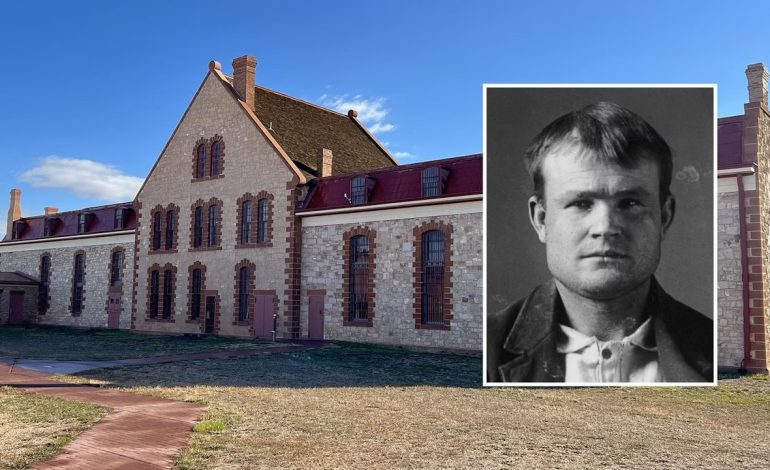

The only time Butch Cassidy was ever locked up, he served 18 months in the Wyoming Territorial Prison in Laramie. Far from being reformed, the experience hardened him. According to family accounts, he vowed that if he was going to be treated like an outlaw, “he would show them what an outlaw was.”

Cassidy—born Robert LeRoy Parker—arrived in Wyoming in 1890 as a working cowboy, well-liked in Dubois and Lander. His trouble began when he bought stolen horses from a man named Billy Nutcher. During the so-called Great Western Horse Thief War, Cassidy was captured after a brief gunfight and brought to Lander to face trial.

The prosecuting attorney was his friend William L. Simpson. Despite Cassidy’s claim that he had a bill of sale, a jury convicted him of horse theft and grand larceny. He was sentenced to two years in the penitentiary.

The night before he was to report to prison, the jailer let him go to Lander to settle his affairs. Cassidy promised to return by dawn—and did. Sheriff Charlie Stough later transported him to Laramie without handcuffs, trusting his word. When the warden expressed horror, Cassidy reportedly shrugged: “Honor among thieves, I guess.”

He arrived in July 1894 as inmate No. 1897, claiming to be George Cassidy from New York to protect his Utah family. He was 27, five-foot-nine, with blue eyes and a fresh scar from his capture.

The prison operated under the Auburn system: strict silence, striped uniforms, lockstep walking. Prisoners were referred to by number, not name. Cells measured six feet by six feet, stacked three high. Cassidy moved every few weeks to prevent familiarity—about 36 cells during his stay.

Prisoners worked 10-hour days to offset costs. Cassidy likely helped in the kitchen or with horses, though records are sparse. He was a model inmate, earning better cells: warmer on the third level in winter, cooler on the lower level in summer.

Eighteen months later, Governor Brooks Richards pardoned him on the recommendation of the very judge who sentenced him. “I do not doubt but that he would be capable of organizing and leading a lot of desperate men to desperate deeds,” Judge Jesse Knight wrote—hoping Cassidy would choose the straight path.

He did not.

By August 1896, Cassidy was linked to the Bank of Montpelier robbery in Idaho. His sister Lula later said prison had embittered him. “He said if they wanted to treat him as an outlaw, he would show them what an outlaw was.”

For the next four years, he did exactly that.

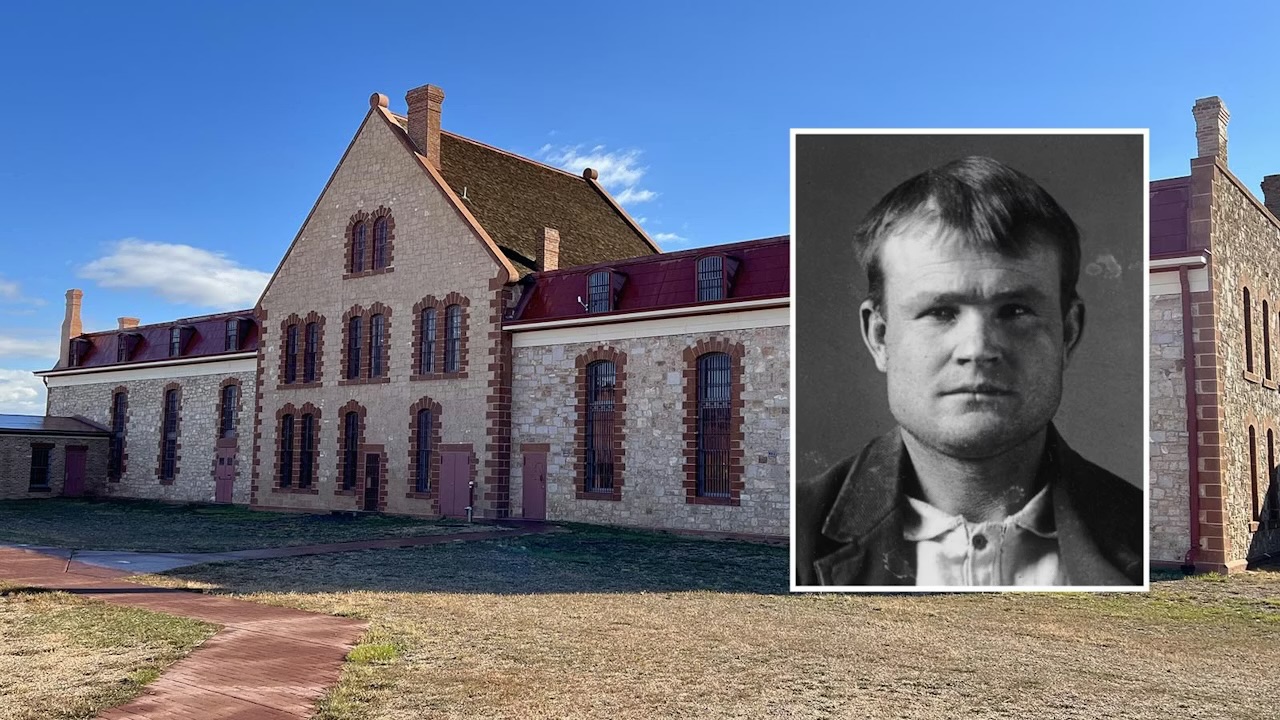

The Wyoming Territorial Prison, which operated from 1872 to 1903, is now a museum. Visitors can walk the cells that held Cassidy and more than a thousand other inmates. “This prison helped tame the Wild West,” said Lynette Nelson of the historic site.

In Cassidy’s case, it also helped create one of its most enduring legends.

The latest news in your social feeds

Subscribe to our social media platforms to stay tuned