EXCLUSIVE: Capture the Tanker. Inside the US Oil Blockade of Venezuela.

There’s a new script for 21st-century coercion at sea: warrants, helicopters, Coast Guard boarding teams and civil-forfeiture filings. Over the last weeks, the US has moved from paper sanctions to physical interdiction – boarding and taking custody of tankers allegedly tied to Venezuela’s sanctioned oil economy. The names are now part of the geopolitical small talk: Skipper, Marinera, M Sophia, Centuries, Olina. What looked like sanctions enforcement has become, in effect, an oil blockade by other means – one that is mixing law, force and courtroom theatre in equal measure.

Call it Southern Spear. What started as stepped-up sanctions and intelligence work ripened into a coordinated multinational posture in the Caribbean: sustained naval rotations, amphibious assets on alert, and inter-agency teams rehearsing interceptions. Washington framed the effort as interdiction against illicit networks and “narco-terrorist” flows – but in practice the operation combined military presence with law-enforcement actions aimed squarely at choking revenue streams for Maduro’s government. SOUTHCOM has publicly described interdictions and maritime operations as part of that effort.

This was not a sudden brainstorm. Our previous reporting traced a gradual ramp-up: at-sea “shows of force,” strikes on suspected narco-boats, and a steady drumbeat of sanctions and asset freezes that narrowed the margins for vessels, brokers and insurers who had helped keep Venezuelan exports moving. Analysts tracking AIS tracks, satellite imagery and shipping records saw familiar patterns: tankers loitering near Venezuelan terminals, transponders switching off, rendezvous with lightering vessels and frequent changes of flag or ownership – the classic fingerprints of a “dark fleet.” That kind of behavior is what turned suspicion into operational targeting.

Operation Southern Spear also signaled a political decision: a willingness to accept diplomatic blow-back and legal risk to physically interdict maritime commerce. Seizing commercial VLCCs (Very Large Crude Carriers) is uncommon; it takes intelligence, legal scaffolding, and an appetite to carry the resulting fallout. In short: the US chose escalation.

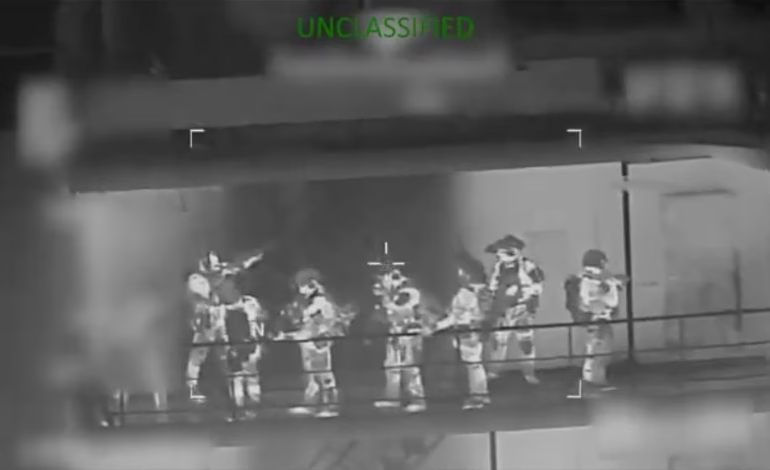

Here’s the short, gritty version: US teams identified suspect tankers, obtained warrants or legal grounds for boarding, approached under naval/Coast Guard cover, and put teams aboard – often using helicopters – to take control. In a number of cases, vessels were then escorted to custody to begin forfeiture proceedings. The public record and reporting give us a reasonable chronology.

In mid-December 2025 the tanker Skipper was intercepted off Venezuela, boarded by Coast Guard personnel and placed into US custody. US filings and reporting say the ship had loaded roughly 1.8 million barrels of heavy Merey crude and was linked through paperwork and communications to a sanctions-evasion network. Cuba and Venezuela blasted the move as “piracy”; Washington styled it as law-enforcement action.

The Marinera made headlines for a different reason – it was re-flagged to Russia, had a creaky ownership trail and was seized in the North Atlantic with reported UK assistance on intelligence. That seizure ratcheted up tensions with Moscow, because the ship’s registry and the optics suggested Russian protection for vessels moving suspicious cargo.

Reporting and open-source tracking flagged M Sophia and Centuries as stateless or dubiously registered tankers routinely operating in the so-called dark fleet. Those vessels were targeted in subsequent interdictions, their movement histories and AIS anomalies forming part of the evidence publicized by investigators.

On January 9, US authorities moved on Olina in Caribbean waters; Marine and Coast Guard teams boarded and the US initiated the process of seizing the vessel and any cargo aboard. Reuters reported the operation as the fifth such seizure in the campaign.

Two operational realities matter. First, many of the vessels had opaque flag histories, shell-company owners and evidence of transponder spoofing or AIS silence – practices that make it harder for regulators and insurers to follow the money and the crude. Second, the US leaned on a mixed legal toolbox: criminal warrants, civil forfeiture actions and claims of jurisdiction over “stateless” vessels to justify the boardings and seizures. Those distinctions – boarding versus seizure, visit versus confiscation – will matter a great deal in court.

