EXCLUSIVE: When Power Kidnaps the Law: The Abduction of Nicolás Maduro and the Death of International Order

On 3 January 2026, American special forces swept through Caracas, seized Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro and his wife Cilia Flores and whisked them aboard a US vessel. Hours later President Donald Trump appeared at Mar‑a‑Lago to announce that Washington would “run the country” and ensure Venezuela’s oil riches were “used properly.”

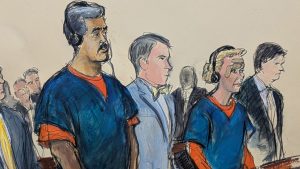

Maduro and Flores, bandaged, bruised and flanked by US marshals, made their first appearance in a New York courtroom this week. Through an interpreter, Maduro told Judge Alvin Hellerstein:

“I was captured at my home in Caracas, Venezuela … I am still president of my country … I am a decent man.”

Both he and Flores pleaded not guilty to narcotics and weapons charges and signalled their intention to challenge their detention. Their lawyers said the pair were kidnapped, demanded consular access and promised motions attacking the indictment and the manner of their seizure.

Trump, for his part, declared:

“We’re in charge,” and warned interim Venezuelan leader Delcy Rodríguez that she would pay a “very big price” if she defied him.

The images of a foreign head of state shackled and transported across international borders jarred many observers, but the lawfulness of the operation has been hotly contested. The administration has claimed it merely executed a law‑enforcement action against a drug lord. Critics argue that, far from upholding the rule of law, the United States has torn the post‑1945 legal order asunder.

To understand what this moment, in which power appears to be overtaking law, could mean for the future of the global order, The Wyoming Star reviewed the relevant legal framework and spoke with leading international law scholars and foreign policy experts.

What the law says

Article 2(4) of the United Nations Charter declares:

All Members shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state.

Under Article 51, force is justified only when a state is exercising its inherent right of self‑defence against an armed attack and must be reported to the Security Council. The Organization of American States (OAS) goes even further.

Articles 19 and 21 of the OAS Charter prohibit any state from intervening in the internal or external affairs of another, bar “armed force … or any other form of interference”, and affirm that a state’s territory is inviolable: it may not be the object of military occupation or “other measures of force” by another state.

International law also accords absolute immunity to sitting heads of state, heads of government and foreign ministers. As the International Court of Justice explained in the Arrest Warrant case, immunities are not personal favours but essential to ensure officials perform their duties on behalf of their states.

The Court concluded there is no exception to these immunities, even for those suspected of grave crimes. Scholars summarise the rule succinctly:

“Under customary international law, ‘head‑of‑state’ immunity provides absolute immunity to sitting heads of state, heads of government, and foreign ministers.”

“International vandalism”: Alfred‑Maurice de Zayas’s verdict

Alfred‑Maurice de Zayas, a Cuban‑American jurist and former UN Independent Expert on international order, is unsparing.

“The kidnapping of a head of state is an international crime,” he said, adding that it violates Article 2(4) of the UN Charter, the sovereignty principle in Articles 1 and 2, the OAS Charter’s non‑intervention clauses, and the head‑of‑state immunities of customary law.

“It entails civilizational retrogression. It is yet another example of the contempt that Trump has for international law, the UN Charter and civilisation itself. Trump sees himself as a Roman emperor – legibus solutus – above all law.”

De Zayas has stressed that Trump is following a trail blazed by previous US presidents.

“His predecessors got away with major violations of international law … Ronald Reagan bombarded Grenada, George HW Bush bombarded Panama and tried Manuel Noriega, Bill Clinton bombarded Yugoslavia and destroyed the Chinese embassy, George W. Bush and the ‘coalition of the willing’ bombarded Iraq and killed an estimated one million people – in total impunity. Back in 2020 Trump kidnapped the Venezuelan diplomat Alex Saab and had him tried by a court without jurisdiction.”

This culture of impunity, he argues, has been tolerated by America’s allies, creating the conditions for today’s abuses. Asked what precedent such an abduction sets, de Zayas returned to the role of the international community.

“The UN is blocked through the US veto – which has protected even the genocide being committed by Israel on the Palestinians. Thus, forget the UN. States must act on their own …

They should take concrete measures to ‘sanction’ the US by stopping all purchases of weapons from the US, F‑16, F‑35, Boeing, Lockheed‑Martin, Raytheon, stop buying US automobiles and other export items. Regional organisations like BRICS could and should coordinate the international ‘pushback’.”

For de Zayas, this episode is not about Trump alone.

