The original story by Camila Domonoske for NPR.

The US economy runs on big rigs. Truckers haul nearly everything we buy — food, fuel, furniture, your latest online impulse purchase. But the job itself is grueling: long hours, lonely stretches of highway, and a constant mix of stress and boredom.

“I say it’s the last honest job,” says Aaron Isaacs, a California truck driver. “Because you come out here and you earn your money.”

Now technology is moving into trucking in a big way. On one side, you’ve got new driver-assistance tools promising to make highway life safer and less exhausting. On the other, companies are testing fully driverless trucks that don’t need a human in the cab at all.

So the question hanging over the industry is simple — and uncomfortable:

Will tech make truckers’ lives easier, or push them out of the driver’s seat altogether?

This fall, Volvo Trucks invited reporters to a closed test track in South Carolina to try out its redesigned Volvo VNL, a long-haul semi. As a car reporter used to sedans and pickups, climbing way up into an 18-wheeler was a little intimidating.

The air-suspension seat bounced, the cab swayed as 72,000 pounds of cargo started to roll — but once underway, the truck was surprisingly easy to handle.

Thanks to a ring of cameras, blind spots basically disappeared. Adaptive cruise control automatically handled speed and distance. In a demo, when a car cut in front and slowed down, the truck calmly eased off the throttle and matched its pace. In simulated stop-and-go traffic, it crept along without needing constant taps on the brake or accelerator.

“I would say that this truck’s easier to drive than most cars nowadays,” said Joel Morrow, president of Alpha Drivers Transportation and proud owner of a bright purple VNL.

For him, features like these don’t just look cool — they reduce stress.

Car buyers have had driver-assist tech for years: lane keeping, adaptive cruise, automatic braking. But in heavy trucks — where vehicles are business assets, not vanity purchases — new gadgets tend to roll out more slowly. Early systems also annoyed truckers with constant beeping and false alarms, turning “safety features” into just another headache.

Volvo and other manufacturers say they’ve been working to fix that, making systems that actually help drivers instead of nagging them.

They have a strong business reason. Long-haul driver turnover is notoriously high — averaging over 90% annually at big fleets for more than two decades, according to data analyzed for Congress.

The American Trucking Associations (which represents carriers) says the problem is a shortage of drivers. Truckers themselves often point to low pay, chaotic schedules, lack of parking, and basic indignities — like being denied bathroom access — as reasons they quit or bounce between jobs.

Technology can’t solve all of that. Cameras and software won’t create more truck stops or improve dispatch practices. And driver groups warn that no amount of gadgetry can replace proper training and experience.

But Magnus Koeck, Volvo Trucks’ vice president of strategy and marketing, thinks better design still matters. If the cab is safer, more comfortable and easier to operate, he says, drivers are more likely to stick around — which saves companies real money.

Replacing a single driver, he estimates, can cost at least $10,000 in recruiting, training, and downtime. So investing in better seats, clearer displays, smarter sensors and a decent bed isn’t just being nice; it’s protecting the bottom line.

To show off the comfort factor, Volvo even had journalists spend a night in the truck. Inside, the sleeper cab felt a lot like a compact RV:

- a table and chairs that convert into a fold-down bed;

- a small fridge, microwave and TV;

- clever little storage cubbies.

It was cozy. But it raises a big question: if the future is truly autonomous, will trucks even need beds — or drivers — at all?

A week later, in a lot near a Volvo Group office, there was another Volvo VNL on display. From the outside, it looked similar. Inside, it was stripped-down: no microwave, no TV, no mattress — just open space behind the seats.

This truck was designed to drive itself.

Volvo Autonomous Solutions is one of several companies working with Aurora Innovation, a self-driving tech firm building a system that uses cameras, radar, lidar and powerful onboard computers to control big rigs without human input.

Other startups like Waabi and Kodiak are in the same race. Texas, with its long highway stretches and permissive rules, has become a major testing ground.

In Dallas, at Aurora’s terminal, the tech isn’t obvious at first. The yard looks like any other logistics lot — until you notice the odd little sensor “horns” on top of the trucks.

Inside one of Aurora’s Peterbilt semis, veteran truck driver A.J. Jenkins sat in the front seat. But he wasn’t there to drive — his official role was “observer.”

The truck beeped, rolled out of the lot, paused at a stop sign, crossed an overpass and merged onto the highway toward Houston. It settled just under the speed limit in mid-morning traffic.

