EXCLUSIVE: Do Iranians Want a Shah? Who’s steering the story?

The flashpoint is obvious: angry crowds, brutal crackdowns, and a regime that looks shakier than it has in years. But beneath the headlines – the videos, the hashtags, the moral outrage, and the real-world carnage – sits a messier question: who do Iranians actually want to lead them? And is the idea of bringing back a Pahlavi monarch anything more than a media echo and a foreign-backed chorus?

This long read unpacks how we landed here, what’s happened since the unrest exploded, the rise (or re-rise) of exiled crown prince Reza Pahlavi as a symbol in some foreign coverage, the role (and limits) of Israel, the US, and other outside actors, and finally the sober guesses from regional experts about what comes next. I’ll use on-the-record reporting, timelines, and expert views – and list every source at the end so you can follow the thread yourself.

Start with the immediate spark: economic pain. In late 2025 Iran saw rapid currency devaluation, rising prices, and widened hardship for ordinary households and business owners. Street protests that began over bread and the cost of living quickly broadened into something more political – anger at the entire system, not a single policy. This wasn’t a single-city flare-up. By the time the unrest had spread, demonstrations were reported in almost every province, with wide demographic reach: students, workers, shopkeepers, truckers, and middle-class professionals turned out in various towns.

The state’s response was a defining feature: rapid internet shutdowns, mass arrests, and a degree of lethal force that human rights groups called catastrophic. Independent groups and activists reported thousands killed; organizations like Amnesty International described mass killings and demanded global diplomatic action to break the cycle of impunity. The regime answered with compressed trials and swift executions in some cases – actions that international media reported and foreign governments condemned.

Into this inferno came an American political environment that amplified the noise. High-profile US rhetoric – including threats of economic penalties and strong talk about “supporting protesters” – added fuel and confusion. In our previous coverage we warned that maximalist rhetoric from Washington risked raising expectations on the ground in Iran without offering any real protection, while also potentially hardening Tehran’s crackdown.

Meanwhile, analysis by Alex Vatanka, Senior Fellow at the Middle East Institute, painted a clear picture: the crisis grew from predictable political deadlock in Iran. Vatanka points to leadership failures, economic mismanagement, and a regime that has run out of credible political outlets for dissent. He described the regime’s structures – the Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), the Basij, and the security services – as intact and capable of brutal suppression, which keeps the balance of force, for now, in Tehran’s favor.

The last month pushed this crisis into a new – and darker – phase.

Iranian authorities announced thousands of detentions and claimed the protests were subsiding, while human rights organizations and exile networks warned that the scale of repression was enormous and that detention conditions were brutal. Timeline reporting makes clear that arrests ran into the low thousands and that internal communications were hampered by internet shutdowns.

Different actors tried to control the story of “who killed whom.” Domestic state media, diaspora networks, and international outlets published competing tallies and versions; investigators and groups outside Iran alleged mass casualty events in certain locations that Iranian authorities denied or attributed to chaos and clashes. That dispute over narrative is now its own battleground.

Leaders in Washington and elsewhere publicly criticized Tehran, applying economic pressure and moral condemnation. The US government made threats – tariffs and other moves were floated – while world bodies called for investigations into possible mass-atrocity crimes. But the risk of escalating to military or covert kinetic action was repeatedly flagged by analysts as unacceptably high.

A defining feature has been the protesters’ geographic spread and sociological diversity. Yet the movement has lacked a single, durable national leadership structure that can credibly threaten core pillars of the regime. In short: lots of anger, lots of boots in the streets – but not (yet) a unified political machine capable of displacing Iran’s security organs. Analysts warn that the state’s repressive capacity still gives it an edge.

If you’ve been monitoring Western media and social platforms, you’ve probably seen Reza Pahlavi’s face in the mix. The exiled crown prince – son of the deposed Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi – has used the discord to position himself as a possible alternative: pledging to reintegrate secular, pro-Western policies, promising to renounce nuclear ambitions, and even signaling a willingness to recognize Israel – a stance that earns him ardent support in some international circles and intense hostility inside Iran.

But here’s where the nuance matters:

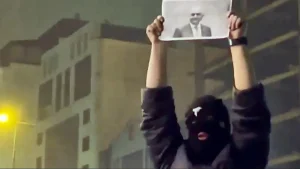

Inside Iran, support for a return of the monarchy is far from dominant. Surveys and on-the-ground voices collected by independent outlets show that while some protesters chant “no to the leader,” that does not necessarily translate into “yes to the Shah.” Many Iranians want reform, accountability, and an end to clerical rule – but they’re wary of foreign intervention, suspicious of exile figures, and divided on whether monarchy is the answer. Several commentators and scholars note that apparent pro-Pahlavi slogans caught on foreign feeds may be amplified by external actors, and the internet blackout made it easier for misleading clips – and deepfakes – to spread.

