When Donald Trump stood in Davos this month and ratified a charter for a new “Board of Peace,” putting himself at the head of an international body meant to steer Gaza’s transition, a bunch of things happened at once. Headlines bloomed. Governments blinked. Aid agencies braced. And Palestinians on the ground wondered whether a slick plan drawn up in hotel conference rooms could survive the rubble, the politics, and a reality that has never been obedient to blueprints.

The Board of Peace is supposed to be the muscle behind Trump’s wider, 20-point Gaza peace plan: supervise a transitional technocratic administration in Gaza, coordinate billions in reconstruction cash, oversee demilitarization, and shepherd Gaza back toward some kind of Palestinian-run future. Sounds tidy. The problem is, the pieces it has to fit together are not. The political seams are raw, the humanitarian crisis is ongoing, and the very agencies the Board would sideline – the UN included – are warning that real life won’t be settled by ceremonial charters.

Below I unpack how we got here, what this Board is meant to do (and why many experts are skeptical), what the situation on the ground actually looks like, and what may come next.

The immediate backdrop is the brutal Gaza Genocide of 2023 onwards and the October 2025 ceasefire that the White House says was a first phase of a larger US-brokered plan. That ceasefire – achieved after intense diplomacy involving Egypt, Qatar, Turkey, and Washington – included hostage releases and a promise of phased Israeli withdrawals in exchange for Hamas concessions and a staged reconstruction program. Reporters and analysts called it fragile from day one.

Trump’s “Comprehensive Plan to End the Gaza Conflict“ – variously described as a 20- or 21-step blueprint – was published publicly and then folded into a UN Security Council resolution (2803) that welcomed the plan and the idea of a transitional governance arrangement for Gaza. The plan bundles three big moves:

- A ceasefire and hostage return;

- Demilitarization and a temporary technocratic administration for Gaza;

- Long-term statehood talks and reconstruction.

Whether those steps can be sequenced without sparking fresh violence is still profoundly uncertain.

Reporting from different outlets, be it the BBC, Reuters, or our own, has emphasized one constant: the first phase can be enforced with strong outside pressure, but the second – disarmament and the shape of governance – is where the plan tripwires. Hamas controls large swathes of Gaza and has little appetite for a unilateral arms surrender, the only thing keeping any hopes for national liberation; Israel’s political leadership is divided on how much Palestinian civil authority it will accept; and Arab and Western capitals have mixed appetite to commit boots, money or political capital.

The diplomatic “yes” on a paper plan does not erase the hard questions on the ground.

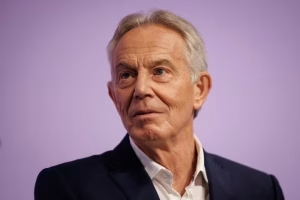

What the White House rolled out in Davos is both a governance proposal for Gaza and, perhaps ambitiously, an institutional prototype for other conflicts. The plan envisages Gaza administered temporarily by a technocratic Palestinian committee (local managers and experts running day-to-day services), under the oversight of an international transitional body – the Board of Peace – chaired by Trump and including a roster of heads of state and former officials (Tony Blair‘s name is floating around). The Board would set funding rules, vet projects, authorize reconstruction contracts, and, critically, determine when – and if – the Palestinian Authority is ready to resume control.

That’s a lot of power to vest in a single entity – especially one that critics say is personality-driven, top-down, and answerable to a small group of self-selected states rather than the multilateral UN machinery. The White House argues the Board is needed because the UN system has been compromised or slow; critics answer that sidelining established institutions risks duplicating effort, politicizing reconstruction funds, and undermining the legal frameworks that protect civilians and refugees.