“Donald Trump is not setting any new precedent – Bill Clinton did as much damage to international order as George W. Bush and even our ‘saint’ Barack Obama, who orchestrated the coup against [Ukraine’s former] President Victor Yanukovich …

It is up to us to reaffirm the values of the UN Charter and the commitment to peace through negotiation.”

The US, he contends, is violating not only international law but its own Constitution; yet politicians offer only lip‑service to the rule of law.

“Nothing new under the sun”: Samuel Moyn on the absence of precedent

Samuel Moyn, a legal historian at Yale Law School, agrees that Trump’s operation is unlawful, but cautions against overstating its novelty.

“Every act is different and new, but what is not new in the world of great powers [is] that [they] treat rules as discretionary,” he notes.

Trump is not setting a precedent so much as illustrating a longstanding problem. The episode, Moyn argues, is another reminder that the United States has never truly subjected the presidency to the rule of law in foreign affairs.

The proper response, in his view, is to develop mechanisms, domestically and internationally, to hold future presidents accountable. Without such reforms, the next crisis will unfold much the same way.

“Manifestly illegal”: Philippe Sands on the danger of contagion

For Philippe Sands, professor of law at University College London and counsel in numerous cases before international courts, the abduction is an assault on the legal order itself.

“The action against Venezuela is manifestly illegal under international law, and cannot plausibly or by any reasonable standard be characterised as a law enforcement action,” he said.

The consequences, Sands warned, could be far‑reaching:

“One need only to think of Nicaragua, Afghanistan and Libya … to imagine what the consequences might be, and the encouragement it will surely give to others to act with such brazen disregard for the international legal norms that bind us all.”

More worrying, Sands observed, is the silence of allies such as Britain.

“Having lived through the catastrophe and criminality of the Iraq war in 2003, which Mr Trump himself has condemned, I would hope that Keir Starmer sticks to the principles of legality to which he says he is so firmly committed.”

The abduction, he added, is “a terrible precedent, one that opens the door to seizure of resources by other countries, and undermines the authority of the US in the world.”

Precedents and patterns

The alarm of these scholars is rooted in history. In December 1989, US forces invaded Panama and captured General Manuel Noriega, a sitting head of state who had been indicted in US courts for drug trafficking. Legal scholars criticised the operation then for ignoring the self‑defence requirement and for violating Panama’s sovereignty.

Washington claimed that Noriega’s trafficking and threats to American lives justified the invasion. Thirty‑five years later, it has dusted off similar justifications for Maduro’s seizure.

The pattern stretches back further. US interventions in Iran (1953), Guatemala (1954), Chile (1973) and Iraq (2003) all circumvented collective security norms.

The United States has repeatedly used humanitarian, anti‑drug or pro‑democracy rhetoric to justify unilateral action. Yet none of these rationales appear in the Charter’s limited exceptions to the prohibition on force.

A wider geopolitical play

The timing of the raid underscores its geopolitical dimension. Earlier in the week, Trump met Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and threatened to “knock [Iran] down” if it rebuilt its missile or nuclear programmes.

Within hours of Maduro’s abduction, Israeli politician Yair Lapid warned Tehran to “pay close attention to what is happening in Venezuela.”

Trump’s strategic doctrine, outlined in his 2025 National Security Strategy, resurrects the Monroe Doctrine in modern garb.

