Gordon Scales Back Pronghorn Corridor Plan, Overrules Wildlife Commission and Sparks Backlash

The original story by for WyoFile.

Wyoming’s long-awaited effort to officially protect its first pronghorn migration corridor just hit another political twist — and this time, Gov. Mark Gordon is the one reshaping the map.

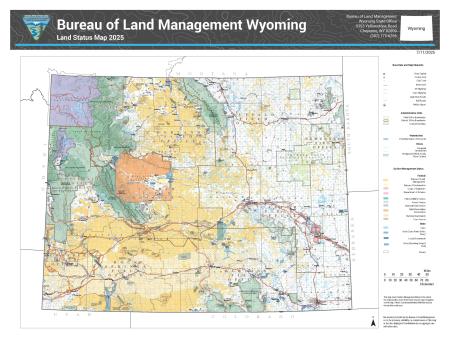

On Thursday, Gordon announced he’s advancing the Sublette Pronghorn Migration Corridor designation, a process that’s been dragging on for six years. But there’s a catch: he’s removing two major eastern segments — the Red Desert and the area east of Farson, known as the Golden Triangle — from the plan.

That decision immediately rolled back a unanimous vote from his own Wyoming Game and Fish Commission, which last month restored those same segments after widespread criticism that the state was bending to livestock industry pressure.

Under Wyoming’s migration policy, the governor has final say, and this marks the first real test of that system. It’s also a clear look at how tricky — and political — protecting wildlife can be in landscapes packed with oil, gas, grazing, and federal land battles.

Gordon did not make himself available for an interview.

The two trimmed segments cover more than 270,000 acres of crucial pronghorn habitat used by roughly 5,000 migrating animals. It’s one of the longest pronghorn migrations in North America — better known as the “Path of the Pronghorn.”

But those two segments have long been a sticking point. Ranchers argue they’re lower risk and shouldn’t be included. Conservationists say that’s nonsense — the habitat is vital, and removing protections opens the door for more development.

This fall, the Wyoming Stock Growers Association pushed hard to cut them out. Its longtime VP, Jim Magagna — whose ranch sits right next to the disputed area — praised the governor’s move.

“I think they did it because the science justified taking that approach,” Magagna said.

Wildlife advocates strongly disagree, pointing out the science didn’t suddenly change — but industry interests did.

The Bureau of Land Management currently has an Area of Critical Environmental Concern (ACEC) protecting much of the contested area east of Farson. But that plan is under fast-track revision, and oil and gas companies have shown strong interest in leasing the Golden Triangle, which experts describe as some of the most ecologically valuable sagebrush habitat in the state.

In other words: protections might shrink just as development heats up.

Some groups thanked Gordon for at least advancing something after years of delays. But most were deeply disappointed.

Craig Benjamin of the Wyoming Wildlife Federation struck a cautious middle ground:

“With pronghorn populations down roughly 40%, it’s important we protect as much of the corridor as feasible.”

The Wyoming Outdoor Council wasn’t nearly as diplomatic. Meghan Riley didn’t hold back:

“This decision subverts the will of the people and the direction of the Commission. Thousands of pronghorn will now be excluded from protection.”

Retired Game and Fish biologist Rich Guenzel called it what many wildlife folks are saying quietly:

“A political decision — not a biological one.”

The state will form a local working group made up of:

- 2 agriculture reps;

- 2 industrial/energy reps;

- 2 conservation/hunting reps;

- 1 motorized recreation rep.

Applications are open through Dec. 31.

That group will review habitat risks, local economic impacts, possible highway projects and other factors, then send recommendations back to Gordon.

He can then designate the corridor (first since 2019), send it back for changes, or kill the designation entirely.

It’s a high-stakes decision — not just for pronghorn, but for how Wyoming balances wildlife with energy and livestock interests moving forward.

Federal agencies have tried to protect parts of this migration for decades. In 2008, the Bridger-Teton National Forest protected its section and popularized the “Path of the Pronghorn” name. But much of the southern migration route — mostly BLM land — remains unprotected due to political pressure.

Now, after yet another turn in the road, Wyoming’s first official migration corridor may move ahead — but only partially, and not without controversy.

Whether the remaining eight segments will be enough to keep the iconic pronghorn migration intact is a question the next few years — and the next few political decisions — will answer.

The latest news in your social feeds

Subscribe to our social media platforms to stay tuned