The seizures didn’t just ruffle feathers in Caracas. They produced a predictable, and predictably loud, diplomatic backlash.

Moscow denounced the take-downs as illegal – or worse, as acts of piracy – and lodged formal protests. Chinese state and pro-government outlets framed the campaign as an assertion of hemispheric control and warned against US unilateralism. Western capitals have been more muted in public but active behind the scenes; reporting suggested the UK provided intelligence that aided at least one seizure, which fed Russian anger.

Legal commentators around the world chimed in with nuance and alarm. Under UNCLOS, states have a right to “visit” a vessel on the high seas to verify nationality; if a vessel is stateless the legal ground for action grows firmer. But boarding differs from seizure – and crossing that line to confiscate vessels or cargo under unilateral sanctions raises thorny questions about jurisdiction, due process and the extraterritorial reach of domestic statutes. Al Jazeera unpacked those legal debates, noting that US domestic law provides tools for seizure, while international law is less settled.

On the floor of the United Nations and in capitals, the incident forced an old script back on stage: power politics versus the rule of law. The practical response from Russia and China so far has been diplomatic posturing and legal denunciations rather than immediate naval countermeasures – but the rhetoric elevated the risk calculus.

Short answer: they change the game politically more than they vault global fuels markets.

Legally, expect litigation. The US has filed for warrants and civil measures to seize more than a handful of vessels; Reuters reported filings for dozens more. Each vessel’s fate is likely to be fought in US courts (for now), where the government will argue domestic statutory authority and factual evidence of sanctions-evasion; challengers will press jurisdictional limits and international law defenses. The result? Years of litigation, meanwhile leaving the seized ships and cargoes in legal limbo.

Overall expert opinion differs significantly. Allen S. Weiner, Senior Lecturer in Law and Director of Stanford Program in International and Comparative Law at Stanford Law School, underscores the lenses needed to examine these cases: domestic or international:

“As a matter of domestic law, although it depends a bit on the specific domestic statutory framework that the government is relying on, there are domestic statutes that permit the seizure of assets – and this would include oil tankers – that are involved in certain violations of US law.

As a matter of international law, if these are stateless vessels, and they are in international waters, it is permissible for a state to exercise its jurisdiction over them, at least to board and inspect them. There is disagreement among states and scholars about whether that right also permits the boarding state to seize the vessel. But the United States (and others) have long taken the view that this is permissible. The rules are different with flag vessels of another state or vessels in another state’s territorial waters. If you want to run that to ground, it might make more sense for us to do a call.”

Ian Ralby, President of Auxilium Worldwide and an expert in maritime and supply chain security warns about potential geopolitical implications:

“The legality of the seizure of oil tankers off Venezuela is not a cut and dry matter. In most cases so far, there has been a clear legal right to board the vessels, as most of them are either obviously without nationality (stateless) or have some sort of dubious registration history. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea in article 110 confers a right of visit (boarding) of vessels outside the 12 nautical mile territorial sea in order to confirm registration. So in every case, thus far, it is possible to find a legitimate legal right under international law for the Untied States to board the vessels. But there is a big difference between boarding and seizing. The seizures under unilateral sanctions by the United States have raised numerous questions of authority under both international law and national law in the US. Ultimately it will be for the courts to decide, based on the specific facts in each case, if the seizures were lawful. There are numerous procedural and jurisdictional questions, however, and time will tell how they will be resolved. From a policy standpoint, the United States has sanctioned numerous vessels, vessel owners and cargoes for years, but has not taken much action to enforce them. This lean forward on sanctions enforcement against Venezuela has also raised questions about whether the US will engage in similarly aggressive enforcement of sanctions against other states like Russia, Iran and North Korea. In the case of Russia, many of the sanctioned vessels are returning to the Russian registry now, as it seems that the Russian Federation is prepared to use national assets, including high end military assets, to protect the economic interests of moving sanctioned oil cargoes at sea. This could bring the United States or its partners – as the United Kingdom was a part of the recent seizure of the Marinera – into direct military confrontation with Russia. The implications of such an encounter are concerning for global security.”

Economically, the volumes tied up in the seizures matter to individual buyers and insurers but are limited relative to global flows. A few VLCCs contain meaningful crude for specific refineries, but they’re not a market-moving chunk world-wide. What matters more is the chilling effect: insurers and charterers become risk-averse; buyers in Asia (traditionally a big market for Venezuelan cargoes) see fewer reliable shipments; and the clandestine networks that previously moved crude face higher transaction costs and higher legal and operational risk. Reuters reported a projected drop in Chinese imports from Venezuela as the blockade tightened – not because barrels vanished from the planet, but because the freight lanes and insurance channels dried up.

Jean-Paul Rodrigue, Department of Maritime Business Administration Professor at Texas A&M University, Professor Emeritus at Hofstra University, places the current seizure in the macroeconomic and geopolitical context:

“A government seizing commercial ships is rather uncommon and usually involves an asymmetric seizure when it concerns a ship under the flag of a small nation such as Cuba or North Korea. For instance, in 2014, Panama seized a North Korean cargo ship carrying military hardware. However, the ship was eventually let go after a fine was paid.

