Unusual Summer Elk Deaths Raise CWD Red Flags at Key Wyoming Feedground

A handful of mysterious summer elk deaths has wildlife managers on edge as western Wyoming heads into what could be a make-or-break winter for one of its feedground-dependent herds, Oil City News reports.

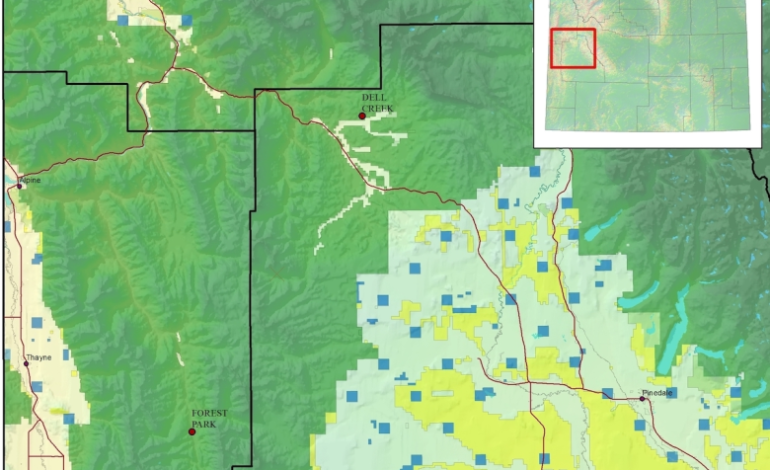

Last spring, after snow finally pulled back from the Hoback Basin, about 480 elk drifted away from the Dell Creek Feedground north of Bondurant, spreading out toward high-country summer ranges in the Gros Ventre Range and beyond.

Most of those animals disappeared into the landscape, as they always do. But 14 adult cow elk were wearing GPS collars — and what happened next got biologists’ attention.

Over the summer, three of those 14 collared cows died in the high country. That’s more than 20% of the tracked animals, and it’s unusual: healthy cow elk can live into their 20s and rarely die in summer, the safest season of the year for adults.

Wildlife managers tried to reach the carcasses quickly, but they were too late.

“Although they reached the carcasses within a couple of days of the mortality signal, the carcasses had been completely scavenged, and no samples were available,” Wyoming Game and Fish Department staff wrote in an emailed response.

That meant a critical question went unanswered: Did those elk have chronic wasting disease?

Those summer deaths didn’t happen in a vacuum. Chronic wasting disease (CWD) — a fatal, degenerative prion disease affecting deer, elk and moose — was confirmed in elk at Dell Creek for the first time last winter.

During the 2024–25 feeding season, Game and Fish found six CWD-positive elk dead in or right next to the Dell Creek Feedground, which operates on Bridger-Teton National Forest land. That’s about 1.3% of the elk counted on the feedground at the time.

But that number is almost certainly the tip of the iceberg.

Because elk can survive with CWD for years before showing obvious symptoms, the true proportion of infected animals is likely several times higher, said Hank Edwards, former supervisor of the Game and Fish Wildlife Health Lab.

“Given how long elk can live with the disease, your minimum prevalence is going to be four times [higher than 1.3%],” Edwards said. “It’s closer to 5%, probably.”

On its own, 5% CWD prevalence in an elk herd isn’t catastrophic. Statewide, about 3% of elk tested positive last year, and some herds have lived with low levels of the disease for decades.

What worries biologists is where the trend is headed — especially on feedgrounds, where elk pack tightly together for months, sharing the same ground, hay and saliva. Those are ideal conditions for a disease that spreads through bodily fluids and can persist in soil for years.

CWD has already hammered some Wyoming mule deer herds, shrinking populations and hunting opportunities. Many fear elk that rely on feedgrounds like Dell Creek could be on a similar path if infection rates spike.

“This next year could be really interesting,” Edwards said. “It’ll hopefully provide some clues.”

He called the coming winter at Dell Creek “so important” for understanding what’s coming next.

There is at least one encouraging data point: so far, hunter-submitted samples from the areas around Dell Creek show very few positives.

According to Game and Fish:

- In Elk Hunt Area 84, 0 out of 151 samples have tested positive.

- In Hunt Area 87, just 1 of 33 samples — an elk taken by a hunter this fall — has tested positive.

That doesn’t mean the herd is in the clear, but it suggests CWD is still in its earlier stages in the broader population.

At the same time, the agency is stepping up its efforts to track and understand the disease:

- Staff are exploring a newer test called RT-QuIC, which can detect tiny amounts of CWD prions, even from live-animal tissue.

- They’ve collected soil and fecal samples for future testing.

- More elk will be fitted with GPS collars during this winter’s feeding season to better follow survival and movement.

Despite rising concern, there are no current plans to change how Dell Creek is run this winter.

Wyoming’s elk feedground management plan only allows feedground changes after a lengthy, consensus-based process. The state is working through its six “feedground-dependent” elk herds two at a time.

Right now, the focus is on the Jackson and Pinedale herds. Their specific feedground plans are being reviewed by stakeholders, with public review still to come.

Dell Creek — part of the Upper Green River Herd — won’t be formally addressed until that herd’s planning process starts, which could be years away.

By then, managers will have far more data — and likely far more CWD — to work with.

For now, Dell Creek’s elk will return to their familiar 35-acre patch of hay-strewn ground in the Hoback Basin. And over the next four months, biologists will be watching closely to see whether this winter is just an early warning — or the start of a much steeper slide.

The latest news in your social feeds

Subscribe to our social media platforms to stay tuned