Greenland is not supposed to be the place where the Atlantic alliance unravels. It’s icy, sparsely populated, politically cautious, and for decades it has sat quietly inside a dense web of postwar agreements that worked precisely because nobody pushed them too hard. And yet, in early 2026, Greenland has become one of the most destabilizing symbols in Western politics – a place where history, security paranoia, trade coercion, and alliance fatigue collide.

This is not really a story about buying land. It’s about how pressure politics, applied clumsily, can fracture trust among allies faster than any external enemy ever could.

The idea of US control over Greenland is not new, nor is it particularly subtle. The United States has periodically eyed the island since the 19th century, when Secretary of State William Seward – fresh off the Alaska purchase – reportedly explored whether Greenland might also be acquired. That idea never went anywhere, but it set a precedent: Greenland as strategic real estate rather than a living society.

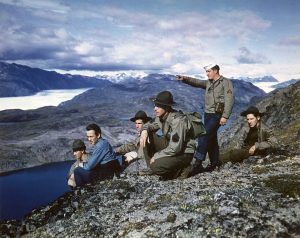

The logic sharpened during World War II. When Nazi Germany occupied Denmark in 1940, the US stepped in to defend Greenland, establishing military installations and effectively treating the island as part of the Western Hemisphere defense perimeter. That arrangement hardened during the Cold War, when Greenland became a critical node in early warning systems against Soviet missiles. The 1951 US–Denmark Defense Agreement formalized American military access, laying the legal foundation for bases such as Thule Air Base – now renamed Pituffik Space Base – which remains central to missile warning and space surveillance today.

What often gets lost in Washington’s rhetoric is Greenland’s political evolution. Greenland is part of the Kingdom of Denmark, but it has extensive self-rule and a strong sense of national identity. Since the introduction of home rule in 1979 and self-government in 2009, Greenlanders have taken control over domestic affairs and natural resources, with an explicit legal pathway toward independence should they choose it.

Modern coverage has repeatedly stressed this point, especially when US interest resurged during Donald Trump’s first presidency. When Trump publicly floated the idea of “buying” Greenland in 2019, the response from Copenhagen was disbelief, followed by anger. Greenlandic leaders were even more direct:

“Greenland is not for sale.”

That episode ended quickly, but it didn’t disappear. It became a reference point – a warning sign that Washington’s understanding of sovereignty and alliance norms was drifting.

Fast forward to 2026, and the old idea has returned with sharper edges. Our previous coverage described this moment as the “unravelling of multilateral restraint,” noting that Greenland has shifted from a symbolic curiosity to a test case for how far the US is willing to push allies when strategic impatience meets domestic political incentives.

The current phase of the Greenland crisis began not with tanks or treaties, but with rhetoric and leverage. The Trump administration framed Greenland as strategically vulnerable – allegedly exposed to Chinese and Russian encroachment – and suggested that existing arrangements were insufficient. From there, the argument slid quickly from “enhanced cooperation” to talk of acquisition, tariffs, and political pressure.

Crucially, the administration insisted it would not use force. Trump publicly ruled out military action and called for negotiations instead. That statement lowered the temperature – but it didn’t resolve the core issue: negotiations over what, exactly? Sovereignty? Access? Investment?

International reactions were swift and uneasy. Denmark reiterated that sovereignty and Greenlandic self-determination were non-negotiable. Greenlandic officials echoed that message while expressing deep skepticism about US intentions. NATO was pulled in almost immediately, with the Secretary General hosting Denmark’s defense minister and Greenland’s foreign minister at NATO headquarters – a clear signal that allies wanted to prevent the issue from metastasizing.

Media coverage captured the odd duality of the moment. On one hand, there was relief that Washington had stepped back from overt coercion. On the other, there was mistrust – especially in Greenland – about whether “deals” struck far away would respect local interests. Deutsche Welle reported that reactions on the island combined cautious optimism with lingering suspicion.

The Washington Post and The New Yorker were more blunt, framing the episode as a mix of historical ignorance and strategic overreach. The US, they noted, already has military access. What it lacks is patience – and that impatience risks alienating allies while delivering propaganda victories to adversaries.

The World Economic Forum in Davos became the moment when the Greenland dispute spilled fully into global politics. Trump’s speech there – emphasizing negotiation, denying any intent to use force, but doubling down on US strategic necessity – was designed to reassure markets and allies at once. It succeeded at neither completely.

Reuters described the effect as “whiplash diplomacy”: allies were forced to respond to rapidly shifting signals while trying to preserve unity on other fronts, including Ukraine. The result was confusion, frustration, and quiet recalibration across Europe.