The recent seizure of VLCCs (Very Large Crude Carriers) in the Caribbean is rather unprecedented since it concerns ships that are technically not carrying an official national flag, owned by a third party and acting on behalf of a sanctioned nation such as Russia, Cuba and Iran. Doing so requires a political will that few nations are willing to assume because of the complexity and the asymmetry of the situation. This means that only the United States, with a strong political will, could achieve such an outcome. Even in such a context, the international community was surprised by the seizures. China and Russia will be reluctant to intervene in a significant fashion because they are, at best, in a legal grey zone.

The economic outcome directly related to the seizures is limited. The oil has a commercial value, but not in quantities that could move markets. Since property is two-thirds possession, the confiscated ships could be sold to a shipping line or even US-flagged. It is at the macroeconomic and geopolitical level that things are moving. The US now appears to be reopening the Venezuelan oil market as a supplier, as Chinese and Russian geopolitical influence in the region wanes.”

Politically, the seizures are an attempt to shrink Maduro’s fiscal space and tilt the region. The US gamble is that denying revenue will either force internal concessions or accelerate a political realignment that opens Venezuelan resources to Western markets on US terms. The Department of Energy and allied policy shops have pitched the economic upside: bringing Venezuelan capacity back online as an alternative supply source, one that could bolster US leverage. But converting seized ships and contested crude into a long-term strategic asset requires legal wins, administrative steps and a political plan for post-seizure disposition. Expect court rulings, potential auctions, and long debates about where the proceeds – if any – will land.

There are limits. Experts note that Venezuelan fields need investment, wells require maintenance, and Merey crude is heavy and sour – often requiring specialized buyers and complex logistics. In short, reopening Venezuelan oil at scale is not an on/off switch. Even inside the US, proponents concede that the short-term impact on global pump prices is likely modest.

Mark Weisbrot, Co-Director of Center for Economic and Policy Research is adamant in his assessment and warns about potential international backlash:

“The Trump administration’s decision to seize oil tankers involved in the transport of oil to or from Venezuela is illegal. It therefore shows the whole world, not just countries directly impacted, that the US government does not respect the basic laws that allow for safe and peaceful international commerce.

It’s worse than that: the United Nations human rights office has stated that it’s a “prohibited use of military force.” The Trump administration claims that it is enforcing its own sanctions against Venezuela, but these sanctions are also illegal, as the UN and other experts on international law have stated. These sanctions, of which cutting off oil revenue was a major part, have devastated Venezuela’s economy, and led to tens or hundreds of thousands of deaths. The US Senate is currently considering a war powers resolution that would prohibit the involvement of the US military in hostilities in South America without authorization from Congress.”

Those seizures now look like a messy triangle of risk here: legal ambivalence, strategic gain and geopolitical hazard.

If you read the reporting and filings, the campaign looks like it has legs. Reuters and others reported that the US sought warrants to seize dozens more Venezuela-linked tankers – a sign the administration plans to follow the chain: well → ship → broker → buyer. That suggests a long game designed to narrow the avenues for sanctioned oil trade, forcing buyers either to stop taking Venezuelan crude or to accept political costs.

Operationally, expect more targeted interdictions aimed at vessels showing the classic dark-fleet behaviors: AIS gaps, frequent re-flagging, and suspicious lightering maneuvers. Expect also more civil suits and criminal referrals inside US courts – a legal broodmare of forfeiture cases, subpoenas and depositions that will keep the matter contentious for years. Analysts and think-tanks are already mapping the legal routes challengers will use, and policy shops are sketching contingency plans for market fallout.

On the market side, cargo flows will be reshuffled. Reuters reporting pointed to an expected drop in oil exports to China as a direct result of the blockade’s chilling effect; other buyers will either seek alternative suppliers, accept higher risk premiums, or use more clandestine, and costlier, logistics to move product. Insurers and banks will be watching closely; their retreat from risk could be the single most consequential economic effect.

And the diplomatic wild card remains Russia. If Moscow steps beyond words and deploys naval power to protect flagged ships – or if a miscalculated boarding causes casualties – the campaign could easily twist into a larger military confrontation. So far, the standoff has stayed in legal and rhetorical lanes, but with both sides testing limits, the margin for error is thin.

This is a new hybrid of coercion: the US has stitched together sanctions, intelligence, naval presence and aggressive law-fare to make moving Venezuelan crude riskier, costlier and legally perilous. The tactical effect – removing some cargoes and vessels – is important but not decisive; the strategic effect – shrinking options, scaring insurers and chilling buyers – is the real lever.

But the operation is no magic bullet. Reintegrating Venezuelan oil into global markets on terms favorable to Washington will require investment, legal clarity and time. And the campaign is not risk-free: courts could rule against the US in some cases, diplomatic pressure could deepen, and a single operational accident might spark a confrontation no one wants.

What we’re watching, then, is not just a set of maritime arrests. It’s an experiment in whether a major power can weaponize legal process, maritime policing and diplomatic pressure to rearrange the global energy chessboard — short of war, but resolutely not short of consequence.

The latest news in your social feeds

Subscribe to our social media platforms to stay tuned