As Washington and Taipei deepen economic and technological ties through a major new semiconductor trade deal, Beijing is once again insisting that US arms sales to Taiwan amount to a fundamental rupture of the “status quo” in the Taiwan Strait. It is a familiar charge, and one that collapses quickly under legal and security scrutiny.

From an international law standpoint, China’s argument is weak. The Taiwan Relations Act, passed by the US Congress in 1979, explicitly obligates the United States to provide Taiwan with defensive weapons. That law remains the backbone of US policy. Bonnie Glaser, one of Washington’s leading foreign policy analysts, told the Wyoming Star:

“The Taiwan Relations Act, Passed by Congress in 1979, obligates the United States to sell defensive weapons to Taiwan. The United States does not recognize Taiwan as part of the PRC. US Army sales to Taiwan are not a violation of international law.”

That last point is critical. While the US acknowledges Beijing’s position that there is one China, it does not accept the People’s Republic of China’s claim of sovereignty over Taiwan. There is no international legal prohibition on arms transfers to Taiwan, and no treaty obligation binding Washington to Beijing’s interpretation of the issue.

If there is a party altering facts on the ground, Glaser argues, it is not the United States or Taiwan.

“The only country that is changing the status quo in the Taiwan Strait is the People’s Republic of China. They are using various means to coerce and threaten Taiwan.”

She points to a concrete and telling shift in military behavior. For two decades, from 1999 to 2019, Chinese military aircraft and vessels largely respected the informal median line in the Taiwan Strait. That restraint is gone.

“From 1999 to 2019, Chinese military ships and aircraft did not deliberately cross the center line in the Taiwan Strait, but they now do so almost daily.”

Against that backdrop, US arms sales look less like provocation and more like a response to a deteriorating security environment.

Deterrence, not escalation

Beijing often argues that weapons transfers to Taiwan increase the risk of miscalculation or accidental war. But that logic cuts the other way. Deterrence depends on capability and credibility, and the absence of either can be an invitation to force.

Glaser is blunt about how Chinese decision-making works in this context:

“If Taiwan has the ability to inflict high costs on an invading Chinese military (along with those imposed by US forces), than Chinese leaders might continue to rely on coercion and refrain from kinetic action against Taiwan.”

In other words, arms transfers make war less likely, not more. If Beijing never launches an invasion, the weapons never get used.

“If China doesn’t use force against Taiwan, they don’t have to worry about the weapons being used that Taiwan has procured. This is not a credible argument.”

The real escalation risk lies in a scenario where Taiwan appears militarily vulnerable and US resolve is uncertain — a combination that could tempt Chinese leaders to test the limits through force rather than coercion.

Strategic ambiguity still has life

Despite rising tensions, Glaser does not see the Taiwan issue as already lost to confrontation. Strategic ambiguity, the long-standing US policy of not explicitly stating whether it would militarily defend Taiwan, can still work, but only under specific conditions.

“I believe that the situation can still be managed through strategic ambiguity, But the United States must have credible military capabilities to defend Taiwan and the resolve to do so, if necessary.”

That credibility does not require a formal defense treaty or dramatic political declarations.

“We don’t need to have a treaty commitment or a political statement to convey US capabilities and resolve.”

What matters is whether Beijing believes the costs of force would be unacceptably high. Arms sales are one of the tools that help sustain that belief.