Jenkins kept his hands in his lap, or behind his head, as the truck handled everything itself: lane changes, merging, adjusting to other cars. There were no dashboard graphics showing what the system “saw” or planned to do — because the end goal is to have no one in the cab at all.

At one point, the truck slowed slightly to let a merging car slip in ahead.

“We try to be the most courteous truck on the road,” Jenkins said.

Before he monitored self-driving rigs, Jenkins taught people to get commercial licenses. In a way, he says, he also helped teach this software to drive. In Aurora’s early days, he drove routes while the system recorded what he did and what the sensors saw. Engineers used those logs to refine the “Aurora Driver” system.

Later, he would ride while the truck drove, ready to grab the wheel in case of mistakes. He remembers when the software update finally fixed the truck’s early habit of weaving inside the lane.

“We stayed right in the middle of the lane,” he said. “It was awesome.”

Then he upgraded the compliment:

“It was boring.”

That was four years ago. Today, Aurora says it has driven more than 100,000 autonomous miles on real freeways with freight — flooring, beverages, packages — and no human interventions, all without a serious safety incident. The company plans to start running fully driverless cargo loads in spring 2026.

Most Americans aren’t exactly relaxed about driverless vehicles. Surveys by AAA and others regularly find that a majority of people feel uneasy or outright afraid of them.

Truckers share that anxiety — and then some.

“Computers don’t work all the time,” says Isaacs, the California driver and Teamsters member. “There is no technology that is 100% proven to work all of the time, every single day.”

He also argues that human drivers are better at reading subtle cues — spotting the guy scrolling on his phone, the car drifting in its lane — and adjusting early.

“That’s a big part of the job, is anticipating the actions of others,” he says. “And I don’t believe that a computer can do that.”

Autonomy advocates think that’s exactly what computers can eventually do better. They point out that human error causes the vast majority of crashes. Computers don’t text, don’t fall asleep, don’t zone out after 9 hours on I-40. And with 360-degree cameras and radar, they can monitor more than a pair of human eyes ever could.