Reza’s messaging is designed for external audiences as much as internal ones. He publicly frames himself as a secular, democratic alternative and makes policy promises designed to reassure US, European and Israeli audiences (e.g., renouncing nuclear weapons and recognizing Israel). That resonates in Western media and with policy elites who prefer a clear, pro-West interlocutor. But that same alignment with foreign capitals – especially Israel – is politically toxic for many inside Iran, where foreign meddling is the regime’s favorite bogeyman.

Allegations of foreign amplification are credible and consequential. Al Jazeera’s reporting suggests networks with Israeli ties have actively pushed narratives in support of regime change and, in some cases, monarchist sentiment. That doesn’t mean all pro-Pahlavi content is fake or that no Iranians support him – it does mean the visible volume of “long live the Shah” content may be as much a function of external amplification as internal groundswell. That dynamic matters because Iran’s regime can point to outside influence to delegitimize homegrown dissent.

Israel’s role in this episode is delicate and instructive. Israeli policymakers are deeply hostile to the Tehran regime – for clear strategic reasons – but the public posture has been cautious. Analysts argue Israel wants to avoid direct, public involvement that could feed Tehran’s “foreign plot” narrative and consolidate internal support for the clerical leadership. Instead, reporting points to discreet intelligence contacts and back-channel consultations including with US counterparts, and to carefully calibrated efforts to shape messaging and options – not overt military engagement.

That caution is strategic: overt Israeli backing for a particular Iranian figure (like Pahlavi) or for aggressive kinetic options could backfire spectacularly inside Iran and across the region. The lesson: foreign governments can amplify, nudge, and exploit fractures – but when they’re seen as the authors of a movement, the movement’s legitimacy inside the country often collapses.

Experts are cautious:

Dr. Nader Hashemi, Director of the Alwaleed Center for Muslim-Christian Understanding and an Associate Professor of Middle East and Islamic Politics at the Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University, warns that Pahlavi’s apparent popularity is overstated and linked to his family’s resources and foreign backing. He reminds us regional autocrats are terrified because the social conditions that produced Iran’s unrest could arguably produce trouble elsewhere:

“The popularity of the baby Shah of Iran (Reza Pahlavi), who wants to restore the pro-Western dictatorship of his father, is greatly exaggerated. It is largely a function of his financial resources, which his family stole from Iran, and critically, his support from Israeli intelligence.

Other countries in the region are very worried about the mass popular uprising in Iran. All of the regional countries are dictatorships where a corrupt ruling elite rules over a disgruntled population that is suffering economically and politically. In other words, the social conditions that produced the revolt in Iran can easily produce a revolt in Jordan, Egypt, Algeria, Morocco, etc. Regional dictators fear they could be next.”

Dr. Kian Tajbakhsh, a scholar of Iranian politics and a full-time visiting professor at New York University, argues the surge in pro-Pahlavi rhetoric likely exaggerates actual monarchist support – a product of small internal monarchist activity amplified by external voices. He notes the protests are broad and geographically dispersed but haven’t broken the regime’s coercive institutions yet – and the regime’s brutal response keeps fence-sitters at home:

“Recent events – including the short but intense Israel–Iran confrontation – have demonstrated that Israeli intelligence penetration of Iran is deep and sophisticated, which makes it reasonable to assume that external actors are capable of amplifying or nudging certain narratives inside the country. That said, my assessment is that while there may be a relatively small number of monarchist supporters active inside Iran – some longstanding, others possibly newly mobilized – the visible surge in pro–Reza Pahlavi rhetoric likely overstates the breadth of that support. It is plausible that limited internal monarchist activity, combined with external amplification, has created the appearance of a larger and more cohesive movement than actually exists on the ground.

The immediate trigger for the current wave of protests appears to be rapid currency devaluation, which has sharply affected segments of the commercial and importing classes and then spread outward to other sectors of society. The protests are geographically dispersed and socially broad, which is significant, but they have not yet reached the scale or organizational coherence required to fracture the regime’s core institutions or overwhelm its repressive capacity. The state’s response has been swift and brutal, and this repression has had a predictable effect: it keeps millions of fence-sitters at home by sharply raising the perceived costs of participation. For now, the balance of power still favors the regime, even as underlying economic and political pressures continue to build.”

