EXCLUSIVE: Inside China’s Rare-Earth Restriction Crisis

Beijing just tightened the spigot on the obscure metals that run modern militaries. Washington’s choices over the next 6–18 months will decide whether this becomes a supply squeeze — or a full-blown national security crisis.

Samples of rare-earth minerals from Baiyun’ebo or Bayan Obo mining district are on display at the Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences (IGGCAS) on May 17, 2025 in Beijing, China (VCG / AP)

For years, China supplied most of the world’s rare-earth oxides and nearly all of the separated materials and finished magnets that make smart weapons, radars, aircraft actuators, and secure comms work. That leverage is now policy. On October 9, 2025, Beijing expanded export controls on rare earths and downstream equipment, with special scrutiny on defense and semiconductor end-uses and new licensing hurdles (and denials) for foreign military users. Markets noticed immediately.

Analysts at CSIS say these are the toughest controls yet, reaching deeper into the magnet supply chain and signaling that even “trace Chinese content” could trip licensing — an extraterritorial flavor that mirrors Western tech controls on chips. Beijing is also tightening oversight of research collaboration and re-export of China-origin gear used in rare-earth recycling and processing. Translation: end-runs get harder, paperwork gets slower, and uncertainty rises.

Why now? The timing coincides with a new tariff round: the White House floated 100% tariffs on broad categories of Chinese goods, citing the rare-earth squeeze among the triggers. China has defended its curbs as “legitimate,” framed around national security, while hinting that “cooperative” buyers will still get licenses. Still, the G7 publicly aligned on diversifying supply, underscoring how concentrated these chains remain.

A week later, the rhetorical temperature eased a notch — President Trump said such tariffs are “not sustainable” even as he blamed Beijing’s rare-earth move and confirmed plans to meet Xi Jinping. But the underlying fight — over who controls permanent-magnet inputs — hasn’t cooled.

Chatham House put it bluntly: China’s new curbs are a stark warning — either the West builds resilience fast, or it accepts periodic supply shocks that shape both industrial policy and geopolitics. Al Jazeera’s explainer on October 10 connected the dots: tightened controls give Beijing leverage heading into talks and complicate US defense planning.

Rare earths aren’t optional in modern defense — they’re baked into guidance kits, seekers, AESA radars, electric actuators, quieting technologies, and secure comms. CSIS estimates that each F-35 contains ~427 kg of rare earths; a Virginia-class submarine can embed ~4.2 metric tons, much of it in high-coercivity permanent magnets (NdFeB with dysprosium/terbium) needed for survivability and acoustic stealth. That’s before you count munitions, satellites, and EW gear.

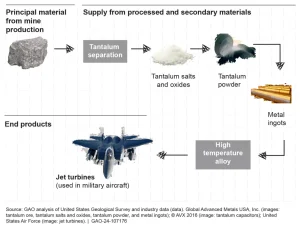

CSIS’s Gracelin Baskaran warns the magnet stage — not just mining — is the killer bottleneck; China dominates separation and magnet manufacturing, and the new rules reach into those nodes. The Pentagon has spent years seeding a “mine-to-magnet” rebuild at home and with allies, but capacity is still thin and timelines are tight.

Congressional watchdogs add a sobering angle: the National Defense Stockpile (NDS) exists for precisely this moment, yet 2024 GAO work found gaps in data and planning and a stockpile that mitigates less than half of estimated military shortfalls in base-case emergencies. The Pentagon has since moved to beef up holdings and invest via DPA Title III, but filling multi-year deficits is not a one-appropriation job.

Wyoming Star got a chance to ask Maj. Gen. (Ret.) John G. Ferrari, Nonresident Senior Fellow, American Enterprise Institute, a few pressing questions:

Wyoming Star: How exposed is the US defense industrial base to Chinese rare earths today?

John G. Ferrari: The US defense industrial base is extremely vulnerable to China’s stranglehold of rare earths; but it is even worse, because this stranglehold extends to the entire US economy. In addition to rare earths, the latest National Security Scorecard from data analytics firm Govini revealed countless China-based firms remain deeply embedded in Defense Department supply chains across 12 critical technologies.

Wyoming Star: If Beijing’s current export restrictions persist or tighten, where would you expect the first production slowdowns? What’s the realistic timeline from a rare-earth shortfall to a weapons delivery delay?

John G. Ferrari: This is very hard to predict; the US Government can prioritize rare earth usage within the US, so it will direct that the commercial sector reduce its usage first; the effects will be slow at first because the US has some limited stockpiles; but the problem is in a war, when we have to produce weapons fast, then this could cause us to run out of munitions.

Wyoming Star: Could current restrictions materially slow or disrupt US aid flows to Ukraine and other allies?

John G. Ferrari: The war in Ukraine will probably not be affected because the US has an ample supply of weapons on hand; the decision will be to use those weapons in Ukraine or save them for a potential war with China; but once depleted, it will take years to rebuild the stocks.

Wyoming Star: Where are the chokepoints in logistics and export controls?

John G. Ferrari: The chokepoints are the mining and processing of the rare earths; while mines are being developed in the US right now, this will be a problem for a long time.

Wyoming Star: What’s the role of the National Defense Stockpile? Is it sized for a multi-year geopolitical squeeze?

John G. Ferrari: The stockpile is too small and now too late to make a difference; China knows this, and that is why they are using it to extract concessions from the US.

Wyoming Star: What signals from Beijing should industry watch?

John G. Ferrari: The signals have already been sent; they are locking down the export and transshipment of rare earths to squeeze the US.