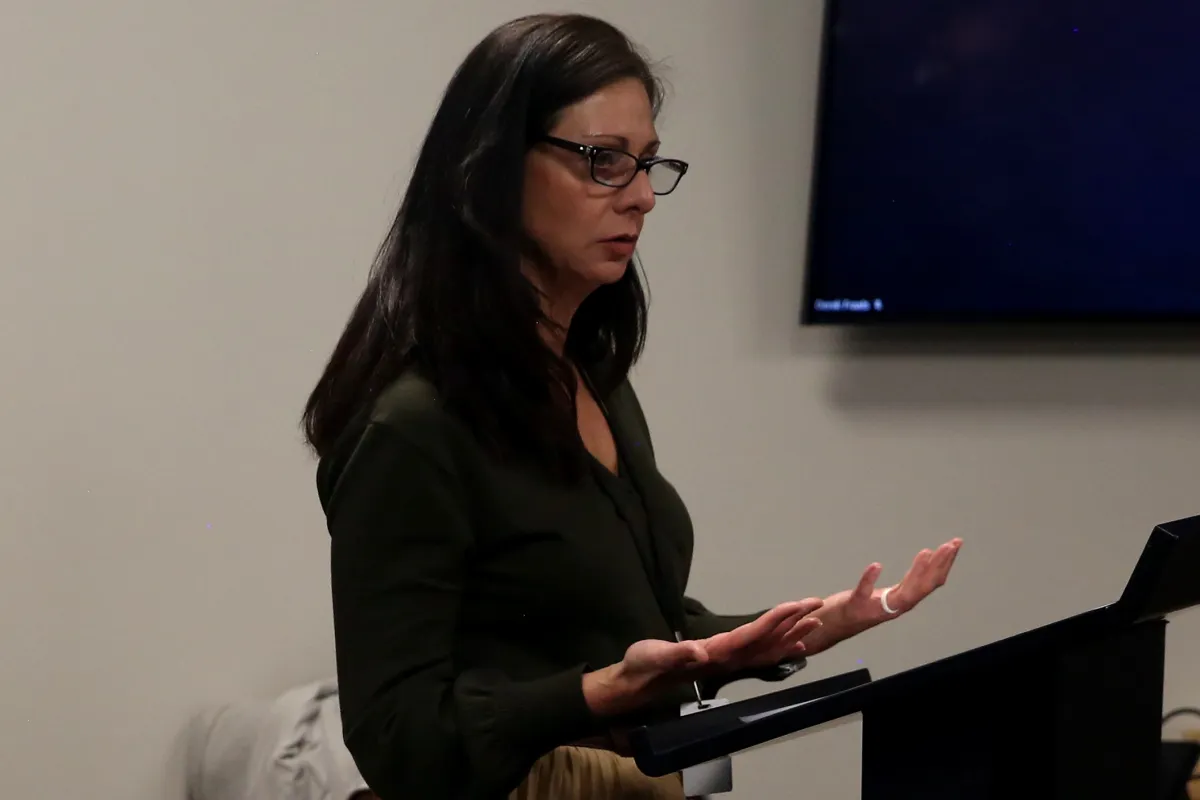

Aurora president Ossa Fisher says their tech has “superhuman capabilities, responding to the world much faster and [more] consistently than a human ever could.”

She also says the company has spent years testing failure scenarios — both digitally and on real roads — to ensure there are multiple backups and safe shutdown modes if something goes wrong.

Critics aren’t convinced. Todd Spencer, president of the Owner-Operator Independent Drivers Association, says drivers are basically being asked to take tech companies at their word that everything is safe. His group is also worried about security — not just bugs, but outright hacking.

He imagines a nightmare scenario: someone seizes control of a truck and uses it as a weapon, something terrorists have already done with ordinary, human-driven vehicles.

Fisher counters that Aurora has built its system to make remote control impossible.

“We have a zero-trust security system where you cannot operate the truck remotely even if you wanted to,” she says.

The truck’s onboard brain makes all the decisions, and even Aurora employees can’t steer it from afar.

For truckers, there’s one fear that connects all the rest: their livelihoods.

“When you start taking drivers out of trucks, you’re taking food off of people’s tables,” Isaacs says. “You’re taking the braces out of that kid’s mouth.”

Fisher argues that’s not what Aurora is doing — at least not now. She points back to that sky-high turnover rate the ATA cites and suggests that autonomy will fill a labor gap, not wipe out good jobs.

“If you are a truck driver today, your services will be in demand until the day you choose to retire,” she says.

She also stresses that Aurora is focused on very long-haul routes — multi-hour, mostly straight highway stretches that are boring for humans but ideal for a system that doesn’t need sleep. Short-haul and local work, she says, are not on their near-term roadmap.

“So we’re taking the most difficult, the least desirable — depending on how you look at it — jobs and filling that role with very safe, autonomous technology,” Fisher says.

But what counts as “least desirable” depends on whose paycheck you’re looking at. Some drivers want to stay close to home. Others earn their best money on long runs.

Mike Bradshaw, a Teamsters member in Texas who hauls car carriers, says he likes going thousands of miles at a time. With union pay and enforced rest breaks, long-distance runs are where he does best.

“It’s profitable for me to take those longer runs,” he says. “That’s what I look for.”

In the long run, Fisher believes automation will touch almost everything on the road.

“I think we’ll automate most things,” she says.

She won’t guess how many years it will take, but she’s confident that one day we’ll be grateful that trucks drive themselves.

She also insists that autonomy will create new jobs: people to remotely monitor fleets, technicians and mechanics to test and maintain vehicles, and support roles around terminals and logistics hubs.

The Teamsters aren’t pretending nothing’s changing.

“Technology is coming,” says Brent Taylor, the union’s southern region vice president. “It’s coming fast.”

The union has already negotiated some contracts that require a human in the cab whenever an autonomous truck is on the road. It’s also pushed — with less success — for laws mandating human operators.

And if the job itself changes from driver to something else, Taylor says the union’s goal is to make sure those new roles are still good, middle-class jobs.

“I don’t think we’re sitting around with our head in the sand thinking that it’s never going to happen,” he says. “Whether it’s five years, 50 years, 100 years, I mean, it’s coming.”

For now, trucking is in a strange in-between moment. On one lane, companies are racing to build trucks that pamper and protect drivers. On the next lane over, they’re perfecting trucks that don’t need drivers at all.

Which lane becomes the main highway — and how many people still earn their living behind the wheel — is a decision playing out right now on test tracks, highways and bargaining tables across the country.

The latest news in your social feeds

Subscribe to our social media platforms to stay tuned