

And then there’s the larger geopolitical context. The EU and US are backing peace and reform. Russia says it supports any normalization efforts but clearly wants a hand on the wheel. Iran, too, has a stake in how regional transit lines are drawn. Each outside actor brings leverage but also baggage.

So while Armenia’s prime minister speaks warmly of democracy’s “home” in Europe and peace as a newborn child, the regional chessboard looks far less tender. For peace to mature into something durable, Yerevan and Baku will have to show they can build trust not just under Trump’s signature or Europe’s applause, but in the day-to-day grind of governance, security guarantees, and compromise.

For now, what exists is an agreement on paper, a constitutional debate that seems legally settled but politically raw, and a corridor project that is more slogan than reality. In the South Caucasus, that still counts as progress — but it’s fragile progress that could topple as easily as it was declared.

The latest news in your social feeds

Subscribe to our social media platforms to stay tuned