Wyoming Star: Can the US credibly de-risk defense against Chinese rare-earth leverage?

John G. Ferrari: Yes, we have plenty of rare earths in the ground within the US; we have to date chosen not to extract it or process it at scale.

That vulnerability isn’t just a geology problem. As Derek Scissors, senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), argues, America’s supply-chain failures are fixable — where we have succeeded, we’ve matched money with permitting, long-term offtake, and buy-side demand from government. Where we’ve failed, we’ve let cheap China-origin content win on price while underfunding the “boring” mid-stream.

The rare-earth squeeze is hitting just as Washington weighs a high-stakes transfer: Tomahawk cruise missiles for Ukraine. Kyiv wants them for deep-strike leverage; The Guardian notes their range (~995 miles) and cost (~$1.3 million each), and that launch options — ship, sub, or scarce land-based systems — complicate deployment.

In public, the President’s line has wobbled. Hours before meeting Volodymyr Zelenskyy, he said, “We need Tomahawks too,” signaling reluctance to part with an already-thin inventory. Ukrainian and allied outlets tracked the shift after a Trump–Putin call; US reporting likewise says the White House is hesitant to authorize transfers on stockpile grounds.

Any insider information on the inner workings of the Department of War is now complicated by the new media rules pushed by Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth. However, an anonymous source close to the issue put it more bluntly:

“There have been talks over blocking any potential Tomahawk shipments to Ukraine… In a sudden flashpoint stockpiles get depleted fast. The Red Sea showed us that much… China may escalate. Venezuela is another place to keep in mind.”

The Venezuela kicker isn’t random. The administration confirmed CIA operations in Venezuela and has escalated boat strikes in the Caribbean; Caracas has militarized parts of its border and declared new defense zones. Taken together, planners face a classic allocation problem: finite stocks, multiple theaters, rising risk, and supply uncertainty on the material inputs to rebuild what you shoot.

Meanwhile, the rare-earth fight with Beijing frames the whole debate. If magnet supply tightens or lead times stretch, replacing expended long-range munitions gets harder. That’s precisely why G7 ministers just pledged to coordinate on Chinese controls and fast-track alternative suppliers.

How to decouple from Chinese leverage in national security?

A. Treat magnets like munitions. Congress and DoD should place NdFeB/SmCo magnets on a managed, multi-year acquisition plan — with price floors and offtake to de-risk private investment (exactly the structure CSIS describes in its “mine-to-magnet” recommendations and mirrored in recent DoD–industry deals). Lock in demand for US/ally-made magnets across missiles, aircraft, ships, space, and EW. Track content at the part level; bar PRC content above de minimis thresholds in critical systems within 24–36 months.

B. Expand and modernize the stockpile — fast. GAO flagged gaps; fix them. Use supplemental funding to lift the NDS to a level aligned with a multi-theater contingency and to refresh aging inventories. Pair buys with transparent rotation/refresh rules, so materials don’t go stale. Build inventories of heavy REEs (Dy/Tb), NdPr, and processed magnet alloy, not just ores.

C. Build allied, not just domestic, capacity. Australia can expand feedstock and separation; Japan, South Korea, and the EU have magnet talent and capital equipment. Structure a “Magnet Quad”: US–Australia–Japan–EU (or Korea) with pooled finance, shared IP escrow, and reciprocal security-of-supply clauses — prioritizing defense orders during crises. Al Jazeera reporting shows Canberra is already positioning to backfill China-restricted supply.

D. Turn permitting time into a competitive advantage. Scissors’ point: we already have successes in rebuilding critical chains when we align money + demand + speed. Create a “National Security Minerals Corridor” with pre-cleared sites for separation and magnet plants, 24-month statutory decision clocks, and automatic interconnection priority for power-hungry facilities. Tie incentives to ESG performance so communities benefit and litigation risk falls.

E. Buy-side discipline. Mandate that all new Pentagon buys for systems with permanent magnets are PRC-free by default unless a national-security waiver is signed at the service-secretary level. Require whole-of-system BOM audits to catch “hidden” PRC content in sub-assemblies. Use the Defense Production Act to bridge cost gaps for compliant vendors in early years.

F. Field substitutions and thrift. You can’t redesign physics, but you can redesign usage. Fund near-term magnet reduction (topology optimization), remanufacture and recycling (REO recovery from scrapped motors, demilitarized kits, and e-waste), and high-temperature ferrite research for non-flight critical roles. DoD already seeded recycling pilots; now scale them.

G. Transparent meters, not vibes. Publish a quarterly dashboard: lead times for NdPr and Dy/Tb; license approvals/denials under China’s regime; US/ally nameplate capacity for separation and magnets; NDS drawdowns; and munitions burn-rate assumptions in current operations (classified where necessary, indexed publicly where possible). If industry sees the gap, capital will follow.

H. Scenario planning for split theaters. Wargame Ukraine + Western Pacific + Caribbean munitions demands against realistic replenishment curves under constrained magnet supply. If Tomahawks move to Ukraine, what replaces them, and how quickly, given the magnet bottleneck? The answer shouldn’t be a shrug.

China’s latest controls don’t guarantee a crisis — but they dramatically shorten the distance between a policy problem and operational risk. The US can still flip the script: treat magnets like munitions, fix the stockpile, buy allied, build domestic, and publish the scoreboard. The alternative is hoping the next shock waits for our supply chain to catch up.

The latest news in your social feeds

Subscribe to our social media platforms to stay tuned