Trade, chips, and the strategic backdrop

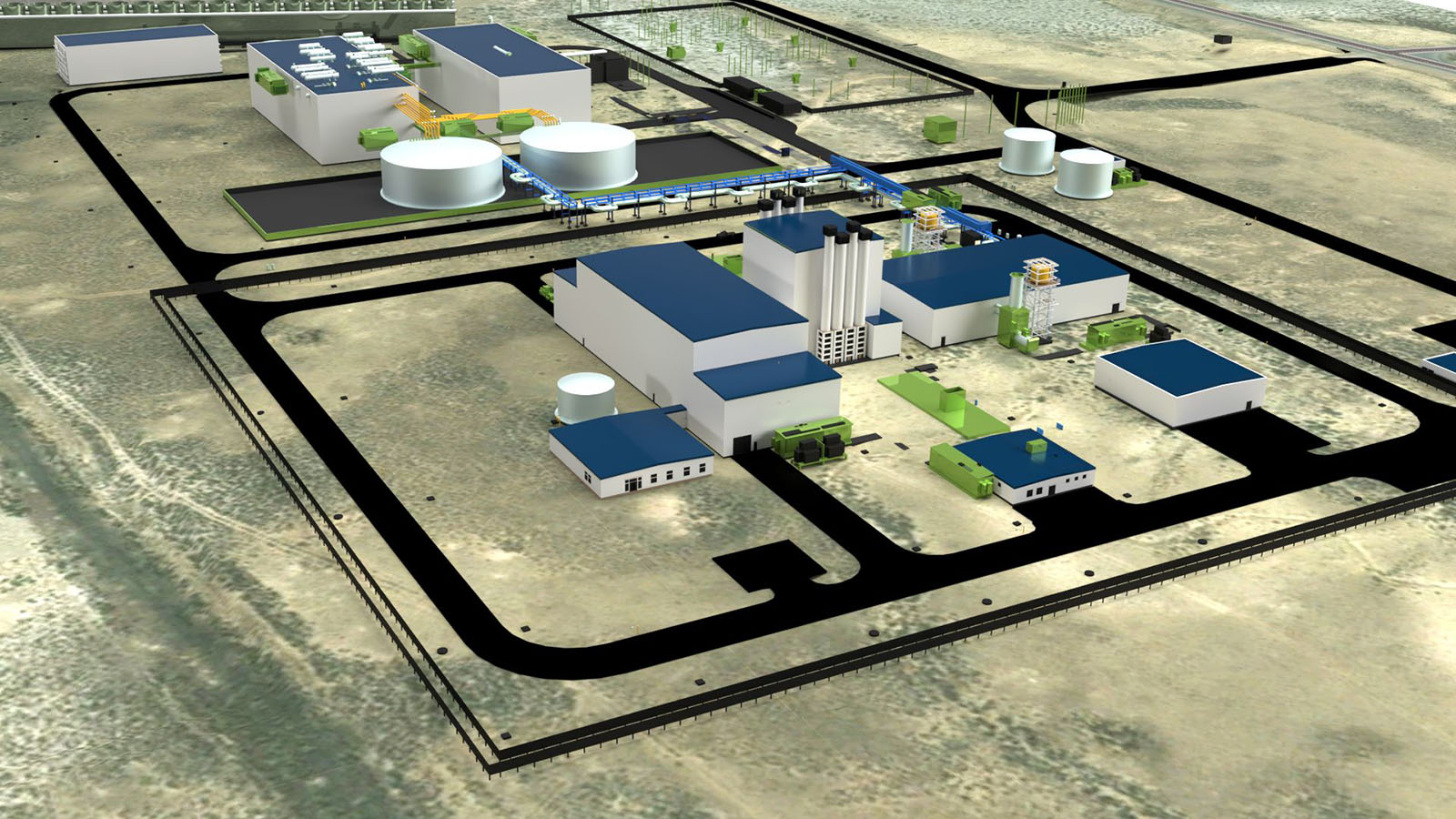

These security debates are now unfolding alongside a deepening economic alignment. The new US–Taiwan trade agreement centered on semiconductors lowers tariffs on Taiwanese exports and channels massive investment into American chip manufacturing. Taiwanese firms are committing at least $250 billion to US semiconductor, energy, and AI production, backed by another $250 billion in credit guarantees.

Officials in Taipei frame the deal as part of building a “democratic” high-tech supply chain with the US, not abandoning Taiwan’s role as a global chip hub, but reinforcing it through diversification. Preferential tariff treatment is also designed to blunt the impact of broader US semiconductor duties, while encouraging onshore manufacturing.

The latest news in your social feeds

Subscribe to our social media platforms to stay tuned