Russia, unsurprisingly, welcomed the chaos. Le Monde highlighted how Moscow openly celebrated the dispute, portraying it as evidence of Western hypocrisy and division – a narrative tailor-made for Kremlin messaging.

Experts were unusually united in their criticism. Dr. Anders Wivel, Department of Political Science Professor at University of Copenhagen, emphasized that while the US has legitimate security interests in the Arctic, the red line for Denmark and Greenland is sovereignty and self-determination. He argued the most likely outcome is not annexation, but an updated security agreement that reflects new threats from Russia and China – potentially including greater NATO presence and guarantees related to rare earths and missile defense. Anything beyond that would be politically explosive.

“Greenland is part of the Kingdom of Denmark, but Denmark and Greenland are dependent on NATO and US support for the protection of Greenland. Denmark and Greenland recognize that the US has legitimate security interests in the Arctic, but the red line for Denmark and Greenland is the respect for territorial sovereignty and the right of the Greenlandic people to choose their own destiny. A 1951 agreement between Denmark and the US and close US-Danish cooperation during and after the Cold War secures that the US can scale their military presence up and down (after the Cold War the US has mostly scaled down). The most likely outcome of the current crisis in an updated security agreement that takes into account the security needs of the US, Denmark and Greenland and responds to the changing international order with a growing threat from Russia and China (bigger US presence, bigger NATO presence, some kind of guarantees to the US regarding rare earths, inclusion of Greenland in US missile defense) and this will maybe lead to some kind of US sovereignty over military base areas, but this might be more controversial in Greenland and Denmark.”

Dr. Marc Jacobsen, Associate Professor for Institute for Strategy and War Studies and Centre for Arctic Security Studies at Royal Danish Defence College, went further, accusing the administration of exaggerating threats to “securitize” Greenland and legitimize American control. He noted that there are no Chinese or Russian ships in Greenlandic waters, and that Arctic security has always depended on cooperation – not unilateral dominance. His historical reminder is striking: at its Cold War peak, US forces made up roughly 25% of Greenland’s population. The idea that Washington lacks access today simply doesn’t hold up.

“There are no Chinese and Russian ships in Greenlandic waters as President Trump claims. By exaggerating the threat and downplaying Denmark’s military contribution, he is trying to securitize the situation with the aim of legitimizing American control of Greenland.

The size of Greenland is equal to half of Western Europe so protecting and surveilling the whole country will have to be done together with close allies, just like Denmark and the US have done since the Second World War. Increasing NATO presence might be a possible next step in further enhancing security in the Arctic which is a geostratgeically important region… The US did have a significant military presence in Greenland during the Second World War and the Cold War… After the end of the Cold War, the US decided to decrease its military presence in Greenland because the USSR was no longer deemed an existential threat… In accordance with the Defence Agreement between the US and Denmark in 1951 – which was updated in 2004 with Greenland adding its signature – the US can today increase its military presence in Greenland.

The US president’s latest tariff threats clearly indicate that Donald Trump is more interested in the Greenlandic territory and its subsoil riches than in the security of the Arctic.

The US tariff threat toward EU countries that support Greenland’s right to self-determination is unlikely to have the effect President Trump hopes for. On the contrary, it unites EU countries even more in speaking out against US ambitions to take over Greenland while warning against a dangerous downward spiral across the Atlantic. This is no longer only about the future of Greenland. It’s about Europe’s support for the enforcement of international law, and it’s about setting a limit to how far the US can be allowed to go.

The tariff threats are a blow to the negotiation process of the high-level working group, but I don’t believe it is the end to it. It will be in the interest of Denmark and Greenland – and hopefully also the US – to continue on this diplomatic track where it’s about economy and security – not about territory which is a clear red line. Where we stand now, I see three elements that could become the result of the working group:

1) An updated defense agreement explicitly stating that Greenland could constitute an element in the Golden Dome project.

2) A promise not to allow neither Chinese nor Russian activities in Greenland in return for more US investments in realizing the country’s mining potential.

3) Further Danish investments in enhancing military presence in Greenland and the Arctic.”

More of Dr. Jacobsen’s analytics of the situation around Greenland can be found here.

Dr. James Goldgeier, Professor of International Relations and PhD program director at American University School of International Service, was unequivocal. A US attempt to seize Greenland by force, blatant imperialism against a NATO ally, would undermine the very norms the West claims to defend in Ukraine.

“A US effort to take over Greenland by force would be one of the most disastrous and consequential foreign policy decisions in American history. Prior to 1945, great powers routinely invaded and took territory from weaker countries. Our goal since World War II has been to try to prevent that. It’s why we formed an international coalition to force Saddam Hussein to withdraw his troops from Kuwait, which he sought to seize by military force. It’s why we’ve worked with our NATO allies to support Ukraine against a Russian takeover. Invading Greenland would be imperialism pure and simple, and against a NATO ally! The people of Greenland don’t want to be part of the United States. What would we do with them?

