The US government shutdown that began on October 1 has been a stress test for America’s safety net. No program has felt the strain more viscerally than SNAP, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. Here’s what happened, why it matters, and what comes next.

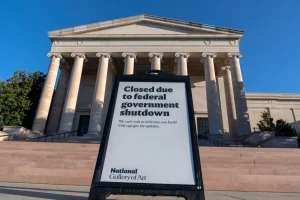

At midnight on October 1, 2025, federal funding lapsed. Agencies dusted off contingency plans, “essential” workers kept showing up without pay, and millions of Americans encountered the government as a locked door. The White House’s running “shutdown clock” framed the stalemate in real time: days, hours, and minutes of paralysis cascading into concrete disruptions.

Member offices scrambled to triage impacts — what’s open, what’s closed, who still gets paid, and who doesn’t. Rep. Greg Stanton’s constituent FAQ is emblematic: Social Security checks continue; tours are canceled; new student aid may soon strain; SNAP could pause in a prolonged impasse. By late October, his office posted that the administration planned to pause SNAP contributions starting November 1, a sign of what was coming.

If you needed the civics refresher: Congress writes twelve annual spending bills. When they’re late, a continuing resolution (CR) keeps money flowing. Without a CR — or full appropriations — the government partially shuts down.

Forty days in, a bipartisan procedural vote in the Senate on November 9–10 finally cracked the stalemate — an initial step toward reopening, with funding likely extended into late January while separate fights (like ACA tax credits) moved to later votes. Outlets reported the same arc: a cross-aisle coalition advanced a compromise to reopen much of the government while deferring the thorniest healthcare subsidy dispute.

House member sites like Rep. Ed Case’s aggregated “what closes, what stays open” answers for everyday life, but the headline for low-income households was unmistakable: food benefits were at risk as November began.

Shutdowns don’t fall evenly. The Bipartisan Policy Center estimates at least 670,000 federal employees furloughed and 730,000 working without pay early on — with millions of paychecks missed if the shutdown persisted into November and December — effects that rippled into local economies and household budgets.

For states, the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL) laid out the knock-on effects across programs, from unemployment services to nutrition aid. In plain terms: even if a benefit is legally “mandatory,” the staff and systems that make it real can be constrained or idled, and the timing of monthly payments can become the difference between groceries and bare shelves.

All of that collided with the most sensitive line item in many family budgets: SNAP, commonly called “food stamps.” A late-October explainer wave across national outlets warned recipients to brace for uncertainty in November disbursements — with advocates and analysts flagging the cascading risks when benefits arrive late or not at all.

At its core, SNAP is a federal entitlement administered by states that helps low-income households afford food via an EBT card. Eligibility generally keys off income (around 130% of the poverty line for gross income), household expenses, and work rules for certain adults. USAGov offers the plain-English how-to: who qualifies, how to apply, and how to check a balance. Johns Hopkins summarizes the public-health case: SNAP reduces food insecurity and improves dietary quality in ways other programs can’t replicate. Feeding America underscores the scale: SNAP delivers far more meals than food banks can, even in emergencies.

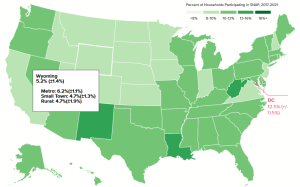

Look closer and the importance becomes local, not abstract. FRAC’s interactive maps show SNAP’s footprint by congressional district, state, and community, and spotlight older adults — a population for whom even small disruptions have outsized health consequences. These tools quantify what advocates see daily: every county has households that depend on SNAP to keep pantries stocked.

To see how the system functions on the ground, open a state page. Wyoming’s Department of Family Services outlines application steps, notices, and contact points; the USDA state directory provides the federal counterpart. It’s a reminder: SNAP is federal money but state-run, and when D.C. freezes, states are left choosing between advancing their own dollars or asking families to wait.

Kim Moscaritolo, Hunger Free America’s State Policy Director, gave a statement to Wyoming Star:

“Roughly 42 million people nationwide — including children, seniors, veterans, and people with disabilities — rely on SNAP, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. SNAP provides eligible families with money to purchase food and beverages. Generally speaking, a household’s income must be at or below 130% of the poverty line to be eligible for these benefits. In 2023, about 39% of SNAP participants were children, 20% were elderly, and 10% were nonelderly individuals with a disability. According to USDA food insecurity data, 78,806 Wyoming residents (13.7%) were found to live in food insecure households between 2021 and 2023. This includes 19.5% of children in the state, 11% of employed adults, and 8.3% of older Wyoming residents. In communities across the country, individuals and families spend countless hours going to food pantries and soup kitchens to stay fed, which impedes their ability to work a steady job and take care of their children. In addition to freeing up time to put towards gainful employment and taking care of loved ones, SNAP also reduces poverty and grows the economy. Each year, SNAP lifts millions of Americans out of poverty, and every dollar of new benefits generates $1.80 of economic activity, often in communities that need it most. The cuts that have been signed into law by Donald Trump could result in up to 4 million people losing some or all of their SNAP food benefits once the changes are fully implemented, according to the Congressional Budget Office. While no other federal program can compare to SNAP, the WIC program, for Women, Infants, and Children under 5, can help parents and children access healthy food for themselves and their families.”

FRAC’s and JHU’s framing matches that lived reality. And in states like Wyoming, where USDA data show elevated food-insecurity pockets, SNAP’s stabilizing role is disproportionately important.

