EXCLUSIVE: Boots on the Ground in Venezuela? Military Capabilities and Potential Outcomes.

For months, tension between Washington and Caracas has been escalating in ways that feel eerily familiar. What began as an expanded “war on drugs” along the Caribbean Sea has grown into one of the most serious US–Latin America flashpoints since the Cold War. The Trump administration’s aggressive posture toward Venezuela — combined with a weakened Maduro regime, a volatile regional environment, and visible US military buildup — has created a situation where the line between deterrence and direct intervention is blurring fast.

This is an in-depth look at how the crisis got here, what military options are in play, how other global powers are responding, and what could realistically happen if this turns kinetic.

US–Venezuela relations have been deteriorating for years, but the current free fall began in late summer 2025. What’s unfolding now is less about drugs and more about regime change under the veneer of counter-narcotics.

Reports from The Guardian and our own previous coverage (‘US – Venezuela Falling Out. Are We Going to War?‘; ‘Crisis in the Caribbean. New Forever War on Drugs?‘) outline how the Trump administration has accused Nicolás Maduro’s government of facilitating cocaine shipments through Venezuelan ports and airstrips. Washington has designated Venezuela a “narco-state,” while Caracas insists these claims are political theater designed to justify intervention.

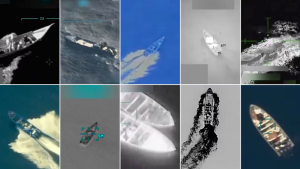

The conflict has expanded beyond rhetoric. Over the past few months, the US has conducted multiple drone and naval strikes on what it claims are “drug-smuggling vessels” across the Caribbean and eastern Pacific. According to PBS NewsHour and CNN, more than a dozen “narco-boats” have been hit — some in disputed waters near Venezuelan maritime borders.

Maduro responded by mobilizing coastal defense units and issuing fiery statements about “defending the homeland against imperial aggression.” Behind the bluster, his regime faces unprecedented domestic strain: hyperinflation, blackouts, and mass emigration. The opposition, led by María Corina Machado, has regained momentum, portraying Maduro as a liability whose alliances with Iran, Russia, and China have brought Venezuela to the brink.

Meanwhile, Washington has tightened sanctions, expanded surveillance cooperation with Colombia, and publicly floated the possibility of strikes on Venezuelan military installations allegedly tied to drug trafficking. According to Politico, Republican lawmakers like Rep. Dan Crenshaw have pushed for more aggressive measures, arguing that Maduro’s regime has become “a criminal enterprise masquerading as a government.”

In short, the two countries are now locked in a cycle of escalation, where each provocation risks crossing the threshold from rhetoric to war.

The buildup of American firepower near Venezuela is impossible to ignore. Satellite imagery obtained by Sky News and Reuters reveals US destroyers, surveillance aircraft, and carrier strike groups repositioning near Trinidad and Tobago, Guyana, and Puerto Rico — locations ideal for operations off Venezuela’s northern coast.

According to ABC News, President Trump has already authorized “limited contingency plans” for strikes on Venezuelan soil, though he insists “we’re not planning a war.” Pentagon sources told the network that the plans involve precision attacks on “dual-use” sites — airfields, radar arrays, and coastal depots believed to be facilitating drug shipments or harboring militant groups.

Leaked briefings from The Atlantic and New York Times describe covert CIA operations to map Venezuela’s military infrastructure and cultivate defectors inside the armed forces — echoes of early-2000s Iraq strategy but on a smaller, more flexible scale.

Venezuela’s military, for its part, is a shadow of its former self. A Le Monde analysis found that years of corruption, sanctions, and economic decay have left the army “hollowed out,” with an estimated single-digit number of functional fighter jets, Soviet-era Russian tanks, and a bloated command structure. The force is more suited to internal control and smuggling protection than external warfare.

According to Miami Herald reports, most of the Venezuelan Air Force’s Su-30 jets are grounded due to lack of spare parts, and naval vessels have been reduced to coastal patrols. Instead, the regime relies heavily on drones from Iran and shoulder-fired missiles from Russia. These could pose risks to US aircraft or ships — but they wouldn’t deter a sustained campaign.

In other words, while the US is positioning itself for precision power projection, Venezuela is bracing for symbolic resistance.

If Venezuela has little conventional military strength, it still has powerful friends.

Russia’s foreign ministry and state media have denounced Washington’s “imperialist aggression,” warning that US actions threaten “another Iraq on the Caribbean.” Defense News confirmed that a Russian Il-76 cargo plane landed in Caracas in late October carrying military advisers and electronic warfare equipment — more political theater than game changer, but enough to rattle nerves.