Experts are skeptical in different ways:

Gregory Aftandilian, Senior Professorial Lecturer at the School of International Service at American University and adjunct faculty member at Boston University, notes the Board started as a narrow, technocratic idea to run Gaza’s services, but “morphed into something much broader.” He warns leading European states have mostly stayed away because they see it as a Trump-centric power play and question long-term accountability; he also flags that disarming Hamas is anything but straightforward and that few countries want to join a stabilization force that may have to confront militants:

“Trump’s Board of Peace, as initially outlined in his 20-point peace plan for Gaza, was to oversee a temporary administration of Gaza made up largely of Palestinian technocrats. It was also designed to handle the funding for the reconstruction of that area. However, since the 20-point plan was announced, the Board of Peace has morphed into something much broader, potentially being a rival to the UN, and to possibly deal with other conflict areas. Many leaders of countries who ave joined this Board have done so to either ingratiate themselves with President Trump or to stay in his good graces. However, major European countries have stayed away from it, in part because they see it as another power grab by Trump who would presumably remain its chairman even after he leaves the US presidency.

As for the next steps in the Gaza peace process, they are likely to be highly problematic. Hamas, which controls about half of the Gaza Strip, is supposed to be disarmed but it is doubtful it will give up its weapons voluntarily. This is why very few countries have signed up to join the International Stabilization Force for Gaza–they do not want to be in a position of forcefully engaging with Hamas. All this portends another round of fighting between Israel and Hamas, which Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu probably sees as being in his own political interest, as it would placate his far right cabinet members and delay the holding of new parliamentary elections.”

David Mednicoff, Associate Professor of Middle Eastern Studies and Public Policy at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst, Fellow at the Middle East Initiative at the Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, points out the “devil is in the details”: will the Board be a venue for business deals and influence-peddling, or a transparent body run by civil-servant experts? He raises the concern – widely voiced – that the Board currently looks too friendly to investors and political heavyweights, and too little like an institutional builder for Palestinian self-determination:

“The prospects that the Board of Peace might be useful in Gaza are a classic case of the devil being in the details.

Because President Trump tends to use his international connections to gain business for himself, his family and friends, and because he does not seem concerned about global democracy or international law, there is a strong possibility that the new international body will mostly be a place for the President to strut around the world stage, rather than a well-designed institute to reconstruct a peaceful and prosperous Gaza primarily for the benefit of the Palestinians, who have called it home for many decades. That the US government has violated international law in its recent military actions in Iran and Venezuela, pulled out of a variety of international treaties and organizations recently, and shown frequent expressions of disdain for the United Nations, certainly all point in the direction that the Board of Peace is mainly a vanity project for the President.

On the other hand, President Trump thrives on unpredictability, and has shown some willingness to push back against the wishes of Israeli government officials, including Prime Minister Netanyahu, who have shown little interest in Palestinian prosperity or stable self-governance. Moreover, the idea of collecting large sums of money to provide funding for reconstruction is critical to prospects for a Gaza that can thrive for Palestinians.

Like most specialists on international law or the Middle East, I am generally rather skeptical about the Board of Peace, with its preference for real-estate moguls and authoritarian leaders over experts and supporters of democracy. However, I would be happy to be proven wrong and to say this new organization actually lead to new and improved conditions for Palestinians and Israelis alike, and a path to Palestinian self-determination.”

Stephen Zunes, Professor of Politics and International Studies at the University of San Francisco and longtime analyst of US policy and nonviolent movements, is as blunt as always: the charter centralizes power in Trump’s hands in ways that look aimed at undermining the UN system. He calls the membership skewed toward authoritarian or far-right leaders and warns that the board’s governance rules – including Trump’s authority to name and remove members and to set agendas – make it unlikely to attract broad legitimacy:

“The United Nations was willing to initially give support to the formation of the Board of Peace when it was seen as the best way to maintain the shaky ceasefire in Gaza, but the subsequently released charter doesn’t even mention Gaza. Indeed, it appears to be an effort to undermine the United Nations system as a whole.