The story of November SNAP payments is, bluntly, chaos by memo. The USDA’s November 2025 update acknowledged limited funding during the shutdown and directed states on administrative expenses and the possibility of partial payments, while litigation ping-ponged between full and partial benefit obligations.

By November 7, a Supreme Court justice temporarily stayed a lower-court order that had compelled full November benefits. That pause unleashed a rapid sequence: USDA told states to “undo” full payments and revert to partials (widely cited as about 65%), warning of potential clawbacks and administrative funding risks for noncompliance. AP and other outlets documented the reversals and the confusion across state agencies.

On the ground, the human translation was immediate. Wyoming Public Media reported on the Supreme Court stay even as some states had started to send full benefits. WyoFile chronicled social workers “scrambling” to handle surging need — food lines, emergency pantry referrals, clients missing prescriptions because grocery money was gone. Cowboy State Daily captured both the state emergency declaration (up to $10 million to shore up food aid and a temporary “junk food” waiver to increase flexibility) and community anxiety about what comes next.

Nationally, NCSL summarized the policy shifts coming out of the “One Big Beautiful Bill” (the summer domestic policy package), including expanded work requirements, noncitizen eligibility changes, and higher state cost shares for administration in later years — changes that would have been complex in the best of times, now arriving amid a shutdown and payment timing crisis.

Advocacy groups argued that Washington was leaving money on the table. Analysts pointed to contingency reserves that could legally be used for regular SNAP benefits, contending that the Administration’s reading was too restrictive and would force deep cuts until Congress reopened the government.

Add in-state communications like Wyoming DFS’s October warning that shutdown-related issues might halt SNAP payments — and the picture is clear: front-line agencies were forced to message uncertainty to households that budget to the day.

Dr. Angela Rachidi, a senior fellow and the Rowe Scholar in opportunity and mobility studies at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), an expert in poverty and the effects of federal safety-net programs on low-income individuals and families in America, said:

“Currently, the federal government is planning to partly fund SNAP benefits in November using available funds. But until the federal government reopens, they do not have enough appropriated funds to send full benefits. And to be clear, SNAP was not cut — Congress has not funded the program, but they will eventually. When the government reopens, SNAP households should receive their full benefits (including any retroactive payments). Nonetheless, households will experience a disruption in benefits this month… SNAP helps nearly 12% of the US population… One-third of SNAP households involve children. 60% of SNAP households involve a single-person, many of them elderly… The US federal government provides other safety net programs, which will help fill in some of the gaps… Schoolchildren will still receive federally-funded school meals… Emergency food programs will continue to operate through food pantries and soup kitchens. States can also fund SNAP benefits until the federal government reopens, but there is no guarantee that the federal government will reimburse them. I would expect this disruption in SNAP benefits to result in more families utilizing other programs to fill the gaps, as well as to fall behind on other expenses, such as rent and utilities.”

By the second week of November, the legal and political battlefield narrowed to a practical question: What can recipients expect this month — and next?

A district judge ordered full November SNAP; a Supreme Court stay paused that ruling; the Administration then instructed states to reverse full payments where they’d already gone out or not to issue them, pending further litigation. AP and The Independent captured the sequence and the state backlash.

The states’ response has been mixed. Some moved to shore up aid with state dollars; others followed USDA’s partial-payment guidance to limit clawback risk. Senate action suggested a path to reopen government and, with it, restore full SNAP funding under normal order.

Dr. Sara N. Bleich, the inaugural Vice Provost for Special Projects at Harvard University, Professor of Public Health Policy at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, and a faculty member at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government, commented:

“If the shutdown extends through November… SNAP contingency funds, which total about $4.5 billion, will be exhausted if they are fully utilized for this month. However, the Administration does have the authority to transfer funds across accounts within a single agency. For example, resources in the Child Nutrition account — approximately $30 billion, which funds school meals and related programs — could be tapped for December without disrupting regular operations. For families, any delay in benefits or provision of only partial benefits creates enormous strain, forcing many to make difficult choices between paying rent, buying food, or meeting other essential needs. Food banks and states are stepping up to help, but they cannot come close to filling the gap left by the federal government — SNAP provides nine meals for every one that food banks can supply. The shutdown’s ripple effects will also hurt local economies, as grocery stores may lose significant revenue, potentially resulting in layoffs. Most concerning, deepening food insecurity is linked to chronic health problems like diabetes and high blood pressure, compounding the harm to families.”

If Congress finalizes a deal and the President signs it, SNAP should resume normal funding, and households can receive retroactive amounts for any shortfall in November. Until then, states are navigating legal minefields, recipients are juggling partial deposits, and grocers are managing unpredictable EBT volumes — classic second- and third-order effects of a shutdown.

SNAP is not a niche welfare line item. It’s the backbone of US anti-hunger policy — bigger than food banks, reaching tens of millions monthly, and deeply embedded in local economies. When a shutdown turns SNAP into a political ping-pong ball, it’s not just the federal ledger at risk; it’s the metabolism of whole communities.

Policymakers will argue about contingency reserves, cross-account transfers, and statutory flexibilities — and they should. But the operational lesson is simpler: the closer a federal program is to a family’s next meal, the less tolerable delay becomes. SNAP’s design — federal funding, state administration — keeps it nimble in normal times, but in shutdown conditions it becomes a game of who blinks first: Congress, the Administration, or states staring down empty fridges and angry checkout lines.

Until the ink dries on a reopening bill, that’s where SNAP sits — too big to fail cleanly, too essential to leave in limbo.

The latest news in your social feeds

Subscribe to our social media platforms to stay tuned