Colombian President Gustavo Petro speaks during a press conference at Casa de Narino in Bogota, Colombia, October 23 (Luisa Gonzalez / Reuters)

At the UN, Moscow and Beijing blocked a US-backed resolution condemning Maduro’s government. Cuba, Brazil, and Mexico have issued sharp statements against “foreign intervention,” while Colombia — long Washington’s top ally in the region — has been caught in the middle. President Gustavo Petro, now under US sanctions, has clashed with Washington over refueling rights for American aircraft and the handling of Colombian rebel groups near the border.

Meanwhile, Russia has hinted it could deploy Wagner mercenaries to bolster Venezuelan defenses — a move US officials dismiss as “bluff,” but that underscores how symbolic Moscow’s support could become tactical if fighting breaks out.

This patchwork of alliances makes Venezuela less isolated than Iraq or Libya were before intervention, yet not strong enough to deter US airpower.

Three major experts paint a sobering picture of what a US–Venezuela conflict would look like — and how it could spiral beyond its stated goals.

John Polga-Hecimovich, an Associate Professor of Political Science a the US Naval Academy, where he teaches courses on comparative politics and Latin American politics, argues the campaign would likely begin as “a regime-change operation wrapped in the guise of a counter-drug operation.” He predicts limited land or air strikes on “select military facilities, drug labs, and/or groups near the Colombian border,” intended to push Maduro’s generals toward defection or negotiation.

In terms of potential US tactics, Polga-Hecimovich points out Venezuelan realities:

“Venezuela is not actually a major drug producing country nor does it possess a clear strategic target like Iran’s nuclear facilities, meaning that the offensive would be more diffuse than what occurred in Iran.”

He, however, warns that Venezuela’s regime has proved remarkably resilient:

“The Maduro regime has proven to be quite resilient. It has survived country-wide protests several different times in the 2010s — culminating in the opposition’s gambit to name Juan Guaidó as interim president in 2019 — as well as external pressure in the form of economic sanctions and US and European visa limitations on senior political and military members. Throughout this, Maduro has retained the loyalty of his Defense Minister, Vladimir Padrino López, and other key allies. In this sense, the regime has proven to be more enduring than critics have hoped.”

Polga-Hecimovich believes a full-scale deployment of US troops remains unlikely — but cautions that “given how this confrontation has escalated,” he “wouldn’t discard any possible course of action right now.”

More on Venezuelan domestic politics can be found in Polga-Hecimovich’s most recent co-edited book, ‘Authoritarian Consolidation in Times of Crisis. Venezuela under Nicolás Maduro.’

Douglas Farah, president of IBI Consultants, a national security consulting group specializing in security threats in Latin America, sees the risk of escalation as “very high” but doubts there will be a full-scale US invasion.

“Venezuela is too big to occupy or invade,” he told Wyoming Star.

He describes Venezuela’s army as top-heavy and poorly maintained:

“Venezuela has little formal military capacity… There are more than 2,000 generals for a military of 140,000. The US has fewer than 500 for a military of 1.3 million. The Venezuelan military is designed to control key economic resources (ports, airports, and oil extraction), not fight an external enemy. There have been few new armaments, outside of Iranian drones and Russian Igla missiles, over the past 10 years… The air force has at most 6 aging Russian fighter jets.”

In his assessment the real threat lies in irregular actors: armed militias, FARC dissidents, and ELN guerrillas with decades of combat experience.

“The FARC dissident groups and the ELN, both originally from Colombia, each have almost 50 years of combat experience in Colombia’s civil wars and in Venezuela over the past 10 years. So they can wage guerrilla warfare that would make occupying the country or exercising significant control, either for US troops or a new government, extremely difficult,” Farah warned.

He predicts regional instability would follow:

“Guyana to the east is most vulnerable and allied with the US. Colombia to the west is much friendlier to Maduro and will likely receive a new, large influx of refugees. If there is deep instability in Venezuela, it will spread across the region as local, regional, and extra-regional criminal organizations adapt, find new seams in the system, and operate more freely.”

Farah explores the Latin American criminal organizations in this FIU piece.

He also sees little possibility for serious international reaction:

“No one will be willing to invest deeply in defending the Maduro regime militarily. Russia is overwhelmed in Ukraine, China wants stability, and Cuba is already running the Maduro intelligence structures but has nothing else to offer. China and Russia will be very active in multilateral forums like the UN, CELAC, and others, vetoing any motions against Maduro and offering rhetorical support. Cuba and Brazil will do the same for Latin America (OAS, ALBA, etc.), but that will be the most they can do. I doubt they will try to do more in what they know would be a losing cause.”