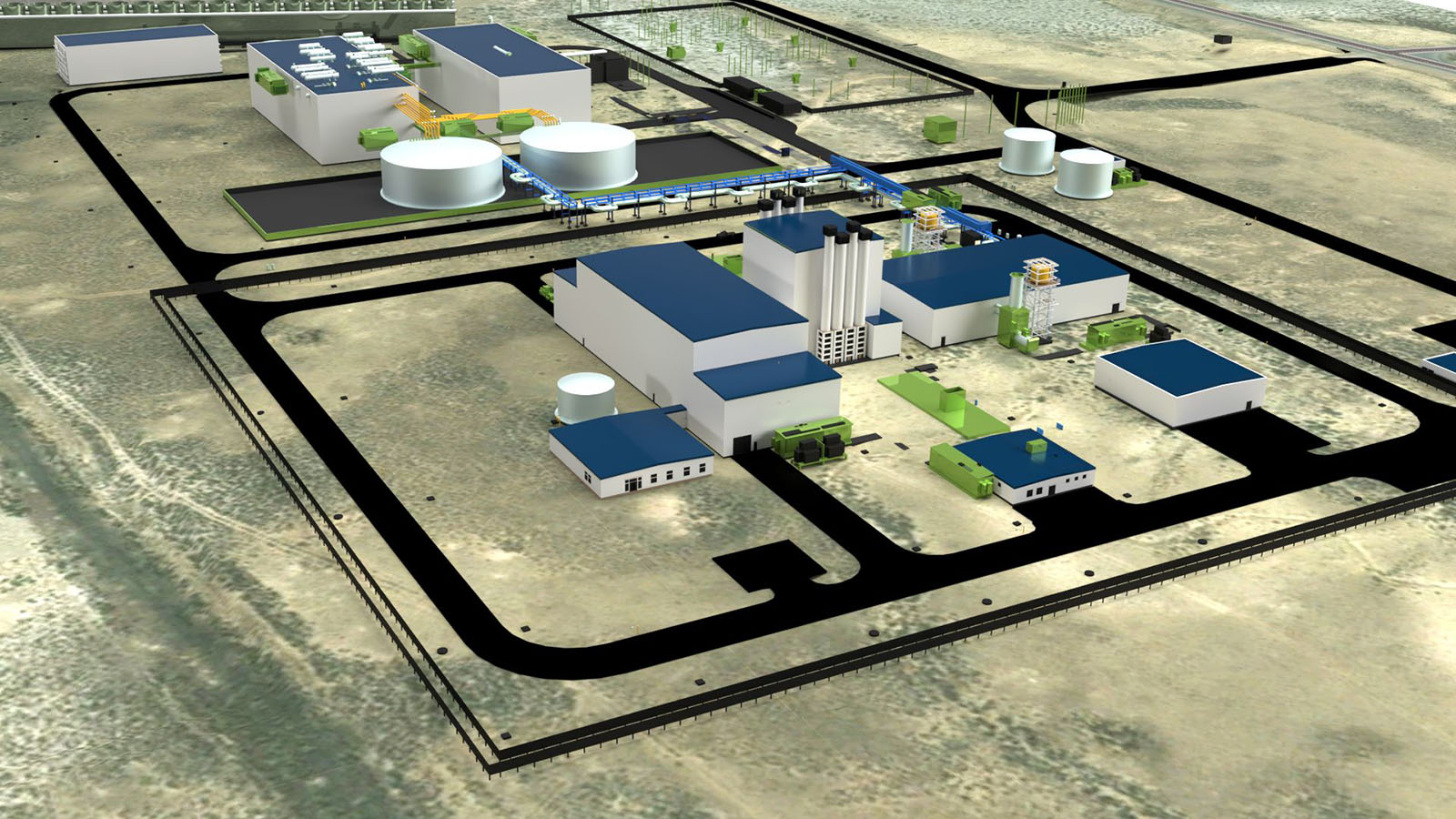

The document declares that, after years of neglect, the United States will “reassert and enforce” its dominance in the Western Hemisphere and that rival powers will be repelled. The attack on Venezuela, a major oil producer and ally of Iran and Russia, appears to be the first enforcement action.

Analysts worry that redeploying military resources to the Caribbean (aircraft carriers, destroyers, special operations forces) will overstretch the Pentagon at a moment when China’s military is expanding and tensions over Taiwan are rising.

The silence of allies and the future of the UN

Perhaps most striking has been the muted response from Washington’s traditional allies. Britain’s government, now led by Keir Starmer’s Labour Party, has largely avoided direct criticism. Sands laments that silence and urges adherence to the principles of legality.

Within the United States, Congress has also abdicated its constitutional role. Despite the Constitution’s requirement that war be declared by Congress, the legislature was neither consulted nor asked to authorise the operation. Some lawmakers muttered about the War Powers Resolution, but party loyalty and fear of appearing “soft” on drugs or immigration muted dissent.

The United Nations, too, has been largely paralysed. Any attempt by the Security Council to censure the United States would run into a US veto.

To sum up? The empire fights back

The seizure of Nicolás Maduro may be unique in its audacity, but it follows a century‑long pattern of American interventions that treat international rules as optional.

Alfred‑Maurice de Zayas calls it “international vandalism” and urges a global boycott of US arms and goods to reassert legal norms. Samuel Moyn reminds us that the episode is part of a long history of presidential impunity that will continue unless domestic laws change. Philippe Sands warns that the action is “manifestly illegal” and will embolden other powers to seize what they desire.

Whatever happens in the Manhattan courtroom, the precedent has been set. If the abduction of a head of state becomes the new normal, the prohibition on force in Article 2(4) and the very idea of sovereign equality may soon be consigned to history.

The United States, once the architect of the UN system, now appears to be presiding over its demise. For a world already beset by geopolitical rivalry, environmental crises and economic inequality, tearing up the rules of international order is an invitation to chaos.

The Maduro abduction is a test of which future we choose.

The latest news in your social feeds

Subscribe to our social media platforms to stay tuned