Trump has given himself effective control of the direction the board takes and the sole authority to name members, terminate members, and choose his successor. He can decide when the board meets and what it discusses, as well as issue resolutions without the approval of other members. Given that Trump’s credibility in the international community is at an all-time low, it is extremely doubtful that more than a couple dozen nations will take part. It doesn’t help that a disproportionate number of leaders who have joined or have expressed interest are far right and/or authoritarian. Indeed, two of the invited members, Benjamin Netanyahu and Vladimir Putin, were unable to attend the signing ceremony in Switzerland because they would be arrested as indicted war criminals. Furthermore, Trump’s insistence that nations pay him one billion dollars to join, particularly since he can remove them at his whim, makes it look like some kind of scam.

As a result, it is hard to imagine it will be more than a historical footnote.”

There are operational problems too. The Board’s plan presupposes:

- A functioning set of monitors to verify demilitarization;

- A list of donor states willing to write multi-billion-dollar checks;

- An international stabilization force willing to take risks;

- An administrative structure that works in a densely populated, politically fraught place like Gaza.

None of those are easy. Public statements by some governments, including several European capitals and a handful of US allies, have either declined to join or flagged legal and ethical concerns. Even states that do join may be reluctant to put troops on the line.

Will it work? Maybe, if (and it’s a very big if) the Board can convert political theater into durable multilateral commitments, bring in neutral experts, and convince both Palestinians and Israelis that its role is temporary and accountable. If it instead becomes a conduit for top-down investment deals or a protectorate-style manager that sidelines Palestinian voices, it risks inflaming grievances and creating parallel authority rather than solving governance gaps. Experts all emphasize the same thing in different words: legitimacy matters.

If the Board’s arguments rest on the need to rebuild Gaza, the facts on the ground are the why. Gaza’s infrastructure is shattered after years of intense conflict; hospitals, schools and water systems are barely functional; and winter months have sharpened the desperation of civilians. Independent reports and UN agencies say that even modest reconstruction will cost many billions and take years. Humanitarian access remains fragile and uneven, despite the ceasefire.

Then came another blow: Israel recently demolished buildings at the UNRWA (the UN agency for Palestinian refugees) compound in East Jerusalem – an action that drew immediate condemnations from Western foreign ministries, UN officials, and rights bodies. The demolitions intensified worry among aid planners that critical partners and assets are being weakened at the very time Gaza needs the whole international humanitarian system intact. UN officials and many donor countries called the demolition an unprecedented strike against the UN system.

Humanitarian responders – including the ICRC (International Committee of the Red Cross) – warn that access is still the bottleneck.

The ICRC spokesperson said that even after 4 months into the ceasefire, aid flows and distribution are inconsistent, shelter and medical shortages persist, and thousands remain unrecovered or missing. The ICRC stresses that governance debates over Board structures are secondary to getting life-saving assistance to civilians now:

“More than 100 days into the ceasefire agreement, we have yet to achieve the necessary unhindered flow of assistance and reliable distribution in Gaza. While conditions have marginally improved for the civilian population, they continue to face death, destruction and shortages in medicine, shelter items and other basic services, particularly during the winter season. Thousands of people remain missing amid limited resources to either recover human remains or facilitate identification.

Our appeal to the parties is for the situation for civilians on the ground to be urgently improved, for humanitarian aid to reach those in need, and for lives to be protected, regardless of political structures or initiatives.

As a neutral, impartial, and independent organization, the ICRC does not speak on politics, but instead focuses on providing effective humanitarian response. Right now, the ICRC is focused on the flow of humanitarian assistance and the ability of humanitarian actors to operate across the Gaza Strip.

The future governance of Gaza and related mechanisms are the responsibility of states and the Palestinian people – not the ICRC. It is imperative, however, that parties respect international humanitarian law.”

Palestinian advocates and civil-society groups are going further. Riham Jafari, Communication and Advocacy coordinator for ActionAid Palestine, told Wyoming Star:

“Without recognizing justice, international law, or Palestinian rights, lasting stability to Gaza can’t be achieved. Peace for Palestinians in Gaza must mean an end to violence, unrestricted humanitarian access, and protection of civilians not political declarations. Peace can’t be achieved without upholding international humanitarian law and the right of Palestinians to live in freedom and dignity.

