Yerevan is once again showing signs of political turbulence. The rise of the “Po-Nashomu” (“Our Way”) movement, led by the detained tycoon Samvel Karapetyan and coordinated by his nephew Narek, has become a mirror of the growing public exhaustion with Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan’s government.

At a recent congress in the capital, Narek Karapetyan announced that over 5,000 volunteers had joined the movement in just six weeks.

“If our numbers keep growing at this pace, we’ll soon be tens of thousands strong,” he told supporters. “With Samvel Karapetyan’s ideas and programs, we will make Armenia a model country.”

It’s a bold promise, one that resonates precisely because Pashinyan’s administration, after years in power, seems unable to contain the social and political discontent simmering across the country.

Samvel Karapetyan has been in detention for more than 110 days, accused of “calls for a coup” after vowing to defend the Armenian Apostolic Church from what he described as government attacks. His imprisonment, much like the earlier cases against outspoken clergy such as Archbishop Mikael Adjapahyan, has deepened a sense that the government now sees moral authority itself as a threat.

In a message from prison, Karapetyan told his followers:

“We will not retreat, we will not stop, and we will make Armenia the most prosperous and happy country, we will do it our way.” That defiant tone has clearly struck a chord with parts of society tired of Pashinyan’s political style, one built on revolution but sustained by confrontation.

Meanwhile, the movement is evolving fast. Plans are underway to transform “Po-Nashomu” into a formal political party by January, with promises to name a prime ministerial candidate who will “meet the expectations of all Armenians.” The group also insists it will not ally with the old-guard blocs of former presidents Robert Kocharyan and Serzh Sargsyan, signalling an effort to brand itself as a generational alternative rather than just another oligarchic project.

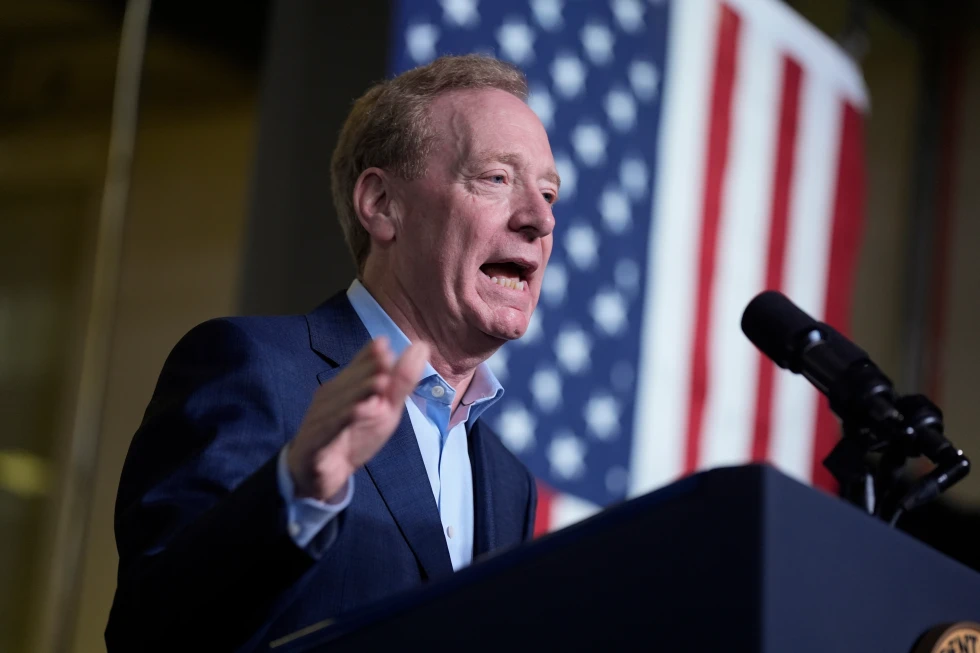

Economist Daron Acemoglu, the Armenian-born Nobel laureate who joined as a consultant, urged Armenia to focus on digital innovation and AI development.

“Artificial intelligence can become the driving force of Armenia’s economic progress,” he said, while also warning that Pashinyan’s government’s approach to nationalisation and property rights “sends the wrong signal to investors.”

Yet the broader picture goes beyond economics. The arrests of church officials, including Bishop Mkrtich Proshyan, nephew of Catholicos Garegin II, mark a dangerous escalation in the standoff between the state and one of Armenia’s oldest institutions. The government now routinely frames dissent as subversion.

At the same time, international developments add more weight to Armenia’s fragile internal balance. The United Kingdom’s recent decision to lift its decades-old arms embargo on Armenia and Azerbaijan, justified as support for “sovereignty and territorial integrity,” has only reinforced the perception that the South Caucasus is once again turning into a geopolitical chessboard. And yet, Yerevan seems too absorbed in its internal rivalries to define a coherent foreign strategy.

In this atmosphere, Pashinyan’s government looks increasingly isolated, both from parts of its own population and from the institutions that once gave it moral legitimacy. The revolution that began with calls for transparency and accountability now appears to be defined by fear and control.

Behind the slogans about progress and reform, the reality is harder to ignore: Armenia’s political system is fragmenting, its institutions are under strain, and its leadership is losing the confidence it once enjoyed. The cracks are no longer subtle, they’re widening with every arrest, every protest, every speech that promises “prosperity” but delivers division.

The latest news in your social feeds

Subscribe to our social media platforms to stay tuned