Brian Fonseca, director of Florida International University’s Institute for Public Policy, has a similar view of an international response.

“I don’t think Colombia, Cuba, or Brazil would intervene directly. At this stage, countries like Cuba are terrified that they’re next on Secretary Rubio’s targeting list. So they’re probably going to keep their head down, and that’s been the case for a while… Other than sending doctors around, they’re pretty isolated. With Brazil and Colombia, it’s going to be purely rhetorical geopolitical posturing — condemnations and denunciations — with Petro and Lula being sort of opposed to Trump… China plays it really carefully… They’re already locked into negotiations with the United States over trade conflict. They’re not going to get involved.”

However, he warns that Russia could play spoiler:

“They’d love to see the Americans engulfed in conflict in Venezuela. This might take attention away from places like Ukraine or Eastern Europe… They might ‘light a match and walk away’ through things like sabotage if the Americans start to get a little close. Otherwise they’ll provide some type of material support or technical support, but nothing overwhelming. Maybe the Wagner Group might jump in.”

Overall, he believes the most likely US scenario is offshore strikes designed to fracture the regime from within.

“I think that the United States is going to strike targets inside Venezuela within the next few days,” he says.

Fonseca’s best case scenario: elite fractures that allow a transitional government to take power with US and regional support, restoring democratic institutions and rebuilding the economy. The worst case: an Iraq-style quagmire that inflames regional crime, migration, and anti-American sentiment.

Fonseca is skeptical of a boots-on-the-ground approach.

“The capability that’s been moved into the Caribbean is to give the US the ability to strike targets from offside, off the coast, so that we don’t have to run the risk of an escalation by flying F-35s to do strategic strikes inside Venezuelan territory. Being able to strike those targets from off the coast gives the United States a little bit of space so that it doesn’t run the risk of the Venezuelans shooting down a US aircraft.”

On the question of Venezuelan military capabilities, Fonseca echoes Farah:

“From a force structure, the Venezuelan military has set up surface-to-air missiles across the country. They do have a significant amount of troops and some material assets they got largely from the Russians and some outdated US stuff, but it’s been poorly maintained, and the training has been rough. I don’t think that they can fight a world-class military at the stage they’re at now… The biggest concern might be the militia only in the context of a land invasion or conflict on the ground, where these militias are embedded in communities all across the country. In fact, I’ve seen estimates where ‘the colectivos’ controlled up to 10% of the cities.”

So what happens next? Several outcomes are on the table:

1. Surgical strikes and elite defection. The most likely near-term path is a limited air or missile campaign targeting key military or logistical sites. If successful, it could trigger defections among Maduro’s inner circle and open a window for negotiated transition — what US strategists quietly call the “soft landing.”

2. Regime resilience and prolonged sanctions. If Maduro weathers the blows, sanctions will deepen, and the US might be forced into a long containment strategy. This risks humanitarian disaster, regional migration surges, and a potential rally-around-the-flag effect in Venezuela.

3. Accidental escalation. One drone or missile misfire could shift everything. If US strikes kill senior Venezuelan officers or civilians, Maduro could retaliate with drones or surface-to-air fire, forcing Washington to escalate in kind.

4. Regional blowback. Colombia’s fragile truce with guerrillas, Guyana’s border vulnerabilities, and Caribbean states’ economic dependence make the region susceptible to spillover — fuel smuggling, refugee flows, and organized crime spikes.

Whether the US actually puts boots on the ground may depend less on Caracas and more on politics in Washington. Trump has promised “no new wars,” yet he’s also built his foreign policy on visible strength and deterrence. In that sense, Venezuela offers him both an enemy and an opportunity — to showcase American might without a long-term occupation.

But the history of US interventions in Latin America is a warning: what starts as a “limited operation” often morphs into something costlier and longer than planned. As The Conversation noted:

“Washington’s squeeze on Venezuela won’t bring about a rapid collapse of Maduro. It might boomerang — fueling anti-American sentiment and further destabilizing the region.”

For now, both sides are playing a high-stakes waiting game in the Caribbean. The ships are already there, the targets mapped, and the rhetoric sharpened. Whether that turns into missiles flying — or a last-minute off-ramp — may define not just the next chapter of US–Venezuela relations, but America’s broader role in Latin America for years to come.

The latest news in your social feeds

Subscribe to our social media platforms to stay tuned