Declaring the Board of Peace is a hollow gesture while collective punishment, displacement, and impunity continue in Gaza. Lasting peace in Gaza and the occupied Palestinian territories requires inclusive political solutions rooted in justice, accountability, and respect for Palestinian self-determination.

If Boards and structures of peace are not based on UN bodies and principles, they are another forms for occupation and alternative ways for sidelining existing UN bodies. There is no mention of Palestine, the Gaza Strip, or the Palestinian people. The right to self-determination and return is entirely absent. No Palestinian representative has been invited.”

In other words, rebuild without rights and you rebuild the grievance machine too. That concern explains why many Palestinian voices have been alarmed that the Board’s charter and the Davos presentations did not center Palestinian representation.

Put these pieces together and you see why reconstruction money – even if it flowed – might not land where it needs to. UNRWA and the broader UN coordination system are vital distribution platforms with long-standing ties to local communities; weakening them complicates relief and erodes trust. Meanwhile, the demolition of UN premises in East Jerusalem has reinforced fears about the erosion of legal protections for Palestinian institutions.

Nobody expects a tidy conclusion. But here are three rough scenarios that feel plausible in the months ahead:

1) Managed transition with heavy international oversight (best-case, narrow):

If the Board can attract trusted, resource-rich partners, create a transparent reconstruction fund, and bind Israel, Egypt, Qatar and donor states to clear rules on demilitarization, then a technocratic administration could stabilize basic services and rebuild neighborhoods. This requires buy-in from Palestinian political actors (including intra-Palestinian compromise), ironclad humanitarian access guarantees, and credible, impartial monitors for decommissioning weapons. Small but meaningful progress could then be parlayed into talks about Palestinian governance.

2) Stalled transition and creeping partial control (the likely muddle):

The Board struggles to build legitimacy; funding arrives in fits and starts; Hamas and other Palestinian groups resist full disarmament; Israel maintains pressure and occasional operations; and reconstruction projects become politicized. Aid is provided – but unevenly – and Gaza’s recovery is balkanized into projects that favor investor-friendly zones and leave large swathes neglected. This outcome risks embedding a new status quo: a semi-administered Gaza with weak Palestinian sovereignty and periodic violence. Experts warn this is the path to long-term instability.

3) Renewal of conflict (worst-case):

If demilitarization efforts fail, if the Board’s moves are perceived as occupation-lite, or if reconstruction becomes a vehicle for dispossession, then the cycle of armed confrontation could resume. That may suit some hardline political actors on all sides who benefit politically from fear and division. Multiple analysts caution this is not a theoretical risk: the sequencing of ceasefire, withdrawal, and disarmament is historically where deals have broken down.

The Board of Peace promises a simple story: outside expertise and money plus a neutral technocratic administration equals Gaza rebuilt. That’s a seductive narrative – especially for donors tired of endless conflict. But rebuilding cities is as much a political project as an engineering one. Without clear accountability, Palestinian participation, respect for international law, and durable security guarantees, even bold investment plans can create new problems faster than they solve old ones.

If the Board is serious about helping Gaza, it must do three things first:

- Secure a genuinely multilateral funding mechanism with transparent governance and independent auditing;

- Ensure humanitarian agencies like UNRWA are protected and integrated (not sidelined);

- Create an enforceable, verifiable pathway for disarmament that minimizes the risk of armed confrontation and avoids forcing Palestinian political identities into premature exile.

Failure on any of these fronts risks converting a ceasefire into a costly episode of international theater.

The Board of Peace could, at best, be a bridge – if built with bricks of legitimacy, not spotlight. At worst, it may be remembered as a short-lived institutional experiment that never fully squared the messy arithmetic of rights, recovery and real politics in Gaza. For the people caught in its calculus, however, words and charters are a poor currency; they need water, medicine, roofs, schools and the legal right to a future. That’s where the next test will be measured: in delivery, not declarations.

The latest news in your social feeds

Subscribe to our social media platforms to stay tuned