And we don’t need to occupy or annex Greenland. We have an agreement with Denmark dating back to 1951 that allows us the military access we need. We can fulfill our military and economic requirements without using military force against a NATO ally. The idea of adding Greenland is a pure vanity project of President Trump, who thinks adding territory to the United States would bring him glory. Instead, it would be disastrous for the country and for NATO, and thus a gift for Russian president Vladimir Putin.”

If Greenland is the symbol, tariffs are the weapon. When the administration threatened tariffs on European countries supporting Greenland’s right to self-determination, the move sent shockwaves through markets – not because they were inevitable, but because they were credible.

A state-by-state analysis later showed just how costly those tariffs would have been at home. When Trump canceled the threatened measures, 33 US states avoided $11 billion in additional costs. A Kiel Institute study found that 96% of tariff costs would have been borne by American businesses and consumers – not foreign exporters.

Between February and December 2026, US consumers would have absorbed nearly $27 billion in combined tariff costs, with states like Georgia, North Carolina, and New Jersey facing outsized exposure. Germany alone counts as a top-five import partner for 31 US states. These numbers map directly onto automotive, machinery, and industrial supply chains.

Reuters and The American Conservative both framed the tariff threat as leverage rather than policy – a pressure tactic designed to extract concessions without actually pulling the trigger.

Sam Bourgi, a finance analyst and researcher at InvestorsObserver, summed it up neatly: Greenland is not the prize – it’s the bargaining chip. Its value lies in Arctic shipping routes, critical minerals, and strategic basing. Sustained pressure, even without annexation, raises costs, delays investment, and injects volatility into North Atlantic markets.

“Economically, Greenland is best understood as leverage rather than a literal acquisition target. Its value lies in Arctic shipping routes, critical minerals, and strategic basing at a time when great-power competition is hardening (see President Trump’s desire to consolidate the Western hemisphere under US dominance). The Trump administration’s rhetoric appears less about purchasing territory and more about applying pressure where traditional tools, such as tariffs in early 2025, failed to deliver sufficient concessions. Greenland, in this context, becomes a mechanism to renegotiate trade, defense burdens, and Arctic access with European partners.

Europe’s ability to push back is limited by hard economic realities. Denmark lacks meaningful economic or military leverage over the United States, and broader European unity on the issue is likely to fracture once trade, defense spending, or market access are put on the table. A forced sale remains unrealistic, but sustained pressure would still impose tangible costs: higher insurance premiums and financing costs for Arctic infrastructure projects, delayed energy and mining investment in Greenland, and increased volatility across North Atlantic shipping and defense-linked equities.”

Dr. Gabriella Gricius, postdoctoral fellow at the university of Konstanz and senior fellow at the Arctic Institute, warned that this approach risks long-term damage. European states are reliant on US security guarantees, but they also have a legal and moral obligation to support Greenlandic self-determination. Using tariffs to force compliance doesn’t just strain trade – it challenges the foundations of the alliance itself.

“There is no basis for Trump’s justifications for purchasing Greenland. The US does have national security interests in Greenland, but everything it needs regarding missile defense and maritime monitoring of the GIUK gap, it gets through the current defense agreement between Greenland, Denmark, and the US and through the Pituffik Space Base. Justifications surrounding Russian and Chinese ships causing an imminent threat to Greenland are inaccurate. There are no ships or threat to the people of Greenland. There are Russian and Chinese ships exercising in the Bering Strait, on the opposite side of the United States.

While it seems as though tensions have calmed after Davos, it remains to be seen how discussions evolve. It poses a particular challenge for European powers, who are reliant on the US for their security guarantee but also have a moral and European obligation to support the self-determination of the people of Greenland. This incident has certainly caused a rupture within the transatlantic alliance. Although this was not necessarily a NATO matter, it has involved the Alliance as Denmark sees to expand the situation to not just purely a Denmark-US-Greenland matter but incorporate other European allies to make a case that for Trump, owning Greenland is not necessary for stronger US national security.”

A more in depth Dr. Gricius’ analytics can be found here.

The most likely outcome is not dramatic, but it is consequential: an updated defense agreement, more US and NATO presence, explicit limits on Chinese and Russian activity, and increased American investment in Greenland’s economy. All of that is plausible – and all of it can be achieved without touching sovereignty.

What has already happened, however, cannot be undone. Trust has been dented. The idea that allies can be coerced economically over territorial questions has been tested – and found destbilizing.

The latest news in your social feeds

Subscribe to our social media platforms to stay tuned