A more in-depth take on the political balance in Iran can be found in Dr. Tajbakhsh’s latest piece, ‘Size, Fear, Anger, Repression, and More: Key Factors to Watch in Iran,’ for The New Republic.

Yassamine Mather, editor of the Academic Journal Critique and a senior researcher at the University of Oxford, cautions that the US has refrained from direct military action for good reasons: the risk of regional conflagration, unclear military objectives, and the danger of consolidating the regime’s domestic support if strikes are seen as foreign aggression. She also flags how some pro-Pahlavi audio/visual material appears to be manipulated:

“The United States has so far refrained from direct military action against Iran during the 2026 protests due to a number of factors: strategic risks, unclear objectives, and significant pressure from regional partners. The main concerns are the high potential for triggering a major regional war, the absence of a defined and achievable military goal, and strong cautions from key Gulf allies. While countries like Saudi Arabia and Qatar urged restraint due to fears of economic and security fallout, and Turkey remained focused on its distinct regional interests, these allied positions formed part of the broader diplomatic context rather than the sole deciding factors. It was probably assessed that strikes could consolidate domestic support for the Iranian government.

There is no consensus that limited military action, for example assassination of the supreme leader, would be risk-free… Trump wants to avoid the kind of failed Carter-era rescue operations that he claims brought shame to the US. There were no cracks in the security and military forces (Revolutionary Guards). There were rumors that the US administration was talking to senior reformist figures, former president Rouhani and former foreign secretary Javad Zarif, and they were subsequently arrested, but it looks like this isn’t true.

On Reza Pahlavi, I think this is the result of a media echo chamber. He doesn’t have much support in Iran (even Trump knows that). Israel keeps promoting him, as he is a very close ally. Mossad and Israeli publicity media added fake audio to videos where Iranians were shouting “no to Rahbar (Khamenei) – no to Shah,” so that we heard “long live Shah.” We know these were fake audio because until the closure of the internet, Iranians were sending us the real ‘reels’ of the same protests, next to fake videos, telling us we did not use pro-Shah slogans.”

The balance of force remains tilted toward the regime in the short term. The protesters have demonstrated impressive reach and resilience, but they lack the unified organizational backbone to arrest the security apparatus’s machine. External actors can amplify and shape the story, but they can’t substitute for internal cohesion and mass, sustained civil disobedience that includes key institutions (certain military units, state bureaucracy, etc.).

So, do Iranians want the Shah back? Short answer: No – not as a majority.

Longer answer: The protesters’ palette is diverse. Some groups, especially monarchists in exile or small in-country cells, might cheer for a Pahlavi restoration. Other protesters explicitly want nothing to do with monarchy and fear a return to pre-1979 authoritarian cronyism. The majority seem to want a future where basic economic security, rule of law, and political accountability replace the clerical monopoly – but their preferred institutional forms vary: a secular republic, a constitutional democracy, or other hybrid arrangements are all on the table for different constituencies. Visible “pro-Shah” signals are real in pockets, but the weight of evidence suggests those signals are amplified and not universal.

Importantly, the regime’s favorite delegitimizing tactic – equating dissent to foreign conspiracy – works when exile figures become too visible. If pro-Pahlavi messaging continues to look like an externally pushed narrative, it risks pushing ordinary Iranians away from that option. History is messy: revolutions rarely produce neat, single-answer plebiscites on institutional choices while they are ongoing. Expect contestation, fog, and competing visions for some time.

Across all scenarios, foreign actors’ influence is a double-edged sword. External support that’s too visible risks validating Tehran’s repression. And for would-be exiles like Reza Pahlavi, the path from high-profile spokesman to plausible in-country leader is full of unknowns and domestic suspicion.

The Iran story is not a neat movie script. It’s a thousand micro-stories of hardship, bravery, misinformation, foreign strategy sessions, and brutal security calculus. Reza Pahlavi is part of the landscape – an exiled symbol who matters to some, but he’s not a magic wand. For real change to stick, it needs broad domestic roots, credible institutions, and, crucially, time. External actors can prod, punish, or photograph the moment, but the shape of Iran’s next political order will be decided mainly inside Iran – by Iranians who want something better than either clerical autocracy or foreign-orchestrated overthrow.

The latest news in your social feeds

Subscribe to our social media platforms to stay tuned